Twenty-Two Years After His First Sankofa Journey, Jelani Greenidge Got Back on The Bus

In 2000, I embarked on a Sankofa bus journey from Chicago to visit the sites in a variety of Southern cities that were emblematic of the civil rights movement. The African word “Sankofa” was chosen because of its historical connotations, carrying a broad meaning of “looking back in order to move forward.”

Last month, I got back on the bus. Not only was I long overdue for a visceral refresher of the struggle, but I was curious how the trip would feel after more than two decades. Could it be as transformative as it was the first time?

On my first trip, Sankofa was in its second year, having just been established by Jim Lundeen, Harold Spooner, and Jim Sundholm as part of the compassion, mercy, and justice programming under Covenant Ministries of Benevolence. Seven years later Debbie Blue was installed as executive minister of the new department of Compassion, Mercy, and Justice. Now Sankofa is led by Dominique Gilliard, director of racial righteousness and reconciliation for Love Mercy Do Justice.

Today the basic setup is the same. Participants are paired off, usually a white person with a partner who is BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and other People of Color) heritage. Of course, that term was not in regular usage back then, even though the reasons for its proliferation were as salient then as they are now.

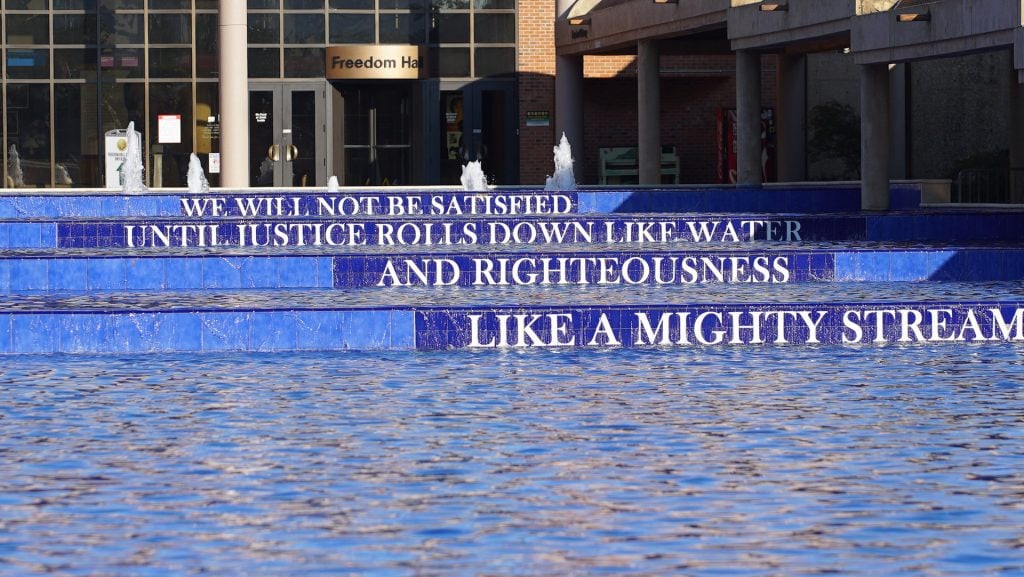

Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historical Park in Atlanta, Georgia.

The biggest difference I noticed is the change in the dialogue around racial justice and equity. Those conversations around the structural systemic problem of racism have more thoroughly entered our cultural mainstream than they had 20 years ago. In a sense, our recent Sankofa journey became a continuation of a broader conversation around racial justice in a context where deeper connection is facilitated through one-on-one and group interactions. Some of us are accustomed to talking about these issues on social media, but when those conversations are mediated through text on a screen, the experience is more abstract and disembodied. On Sankofa, we were with real, flesh-and-blood people, talking about the experiences, lives, and deaths of other flesh-and-blood people.

My personal highlight was the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Alabama, where we experienced both the Legacy Museum and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice. As my fellow Covenanter Sanetta Ponton wrote recently, I felt the tension of both trauma and tenderness as I walked through the hanging monuments in the National Memorial for Peace and Justice that bear witness to our nation’s terrible history of lynching. At the Legacy Museum, a curated collection of images, videos, and artifacts trace the history of American oppression and disenfranchisement of Black people through slavery, Jim Crow, reconstruction and its backlash, and into our current era of mass incarceration.

From the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama.

I was particularly struck by one moment at the beginning of the Legacy Museum. Just after walking past the entryway, I was greeted by a giant screen with an image of a towering wave of water, signifying the ocean as an entry point into the story of the transatlantic slave trade. It reminded me of the deaths of approximately two million Black people who never survived the middle passage, many of whom were tossed overboard at sea. Because I live in a state that borders the Pacific Ocean, I’m used to viewing the ocean primarily as a vast, majestic symbol of God’s goodness. But many Oregon beach towns have signage about what to do if a tsunami causes a giant wave of water to crash onshore. (Spoiler alert: Go to higher ground.) That giant wave of water in the Legacy Museum evoked some of my latent anxiety about emergency preparedness for things like tsunamis or earthquakes, and it hit me—they weren’t ready for this. Those Black folks had no way of preparing themselves for the horrors they would experience on those ships.

And here I was, grappling with that horror. I wasn’t ready, either.

I wondered if I would ever be able to enjoy the ocean again. Because during the hot summertime months, the last thing you want to do is gather your friends and family to go to a mass graveyard of millions of ungrieved souls. What good is a spiritual awakening if you can’t enjoy a day at the beach?

Elaine Lee Turner, giving a guided tour to Sankofa participants in Memphis, Tennessee.

Later, we listened to a woman named Elaine Turner wax eloquent inside the Slave Haven Museum, a converted house used as a refuge for slaves as part of the Underground Railroad. She showed us a painting depicting the souls of those lost during the middle passage—in the ocean. But their faces were not contorted in horror. They were rejoicing, for their suffering had ended. It reminded me that water represents not only death and danger, but also renewal and transformation through baptism.

It’s easier to appreciate the freedom you’ve been given once you understand the price that’s been paid for it.

As it turns out, the word “Sankofa” has a more literal translation in the Akan Twi language of Ghana. It means “to retrieve.” As Americans, we’re all shaped by this history, whether we’re aware of it or not. We cannot move forward with integrity unless we reckon with it. But in order to do that, we must first retrieve it. Our transformation into beloved community requires nothing less.

“Rise Up” by Hank Willis Thomas, from the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama.

As a college student, I was burgeoning with wide-eyed idealism, knowledgable (I thought) about how the world works but hopeful about how it could be different. Now in my mid-forties, I can see better through the illusion of lofty rhetoric without meaningful follow-through. I’ve seen firsthand that change is possible, but it’s costly.

In John 8, Jesus tells his disciples that they will know the truth, and the truth will set them free. Reckoning with the truth and finding our place in it brings a freedom. Relationships can be forged, and progress can be made. It’s hard work but worth it. My experience with my partner on my first Sankofa was equal parts meaningful, intense, and awkward. But we pushed through it, and we’re better off for it.

Granted, my situation was not typical. In order to make the numbers work, I was paired off with my white girlfriend at the time. We were used to having long conversations, but not being stuck on a bus together for hours on end, confronting scene after scene of racial baggage.

But we stuck it out. And I guess we must’ve done something right, because a few weeks ago we celebrated 18 years of marriage together.

And maybe that’s the best thing overall about being on the Sankofa. Talking with a community of believers who are committed to working through our troublesome past gives me a buoyant sense of hope. Like a couple on their anniversary, I can see how far we’ve come, especially considering where we started. We may not be where we should be, but thank the Lord we’re not where we used to be.