[vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text] [/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

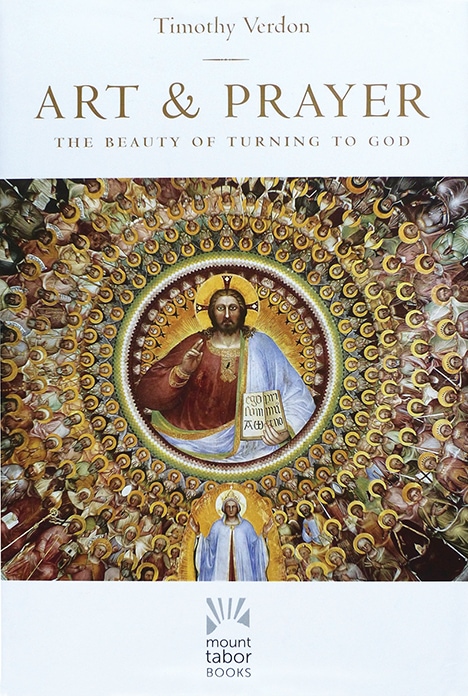

Art and Prayer: The Beauty of Turning to God

Timothy Verdon

Paraclete, 320 pages

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/1″][vc_column_text]

Reviewed By Linda Chestney | January 13, 2016

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Prayer has been a struggle for me throughout my life. I committed my life to Christ as a teen in a small Baptist church in South Dakota. I dutifully prayed, but had questions about why I was doing it. If God knows everything, what’s the point of prayer? I wondered why I should pray because a mighty God who created the universe certainly didn’t need to hear from me about petty issues. As I grew in faith and in maturity, I fortuitously happened across Philip Yancey’s book Prayer: Does It Make Any Difference? There I landed on the life-changing assertion he made in the book, “Pray because Jesus prayed.” And that’s made all the difference.

I recently consumed Monsignor Timothy Verdon’s Art and Prayer: The Beauty of Turning to God. It is a life-enriching book. Verdon, who earned his PhD at Yale University and has lived for the last fifty years in Florence, Italy, where he directs the Diocesan Office of Sacred Art and Church Cultural Heritage, is an art historian and scholar. As a visual and written word person, I write art reviews for magazines and online publications—and have studied art history. So Verdon’s book spoke to my heart.

I was brought up in the Protestant faith (Baptist, Congregational, Covenant), so some of the terms in Verdon’s book were a stretch as my exposure to Catholicism is limited, but the concepts on prayer and art are transferable.

Focusing mostly on Renaissance art—with works by van Eyck, Holbein, da Vinci, Titian, Michelangelo in a lavishly illustrated book with more than 100 images—Verdon emphasizes that art of that time was created when most viewers were illiterate. They couldn’t read the Bible or commentaries, they couldn’t Google concepts, they could only listen to stories—or view paintings, architecture, and sculptures.

Verdon explains how sacred images have taught believers how to behave, showing poses and facial expressions in which even nonbelievers immediately recognize a spiritual presence. He says, “These images teach viewers how to pray, and for those who see them, living, believing, and praying seem to be the same thing.”

The paintings of the time are often laden with iconic symbols. Some are obvious (the white dove representing the Holy Spirit, the haloes depicting holiness), but others are less so (the little dog signifying friendship). Each communicates theological concepts that are profound. For example, a fourteenth-century painting of Mary praying before the infant Jesus subtly suggests that we can all pray to Jesus.

“Prayer is an interior dialogue in which we express the disappointments that make us doubt God’s love,” Verdon explains, “and he powerfully reaffirms the sense of his promises, opening our eyes to the signs of his faithfulness with which the universe abounds.”

Absorbing the artworks in this book with Verdon’s skillful ability to paint a picture of the culture, the themes, the symbolism is enlightening. The two arenas of art and prayer, juxtaposed, enrich each other. This is an excellent read.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]