[vc_row el_class=”header”][vc_column width=”1/1″][vc_single_image image=”22909″ border_color=”grey” img_link_target=”_self” img_size=”full” alignment=”center”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row el_class=”header” css=”.vc_custom_1430254245455{margin-top: 50px !important;padding-left: 100px !important;}”][vc_column width=”1/1″][vc_column_text]

Back Where We Started

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

How our idea of vocation keeps us from experiencing a full life

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

By Nancy Nordenson

June 2015

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

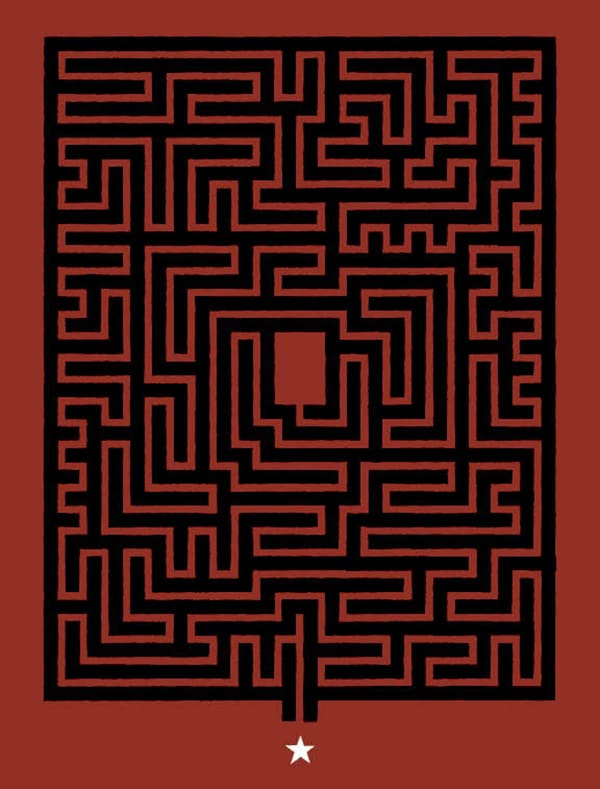

Once, I came across a labyrinth on a hill far from home. It was my first “life-sized” one.

A couple years earlier I had tried dragging my finger along the arcs of a finger labyrinth I found in a basket next to me in a chapel as I sat alone trying to pray. But the finger dragging produced no great spiritual effect. I suspected I had done it wrong, looking for that end result that would qualify the experience as worthwhile. The receptive meditative state I had failed to achieve and the dashed hope that my fingers would channel some sort of message reminded me of when I was one of several sixth-grade girls at a slumber party playing with a disallowed Ouija board. “What’s the name of the boy I’m going to marry?” we took turns asking with nervous giggles. Nonsense responses of jumbled letters emerged for each of us in turn as our fingers nervously rode the planchette around the board. We knew even then that futures were hidden.

When I found the labyrinth on the hill, I placed each foot in turn—right, left, right—on the red paver stones that formed its path. No expectations: I’d walk it, that’s all. Hurry through. An afternoon rain was stepping over the horizon, and in my backpack a Snickers bar with almonds softened in the high heat. Green pavers traced the perimeter of the circular whole and filled the interstices between the path’s switchback turns.

I tried not to look ahead or anticipate the directional flips, back and forth, around and around, that prevented me from being able to predict with certainty where I was headed and when I would arrive. I looked only where my foot was about to land. A few months earlier, I’d read Jean-Pierre de Caussade’s The Sacrament of the Present Moment. Its call to attend to the here and now pressed upon me, “Our souls can only be truly nourished, strengthened, enriched, and sanctified by the bounty of the present moment. What more can we ask?”

No startling insights bubbled up as I walked. Shall I blame the loud women and children talking and playing at the labyrinth’s entrance? Was it me, hurrying to avoid the rain, hungry for the chocolate I carried? Or was it just the way it is? Long paths, and still no clue as to the direction change, no seeming progress toward a hidden destination, but you keep walking because a place is provided in which to step, and so you go.

The day ahead often reads like an unopened book. Its outline is apparent, but you can’t know its twists and turns. Sometimes I’m afraid of it. On my wedding day, my grandfather—he in his dark suit, I in my long white dress—recited words from an old poem to me, ever so quietly and gently, “Go out into the darkness and put your hand into the hand of God. That shall be to you better than light and safer than a known way.”

You can walk this path forever—inward and outward and inward again—always hoping for how the story will end. Often I think I’ve figured out a story’s conclusion in advance but then find that I’ve been wrong, as if by grabbing hold of one end of the narrative thread I could see where the other end finally anchors and trace the in-between.

[/vc_column_text][vc_separator color=”grey”][vc_column_text]

When you get to the center of a labyrinth, you can’t see the cross that was drawn to seed the structure. There is only a space. The center may be no bigger than the circumference of an average adult, but it is a place of hospitality. You can stay as long as you want.

Some time after the labyrinth on the hill, I came upon one mowed into a small field. At the intersection of the arms of the Greek cross was a hard desk chair. I sat in it and thought awhile. The path had led to a spacious place. I closed my eyes and turned my face to the afternoon sun.

[/vc_column_text][vc_separator color=”grey”][vc_column_text]

Dreams of freedom had been filling my head. Here was my plan: cut back on paid client work and let my husband’s earnings cover most of the bills while I wrote my own words, at least for a while. There were all kinds of good reasons for this plan, not the least of which was an inner sensation that bore the voiceprint of call issued from a realm beyond. I wanted to respond, to answer. I wanted to call back.

My husband agreed to the plan with smiles and cheers. Someday it would happen. We waited.

Then, after turbulent years of my husband’s un- and underemployment and job searching, that “someday” appeared to arrive. Secure in a new job and with more than a year under his belt plus an early promotion, he was earning enough for me to let go of the majority household income demands. “Start turning down some work projects,” he said.

We were still flush with peace over the start of this new phase in life, only days into it, when he came home with the hushed choked news of job loss.

Within a week, I said yes to three new paying projects. Responsibility, Bonhoeffer reminds me. My husband—devastated, devastated—typed up a new résumé and began again the search for a job. The years drag on.

The road forward turns back on itself with no apparent progress made, and here we are again where we started. A labyrinth’s exit and entrance are one and the same, depending on what you do with it. You can call it quits or pivot and start again toward the center.

[/vc_column_text][vc_separator color=”grey”][vc_column_text]

Far from the labyrinth on the hill, I’m walking today with my sunglasses on, though the day is cloudy. Compounding work crises carry the weight of the proverbial last straw that, if not actually breaking the camel’s back, force compression cracks and pain. Don’t cry at work, the experts tell you; I work at home yet try to heed the advice. I’m walking it off, blinking it back, letting things settle and pack down so there is room inside for more.

I’ve wanted to quit my work for hire, but the path under my feet hasn’t allowed it. How can I make peace with that?

Two devotional readings compete for my attention. From Ecclesiastes, a question and a complaint, “What do people get for all the toil and anxious striving with which they labor under the sun? All their days their work is grief and pain; even at night their minds do not rest.” And from a pilgrimage psalm, a blessing, “Blessed are those whose strength is in you, whose hearts are set on pilgrimage.” Walking, I bounce from one text to the other, murmuring grievances with the first reading, quieting myself with the hope in the second.

How can peace be made? The only way that comes to me now is to expand the range of my perceived call, to imagine anew how it can play out.

Take off the sunglasses, dry both eyes, and sit down again at the desk. Hold the complaint in the left hand and hope in the right. In this desk chair is the place where I live. In this office is the field where I attend to life. In this field, whether chosen or given, a treasure has been hidden and the game to find it is on.

Blur the distinction between life and work. It’s all of one piece—unless you don’t allow it to be. Cast your gaze over anything—let your view widen—over even this field of work and what you see growing is life, with meaning everywhere to be cultivated. Hope, wrote Peter Berger, signals a reality beyond reality.

[/vc_column_text][vc_separator color=”grey”][vc_column_text]

Outside the perimeter of the labyrinth on the hill, two men wearing suits stood talking.

“Because there’s no hedge you don’t even have to walk it,” said one man to the other. “You can just follow it through with your eyes and see where it goes.”

Neither the Camino de Santiago nor the Appalachian Trail, this pilgrimage is mine. It began with my last failed plan, yet dates back to my first passage through the door of a job. It takes me from project to project—not from relic to relic, or season to season, or outpost to outpost. If I manage not to step away, I just might figure out ways to understand life through the labor.

There may be more of us who need to make peace with staying on a path than there are those who should step away to something new. Even Thoreau had to leave Walden and return to selling pencils. Staying in place can be pilgrimage too.

This walking and turning and walking again takes time. It’s tempting to jump ahead with a glance—or a wish—and skip the here-and-now steps along the physical stone path. It’s tempting to step away, to join the suited men who hold back their bodies from the next step, substituting instead a quick assessment from a safe distance. It’s tempting to ride our mental planchettes around the various possibilities of how things will play themselves out.

In reality, though, only two options exist: walk through or step away.

I recently read that you first must find out who you are in order to find work you love. That notion, ideal and lovely when talking to a college senior in a career counseling office, too easily glosses over another reality: wrestling with work, loving it or not; rising back up after the match but, like Jacob, walking away with a limp; only then discovering an identity for yourself you never knew and the identity of the actual partner against whom you wrestled.

My husband has found a job at the small gym down our street. Far from who he thought he was, he now manages machines that can make you strong and the gym’s members who use them. It’s not quite full-time, and there is no health insurance or 401K, but it is something. More than something. It seems we can’t go anywhere without running into someone who knows him from the gym and gives him a wave or stops to talk. We smile at his popularity. Behind the smile is the ongoing job search for the work he’d rather be doing that’s still beyond his reach.

I may not have ever walked a labyrinth before, but I knew this much: your feet must touch the path, your fingers slicing the air as they move, your body one step further and another. Your eyes may not be able to see beyond where you are now, and that must sometimes be enough. I’m practicing not glossing over the little words that pop up in the Psalms now and again in the orthodox version I sometimes read, “So be it.” Breath in; breath out; left right left.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/1″][vc_separator color=”grey”][vc_column_text]About the Author

Nancy Nordenson is a freelance medical writer whose writing has appeared in Harvard Divinity Bulletin, Comment, and other publications. She is a member of Bethlehem Covenant Church in Minneapolis. Although she’s lived in Minnesota most of her adult life, her longing for a coastal beach, arising from her years growing up in Florida, remains strong. Find out more at nancynordenson.com.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]