Saying "Yes" to Alaska

My plane lifts smoothly from the gravel runway into a mild blue sky with the sparkling waters of the Norton Sound outside my window. A crab boat is drifting off the shore of the village of Elim, Alaska. It seems only yesterday that I was landing here, but two weeks have flown by. I will soon be spending the night in Nome and after three more flights will land at Kansas City International Airport. I want to go home, but I’m sad to leave.

Twelve years ago, my son graduated from North Park University and joined the staff at KICY Radio in Nome, which serves as the primary source of Christian teaching for many remote believers. Most village churches the Covenant serves across western Alaska do not have a full-time pastor. Serving a village church is a unique calling. Residents participate in subsistence living. Attracting ministers from outside the region means addressing the cost of travel; the high cost of living; long cold, dark winters; and a culture that is unfamiliar to residents in the Lower 48.

Last year as I planned for a sabbatical during the summer months, the thought came to me that I could visit one of those communities. Marc Murchison, a former village pastor, had an idea for short-term pastoral service to remote churches. Conversations with Marc and Curtis Ivanoff, Alaska Conference superintendent, led to a plan.

Well, it wasn’t exactly a plan. It was more like a reconnaissance mission combined with improvisational theater. I packed a sleeping bag, some sturdy outdoor clothing, and a stack of teaching materials. I really didn’t know what I needed. I discovered that my best tools were an open heart and a handy “yes.”

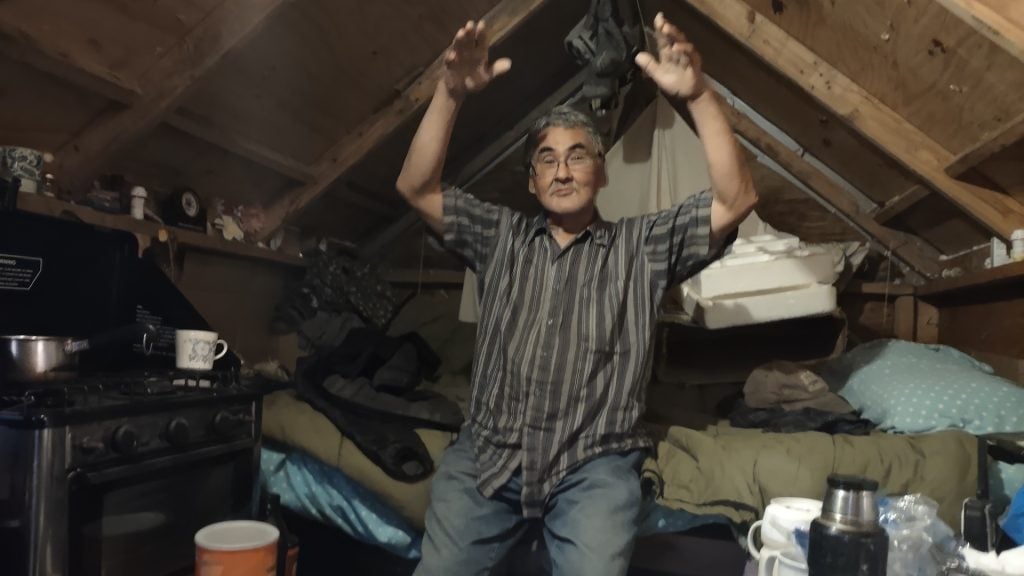

Kenny Takak – Chair of Elim Covenant Church

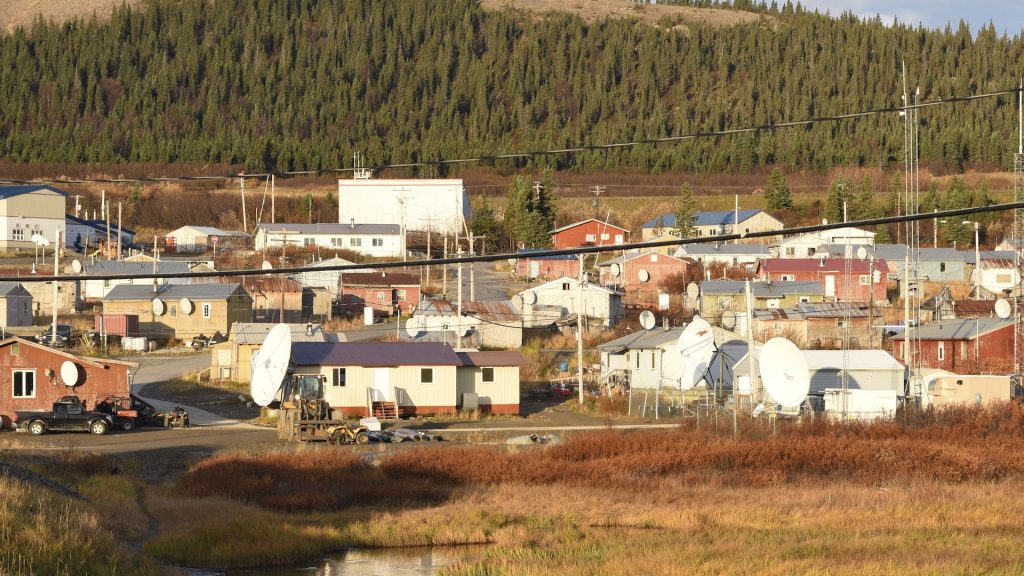

On my arrival, I was warmly greeted by Kenny Takak, chair of Elim Covenant Church, and his wife, Grace. When they asked if I wanted a tour of the town, I said yes, and we threw my gear in the back of their pickup truck. I took in the bright pink fireweed against the dark spruce forest surrounding the village of Elim. The gorgeous scenery gave way to a jumble of small, weathered buildings with no uniformity. Outside the structures were rusty vehicles, piles of odd mechanical parts, and the occasional set of moose antlers. When I realized the structures were homes, I assumed the little neighborhood to be in deep poverty. That was my first mistake.

Later when I was invited into some of those homes, I learned that the interiors did not match the exteriors. I learned that goodwill among neighbors was earned not by following a property zoning code but by sharing what you have. What I thought was a junk pile was a salvage store. The words “reuse, recycle, repurpose” are not just virtues in Elim. They are survival skills.

I had been warned that the pace of life would be slower than I’m used to. I was advised to be patient and slow down. But I learned that I didn’t have to slow down as much as I had to pace myself. Every night I was tired from the constant activity of the day. I learned that village life takes much more effort than my typical rhythms. That effort is matched to the rhythm of nature.

Shelby David – Trail Guide

As I sat in that plane watching the rugged Alaskan coast below, I remembered a long hike with an elderly man named Shelby. When he invited me to walk with him, I said yes. We spent most of the morning talking about life in the village. His grandmother was a well-known healer.

“Was she a shaman?” I asked.

“No, she was more like a folk doctor and a psychologist. She was easy to talk to, and she knew about herbal remedies.” Shelby lived in a home without electricity, and his wife had died two years ago. But he wasn’t troubled by his solitude.

After leaving Shelby to his secret fishing hole, I retraced our steps back to the village. I came upon a trail near town that looked inviting, so I said yes. As I explored the trail, I noticed a small cross on the edge of the brush. Approaching the cross, I found many more crosses. The summer growth had nearly consumed the village cemetery. The grave markers had dates going back many decades. Still more markers were so worn that the dates and names were no longer legible. I toured the cemetery and emerged atop a cliff with a breathtaking view of the sea.

I later met a man named Louis who had grown up in another village. For a time, he was a tribal mortician. He followed traditional customs and took his work seriously. Preparing a body for a memorial was an important Christian ministry. Louis wanted to create a public map of the cemetery to record the grave sites. He had not yet attended Elim Covenant Church, and he asked me if I, as a pastor, could poke around the church for records of gravesites. I said yes.

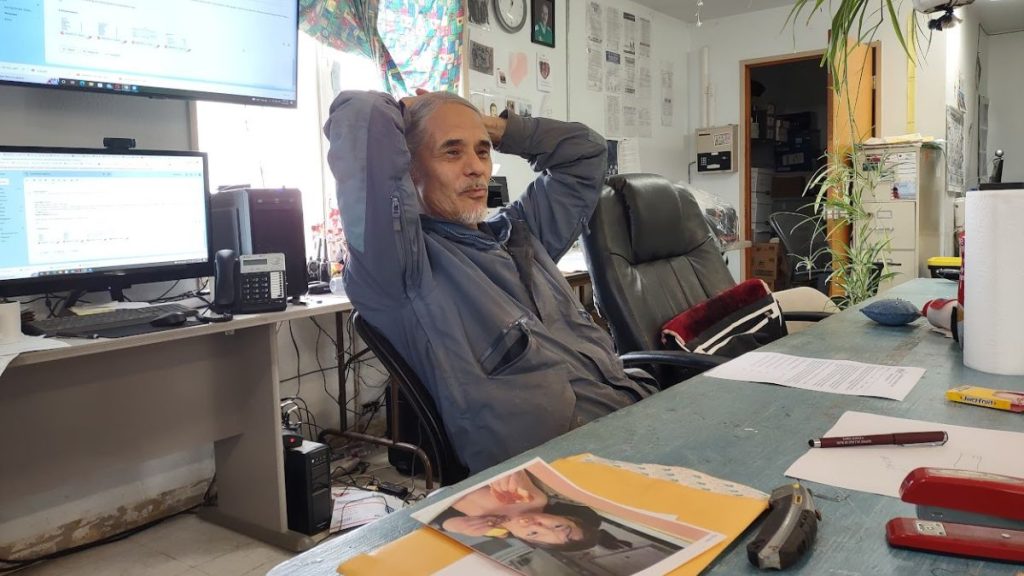

Michael Murray – Village Historian

That led me to a man named Michael who had lived in Elim nearly 70 years. He was filled with stories going back to the arrival of Christianity to the region. Michael had a career in handling hazardous materials, was a volunteer firefighter, and an organizer for the Iditarod sled dog race. He was also sure he could name all the sites in the cemetery. I asked about creating a record. He pointed to his head and said, “This is a record.” I asked what happens to the record when he is gone? He shrugged and said, “We keep our history by telling our stories.”

One day I was invited into the tribal corporate offices, and I said yes. The desks were nearly buried in papers, boxes, and architectural drawings. The corporate president, Robert Keith, explained the network of Native organizations that provide for various village services. He took me to a map on the wall and pointed to several locations along the shore of the Norton Sound, telling me about historical events as far back as the flu epidemic of 1917.

Robert Keith – Tribal Corporate President

One day I was invited into the school, and I said yes. They were conducting an open house, and I was treated as a parent or a guardian. The facility is beautiful and modern. Display cases were filled with Native history exhibits. I met all the teachers from kindergarten through high school. Each staff member had a story about how they got there.

Another day, Kenny and Grace invited me to “fish camp.” I said, “Yes, please!” I love fishing, but I had to remind myself that this would not be the usual sport fishing I am used to. The sprawling river delta that empties into the sea is called Moses Point. Tiny cabins are scattered about, each surrounded by boats, trucks, and ATVs. Here, twelve miles from town, villagers gather their winter food. Kenny navigated the river system to a favorite hotspot, and we reeled in more than 40 pounds of silver salmon. It was riotous fun, but then we had to clean them and preserve them—a task that took us late into the night. Using the traditional ulu knife, Grace taught me how every part of the fish would be used. Even the small remains were thoughtfully cut into pieces for the birds to carry away. Grace told me, “The gulls have to eat too.”

Grace Takak – Village Host

Residents of Elim were generous not only with their belongings but with their time and their stories. The hospitality I experienced there was a great gift. I couldn’t help but wonder, “Where is the indifference to outsiders? Where are the social problems—the alcohol abuse, teen suicide, and domestic violence—I’ve heard about?” Those problems persist and I did have the chance to pray with some hurting people. But I learned that the community is not defined by social challenges. I witnessed both joy and sorrow in the people there.

I began my farewell sermon with a list of people who had shown me great kindness during my visit. It was a long list. The communion service that followed brought me to tears. I’m wiping my eyes again as my plane descends toward Nome. I’m looking forward to conveniences like a hot shower, a cold drink, and a juicy hamburger. I smile to remember that I used to consider Nome as an outpost of civilization. Now it feels like a big city.

Elim, Alaska, changed me. My heart got a little bigger, and my problems back home became smaller. I’m sure I will be back somehow.

Photo of Elim, Alaska by Curits Ivanoff

POSTSCRIPT: Two weeks after I returned home, a massive storm and hurricane force winds struck the villages of the Norton Sound. No loss of life was reported, but the destruction was extensive. When I returned to Alaska for a KICY board meeting, I witnessed some of the damage in Nome. Kenny Takak reported that nearly every cabin at Moses Point was washed away. At least 19 homes in Golovan were temporarily uninhabitable, displacing entire families. In Hooper Bay, as many as 20 people were housed in the Covenant church for several days. With winter weather coming, repairs were urgent. Multiple government and Christian relief agencies cooperated with the Alaska Conference and Covenant World Relief and Development. Superintendent Curtis Ivanoff described the current effort as triage. “We have a long game in view,” he says. “These are our people and our family.”