Place of Refuge – Part One

The numbers of people who have been forced to leave their homes throughout the world are staggering and growing—imagine the entire population of the United Kingdom or half the population of Mexico having to leave their homeland. How do we begin to understand what that means? While the scope of this global crisis may seem incomprehensible and the solutions beyond our reach, at the heart of the crisis are individuals trying to survive to keep their families together, and to find safe landing. In this seven-part series, we look at the stories of those who have sought refuge and those who have entered into their lives to offer help and support.

This story is Part-one of the Place of Refuge series.

Click Here to View Additional Stories >>

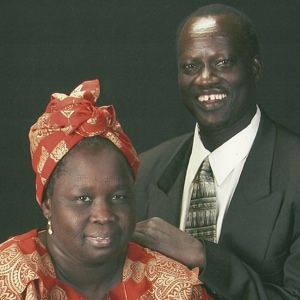

Covenant pastor and missionary James Tang was forced from his home in southern Sudan thirty-six years ago, and spent the following twelve years seeking refuge from civil conflict and persecution. Rooted in the complexities of colonial rule, ethnic tensions, and political divisions, his story provides a window into the challenges of survival, of keeping family together, and trying to find sanctuary from the threats of violence that continue today.

Since Sudan gained its independence from the British in 1956, national politics in my country have been marked by Muslim sectarianism in the north, weakened political organization in the south, widespread dissatisfaction in the relatively underdeveloped east and west, and failure to reach an agreement on the form of the constitution to govern our country.

In 1982 I was working as an evangelist and choir leader in my hometown of Ulang in Southern Sudan. One day a military captain invaded two nearby villages. His troops captured civilians, including some of my colleagues, and brought them to our town. They tied them up to trees, tortured them, and killed some of them. After witnessing that atrocity, I joined protests against the army and its brutal actions.

As a result, even though I was a church worker with influence in the community, I was placed on a most wanted list. The government kept watch on me in all my activities and tried to arrest me when I was teaching members of the church. For five years they banned me from traveling outside the city.

In 1984 I married my wife, Rachel. We became pregnant. But we had no access to medical care, and our child died within seven days of being born. Our second pregnancy ended the same way. When Rachel became pregnant a third time, a friend advised me to find medical help for her. So I sold all of our belongings for $1,500 to take her north via Malakal City, where she could access medical treatment.

The only way to get to Malakal was on a military con-voy, so I asked my pastor to write a letter to the military commander requesting their help. They accepted our request, and in March 1987, Rachel, my mother-in-law, and my nephew, who also needed medical treatment, and I boarded military vehicles to Malakal. We had gath-ered some local tobacco and other items to sell when we got there, which we loaded onto the vehicles. But two miles outside of town, they stopped the convoy, and the commander told Rachel to get out. They had decided that at eight months pregnant she was a liability. They feared she would go into labor if rebels attacked the convoy. When I realized what was happening, I asked them to unload my belongings. But they refused and drove away, leaving us empty-handed.

I was distressed. I began talking against the government—why couldn’t they stop the vehicle and give me my property?

We now had literally nothing, so I decided to go to the Ethiopia refugee camp in Itang. But security forces had heard about my complaints against the government, so they arrested me and took me back to their military barrack. Fearing that I would be killed, my neighbors and church members protested and demanded that I be released.

In response, the police asked soldiers to release me into their custody. But community leaders still feared for my safety and asked that I be released to a neighbor’s home for house arrest. The police obliged. But still church members were afraid that I would be taken by soldiers in the night and killed. They wanted me to flee. We realized their fears were right, so Rachel and some relatives left town and traveled forty-five miles away where they stopped and waited for me. Then I followed them. On April 7, 1987, we left that place and traveled for seven days until we reached the Itang refugee camp in Ethiopia.

When we arrived, I sold my Seiko watch and took Rachel to the hospital in Gambella, where she delivered our third child. Three weeks later, we returned to the camp. Although my son, Ezekiel Dhiel, survived childbirth, he died after seven months because we still did not have adequate medical care.

In the camps, aid workers used to steal our food and sell it to Ethiopian merchants, which left us with little to eat. The UN and Ethiopian government promised a small plot of land to any refugee who would till a garden, so I signed up and received one cow as my reward.

I was elected to lead a group of former evangelists in Sudan. Some former members of my youth group came to visit our church. We gathered and worshiped and ate together, then they left to return home.

On their way, an unknown gunman shot one of the girls in the woods. Her name was Rebecca Nyachual Puot, and she died after thirty minutes of bleeding. The next day when I heard about the tragedy, I went to visit the family. But on my way soldiers arrested me, claiming that I knew the killer. The judge ordered me to pay a fine of forty cattle or be executed. I was locked in jail, and the order was written that I must be tortured until I confessed and named any neighbors or relatives who could help pay my fine. I had to work in the commanders’ houses, carrying sixty-five-pound bags of corn on my head. If anyone could not carry the bags, they were beaten.

Sometimes the Sudan People Liberation Movement and Sudan People Liberation Army (SPLM/SPLA) tortured their prisoners by forcing them into a house made of metal in ninety-five-degree weather. When they died, we were forced to remove the bodies and sometimes the stomachs of the corpses collapsed as we carried them out. After seven months, I was finally released when witnesses came to the jail and declared that I was not the killer.

After I was released, I took my exams to qualify for seventh grade. The SPLM/SPLA were forcing young people to join their rebellion, and they seized young children from the villages and sent them to war. This order made it much more difficult to complete our education. We lacked food and water as well as medical care. Rachel became pregnant again, and she needed to go to the Fugnido refugee camp to seek medical treatment. She gave birth to our daughter, Nyawaraga, in the camp.

In 1991 the Ethiopian citizens rebelled against their communist government, and they began to hate us because our rebels were fighting alongside their government, whereas Ethiopian rebels were supported by the Sudan government and the United States. Three friends and I decided to leave Ethiopia and go to a Kenya refugee camp to try to get to Canada, Australia, Europe, or the US. But first we needed money, so we returned to South Sudan to get cows to sell for our journey.

The Socialist Ethiopian Government and their supporters had just been defeated, and refugees were running back to South Sudan, fleeing from the approaching Ethiopian rebels and the Sudan government. At the border refugees were greeted by gunships, and many casualties were being reported. It was terrifying.

We immediately returned to the refugee camp to try to find our families. Two of my friends were able to find their families after twenty-four hours. I heard reports that my family had been seen across the river. After thirty-five hours of traveling without sleep, I finally found them.

After thirty-five hours of traveling without sleep, I finally found them.

Reunited, we returned to my hometown of Ulang where we remained for several months. I returned to Ethiopia and was granted a scholarship by the UN. The extensive trauma my people had endured had its effects. Resentments and quarrels occurred among us. Sometimes we disagreed on what course of action we should take. Then we were dismissed from school by the UN.

Finally we set out for Kenya where other Sudanese refugees had settled. By this time, we had two more children. After another arduous journey, we crossed the border into Kenya, but the government there did not welcome us. I was thrown into jail with my children for days without food or water. Late one evening we convinced Kenyan police to allow us to escape. But our life as refugees in Kenya did not change. We still did not have enough food. Our children had no milk. I was able to find work digging toilets for the equivalent of $4 a week.

The Sudan government wanted to prevent us from going to the US or Canada, so they sent people to Kenya, preaching to the Somalian Muslims there that we were fleeing Sudan because we were rejecting Islam. In response the Somalians began killing Christians. One day they killed two of my neighbors after torturing them. Fighting broke out. The Somalians were shooting people, but we had no guns. We ran to our homes to bring our children to the police station for safety. When I got home, I found that Rachel and some other women had gone to a feeding center to get food. They saw Somalians running toward them. They tried to jump a fence, but Rachel got caught and fell. The Somalians were coming toward her, but they saw a former SPLA soldier shouting, “SPLA Hoyea!” and stopped pursuing her to go after him. As they killed him, an Ethiopian woman called Rachel into her house and hid her until the next day. In the morning, the woman and her husband hid her in wheelbarrow, and took her to the hospital.

We were resettled into two other refugee camps for another nine months. Finally we received resettlement forms to go to the United States. After our interview with the US migration lawyer and our physical exams, Rachel and I were approved to go to the United States with our three children and our nephew. It was April 1994. Our refugee journey had ended, and we began our new life in a new culture with new people.