Of Alderflies and Restoration

Discovering Christ in the crevices of creation

by Chris Bannon | June 5, 2019

As we pursue Christian formation, sometimes lists of fruitful disciplines include prayer, meditating on God’s word, worship, offering thanks, and fasting—intentional practices that draw us into the presence of God. My personal list would also include standing in a river, waving a stick with the aim of catching small fish that I don’t intend to keep. For me, fly fishing for trout is part pastime, part art form, and part spiritual discipline.

Sometimes the messiness of our world demands a strategic act of disconnection. Trout fishing creates Sabbath space for me—a space beyond the voices of fear and hatred, the realities of injustice and violence, and the false gospels of scarcity and self-protection that propogate them. The river creates a space where I am able to fix my eyes on the revealed Christ where he may be found in the quiet crevices of creation. Truly there is much around us that will break our hearts, if we are paying attention. But there is also much around us by which Christ would comfort and restore us, if we only perceive his presence.

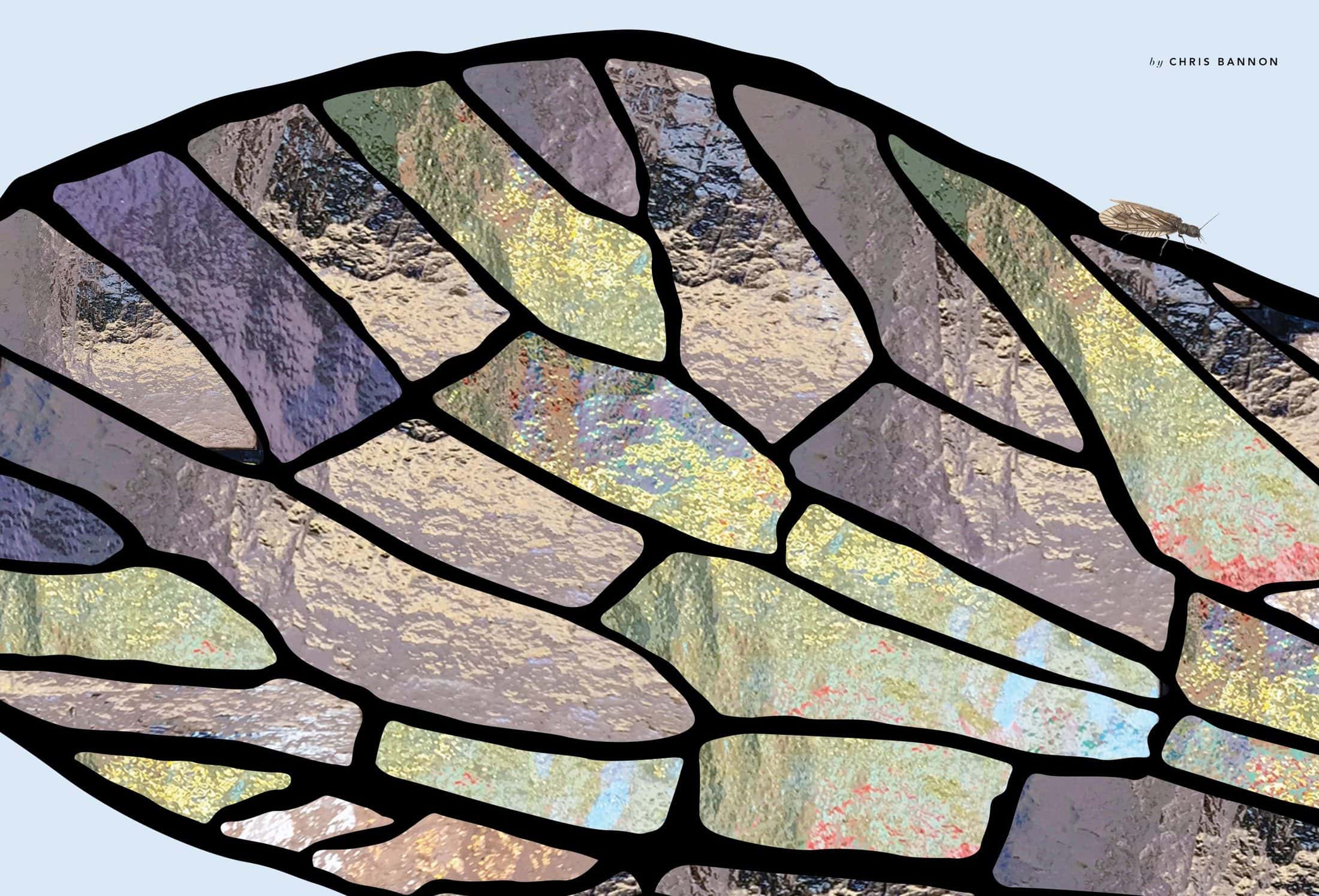

Consider the alderfly.

Laid on the leaves of riverside vegetation, alderfly eggs become larvae that fall into the water below. After a year or more, they grow into adulthood, invisible to the world above. And then, at the appointed time, the aquatic form abandons the river bottom, floating upward. It is carried downstream as wings emerge and flutter. The adult alderfly leaves the water, awkward, fluttering, and fragile. Perfectly timed to cues of sunlight and season, thousands upon thousands of flies discover flight and tumbling clouds of fragile-winged sprites cartwheel through the air.

This will last a day, maybe two. They do not eat or sleep during their time above water. There is only frenetic, awkward flight, egg-laying, and then death. According to nature’s good purpose, they fall lifeless to the surface of the water once again, carried along by the current. It’s a strange, short life. And every stage of it offers a veritable banquet for trout.

How can we believe what

How can we believe what

we claim to believe about God,

yet remain captive to fears

of scarcity and self-protection?

As a full-time pastor, husband, and father of three, I am not nearly as dedicated or accomplished a fly fisherman as I might aspire to be. Nonetheless, my passion for fly fishing is a noteworthy part of me. An introvert by nature and extrovert by vocation, I experience purely aesthetic joy in casting a fly for (generally) small but beautiful fish in remote and beautiful places. The act itself provides healing to my all-too-often harried soul. So I make time to find my way to the river as often as I can.

In mid to late June, at the height of the alderfly hatch on the Androscoggin River, I take my kids camping. Admittedly, it takes a certain amount of effort to convince children that living in a tent in the woods for three days in the midst of an entomological event resembling a biblical plague is in fact desirable.

Last summer we were joined by my brother and his kids, camped on the banks of the river for the alder hatch. Two dads, two tents, five kids, a fly rod, and one of my favorite places.

We pulled into the campground amid a blinding torrent of north country summer rain. Bolting from the vehicles, we raced for the shelter of a riverbank lean-to. Huddled and dripping in the small open-faced log structure, we looked out over the surface of the water as the assault continued, massive raindrops exploding on impact. My brother and I exchanged a glance, silently wondering what we had gotten ourselves into.

But the storm passed in fairly short order, as they generally do in this country. The late afternoon sun broke through the remaining clouds, the children raced out from beneath the shelter to explore, and my brother and I began the process of making camp. As sunlight warmed the air, a smattering of alderflies began to emerge from the river, taking flight in the makings of an afternoon hatch.

The days that followed were filled with a saturating richness—kids biking, wandering, sinking their toes in the riverbank mud, net-fishing for minnows, and generally indulging their imaginations in the quiet of the woods. My brother and I sat and talked, read, and periodically cast a line for trout. In the evenings, once the children were retired to tents and sleeping bags, we sat beside the fire, watching the flame and listening to the river. In the darkness, swirling clouds of alderflies gravitated toward the light of the campfire.

In the nearly complete absence of light pollution, the north country darkness was primordial. This was a night sky to be reckoned with, the scope and depth of the display defying me to look away.

Such a love leaves no room for fear, for belief in scarcity, tribalism, or the violence of self-interest.

As I contemplated the overhead spectacle, the conversation turned to spiritual implications, particularly the wonder of a God big enough to birth the vastness of the universe, yet intimate enough to have imagined with equal care and detail the intricacies of the life of the alderfly.

“His eye is on the sparrow,” the old song goes. In truth, the eyes of God regard even less dignified creatures. I am compelled to wonder: If the God we find revealed in Scripture and in Christ is both immeasurably vast and intimately near, why are we so easily convinced to live in a place of fear? How can we claim Christ while allowing our humanity to be reduced to competition and survival by the economies of nationalism, racism, and the gospel of the free market? How can we believe what we claim to believe about God, yet remain captive to fears of scarcity and self-protection?

In Christ the self-revelation of God declares that we are not nameless matter, scratching out our own survival in a vast and faceless universe. Rather, our lives have been ordained. We are purposed, provided for, and known. In Jesus we claim nothing less than that the entire weight of the immeasurable cosmos bends toward us in love. It is a brash and spectacular claim, but the gospel is this or it is nothing at all. Such a love leaves no room for fear, for belief in scarcity, tribalism, or the violence of self-interest. In the eyes and embrace of such a God, what could we imagine that we might otherwise lack? His eye is on even the alderfly, and we are perfectly loved.

About the Author

Chris Bannon is the founding pastor of the Commons Covenant Church in Rochester, New Hampshire, where he has served since 2014. He is passionate about the preaching and teaching of Scripture, discipleship, culture-making, fly fishing, and good barbecue. When not in the pulpit or otherwise disturbing the peace, he can usually be found spending time with family and friends somewhere out of doors.