By Stan Friedman

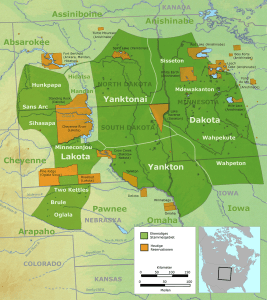

CHICAGO, IL (December 9, 2016) – Zoey Tizon, a North Park University student who was hosed down by police using water cannons in subfreezing temperatures at the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in North Dakota last month, said she is excited that the Army Corp of Engineers refused to grant a final construction permit for the Dakota Access Pipeline project (DAPL) last Sunday, but she remains cautious about the future.

“It is a time for celebrating,” said Tizon, who had helped organize more than 20 North Park students to travel to the reservation. But she noted that the Corp’s refusal to grant a key easement was only temporary so more studies could be conducted on possible environmental impacts. Native Americans have opposed the project because it passes near tribal lands and under the Missouri River, and they fear potential harm to their water supply.

Caleb McIlraith, who attends Gathering House Covenant Church (Spokane, Wash.), said he felt “relief followed by apprehension” when he heard the news about the Corp’s decision. “I don’t feel super trusting,” he added.

Caleb McIlraith, who attends Gathering House Covenant Church (Spokane, Wash.), said he felt “relief followed by apprehension” when he heard the news about the Corp’s decision. “I don’t feel super trusting,” he added.

I think this news of easement denial is gift and grace, especially in the midst of what may turn out to be a long a bitter winter,” said Mark Tao, pastor of Immanuel Covenant Church in Chicago, who joined at least 500 clergy from around the country who traveled to Standing Rock in early November. “Maybe it will even allow some to leave the frigid conditions of camp for a while. But there isn’t a doubt in my mind that there will be a need to remain further.”

Tao pointed to the statement released last Sunday by the pipeline’s operator Energy Transfer Partners, which declared the company is “fully committed to ensuring that this vital project is brought to completion and fully expect to complete construction of the pipeline without any additional rerouting in and around Lake Oahe. Nothing this Administration has done today changes that in any way.”

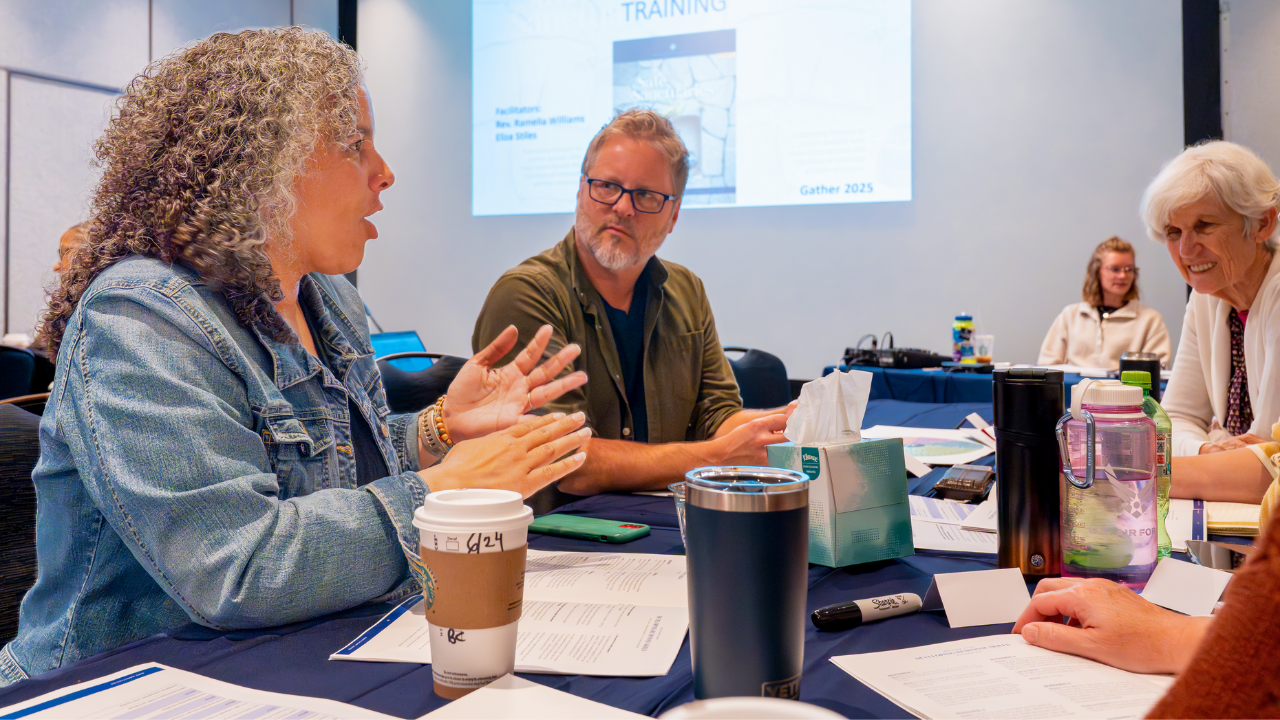

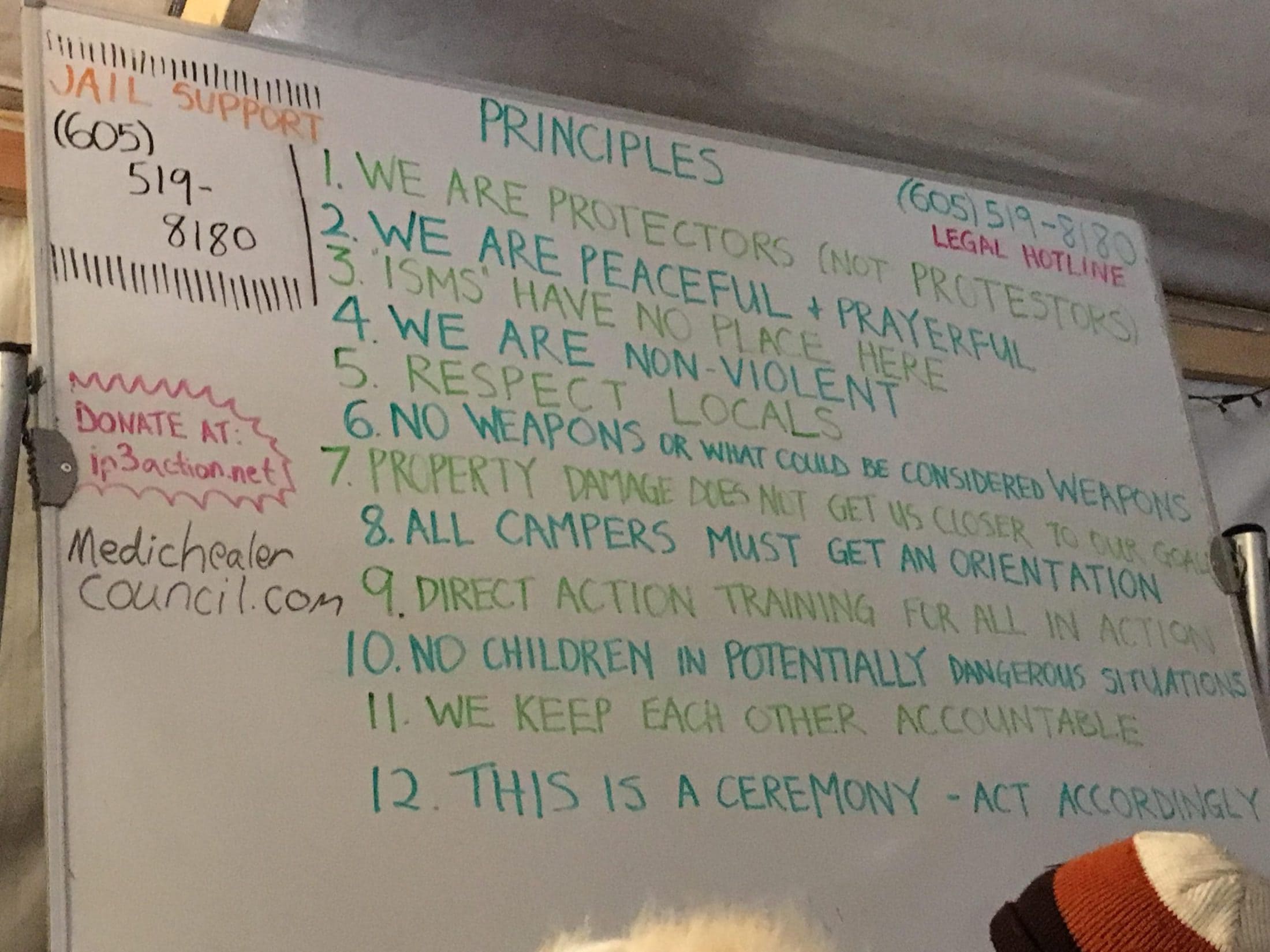

The Covenanters were among thousands of people who have joined the tribes, who view themselves as “water protectors” rather than protestors. They refer to the people who joined them as “friends.”

During their times at the camp—most stayed for less than a week—the Covenanters helped with supportive duties such as splitting firewood and sorting donations of food and clothing. For the most part, only Native Americans were involved in the civil disobedience at the front lines, which actually took up a small piece of land around a bridge.

Tizon was doused with water while bringing blankets and dry clothes to others who had been soaked on the front lines the night of November 20. Police in riot gear also fired tear gas, rubber bullets, and concussion grenades to keep activists from crossing a bridge to the construction site. Police said protesters had acted threateningly, but others at the scene deny the claim.

Tizon said that it was difficult to remove clothes from people who had been brought back to medical tents because the drenched garments had frozen stiff.

All of the Covenanters said they were inspired by the tribes’ determination that the entire effort be covered in prayer. The campaign by the Native Americans started April 1 with a nearly 30-mile prayer ride on horseback.

A writer for Religion News Service noted, “That prayer has continued in the camps since then: communal prayers in the morning and evening and at mealtimes; prayers in vigils and in songs; prayers while sage, cedar and tobacco are burned.” She added, “And the Standing Rock Sioux have invited all people to join.”

“Just the emphasis on prayer all day and all night in song and dance was so powerful,” said Taylor McIlraith, Caleb’s wife. “They prayed for everyone, including the people who disagreed with them.”

Most of the people who arrived to help have done so for reasons that include environmentalism and to protest historic injustices against Native Americans. The tribes share those concerns but their actions are most rooted in the integral connection between their faith and land, Tao said.

Covenanters also said they admired that the Native Americans had committed to nonviolence and people were expected to take part in special training. “If you weren’t committed to nonviolence, they wanted you to leave,” Tizon said.

Tao said he is committed to doing what he can to bring attention to the situation at the reservation but also to injustices committed against Native Americans.

“We have to keep pressing in, keep expressing solidarity, keep doing that hard work of laboring for what is ethical, right, and just and protesting what is wrong, unethical, and unjust in our world,” he said. “We need to discuss how we might or might not be complicit in these kinds of patterns and social tapestry of our nation.”