[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Epiphany

Artists see the world differently because of Temma Lowly

By Stan Friedman | January 5, 2018

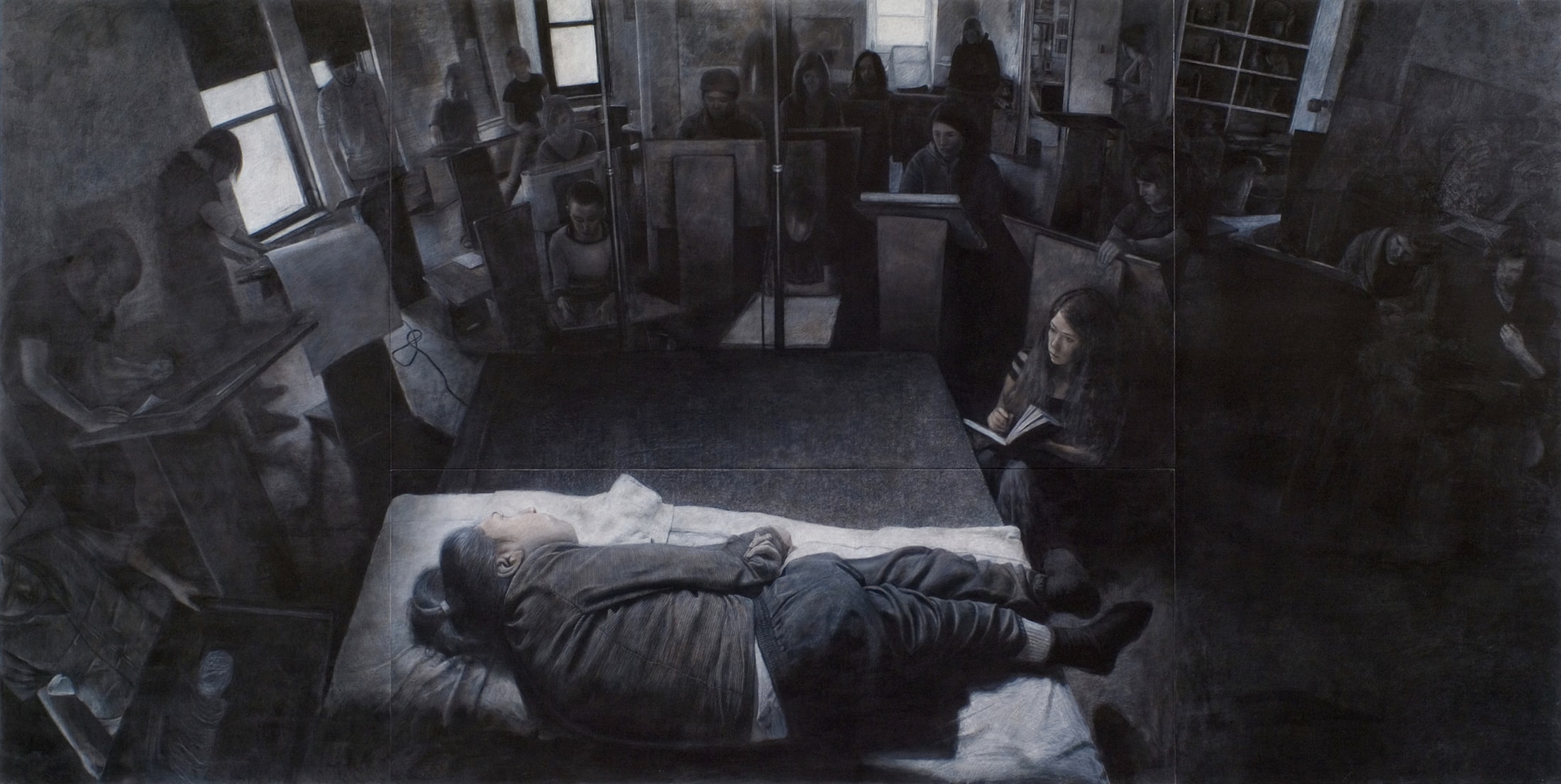

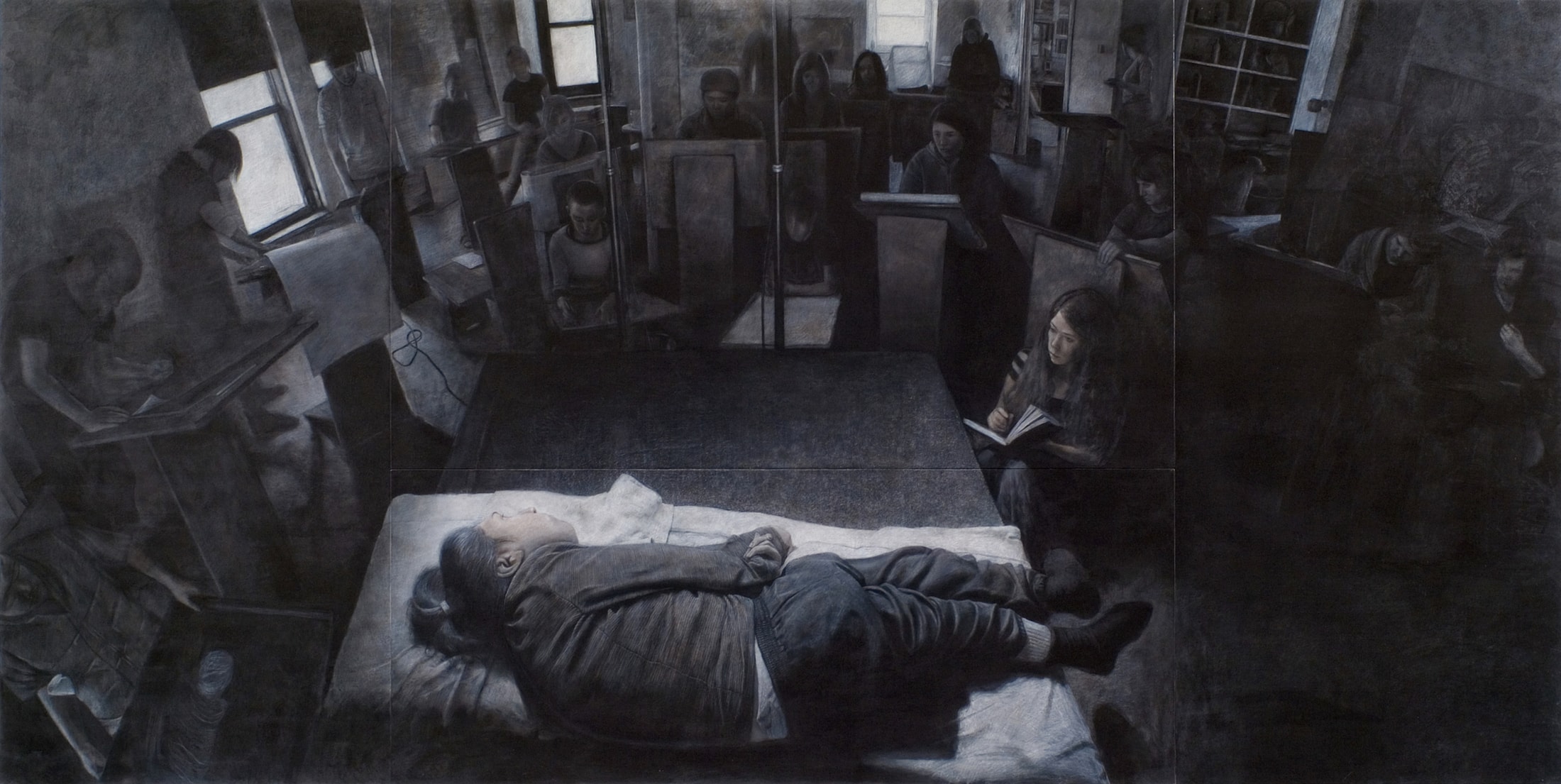

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Tim Lowly’s large-scale triptych “Culture of Adoration,” disorients first-time observers, who find themselves gazing down upon his students drawing the artist’s profoundly disabled daughter, Temma. Centered in the foreground, she is one focal point, but so also is the broad ring of students in various shades of light and detail, filling the rest of the canvas. The observers aren’t sure to whom they should look. Or what to make of their own reaction.

What they also don’t know is how the moment changed the students and others after them.

The drawing (2008, 60″ x 120″) echoes Early Renaissance depictions of the Adoration of the Magi at Jesus’ birth. In their shared act of attentiveness, the students are allusions to community – a kind of culture – coming around and valuing someone who might otherwise be shunned.

Temma, who is bathed in light in the drawing, suffered severe hypoxia after she experienced a temporary loss of oxygen to her brain two days after she was born in 1985. As a result of oxygen being restricted to her brain, she is unable to move voluntarily or communicate, and has occasional seizures. It is impossible to know how or what she thinks. Temma also is cortically blind, which means she can see, but the brain of the young woman who is luminous in “Adoration” apparently can’t make sense of the light that enters her own eyes.

Since 1994, Lowly has been affiliated with North Park University in Chicago as gallery director, professor, and artist-in-residence. Temma has been at the core of his acclaimed work for more than 25 years and the subject of hundreds of pieces. He also has involved her as a subject in several classes.

Lowly’s art leads observers to consider what it means to be the imago dei: made in the image of God. One writer said of Temma presence in “Culture of Adoration, “She is the antithesis of what our culture idealizes, idolizes, adores. … Cipher-like, she seems invulnerable to the laws of logic or aesthetics. Perhaps only some mysterious code of love and devoted, disciplined attention can interpret her secrets.”

(A lengthy, moving piece on the Lowly family, “Temma Lowly and the Meaning of Life” was published in the Chicago Reader in 2002).

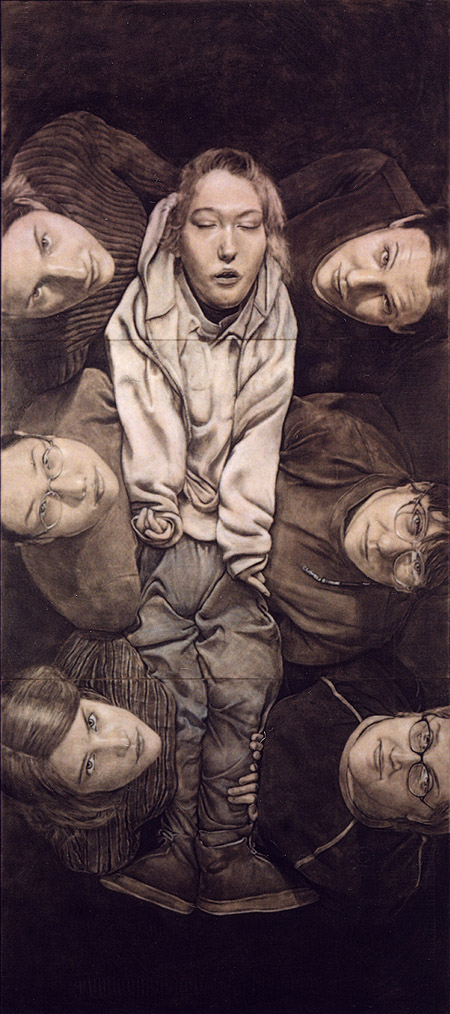

Lowly has involved Temma as a subject in the classroom at various times, but students also have helped him with other projects. In “Carry Me” (2002, drawing on panel, 108″ x 48″) several of the students in an advanced drawing class hold her up and they also helped start the piece. In 2014 several students also participated in a painting titled “The Oxford Temma” made of 24 sections which was presented as a gift to St. Luke’s Church in Oxford, England.

“Fundamentally I want students to have an opportunity to encounter people we’re often told to avoid,” Lowly says. “My desire is to make present and visible people who have been culturally marginalized, people who many view as profoundly ‘other’ than their own experience of what it means to be human.”

Not all of his students initially appreciated the opportunity. One questioned whether it was ethical for the instructor to involve Temma because she was unable to give consent. “I was quite impressed that a student would articulate this,” Lowly says. “I also regretted that I hadn’t explained why we are doing this, so I explained that as Temma’s parent, I wanted to make her present so that she and others like her are not unknown.” The student went on to draw Temma and wrote an article reflecting on the experience.

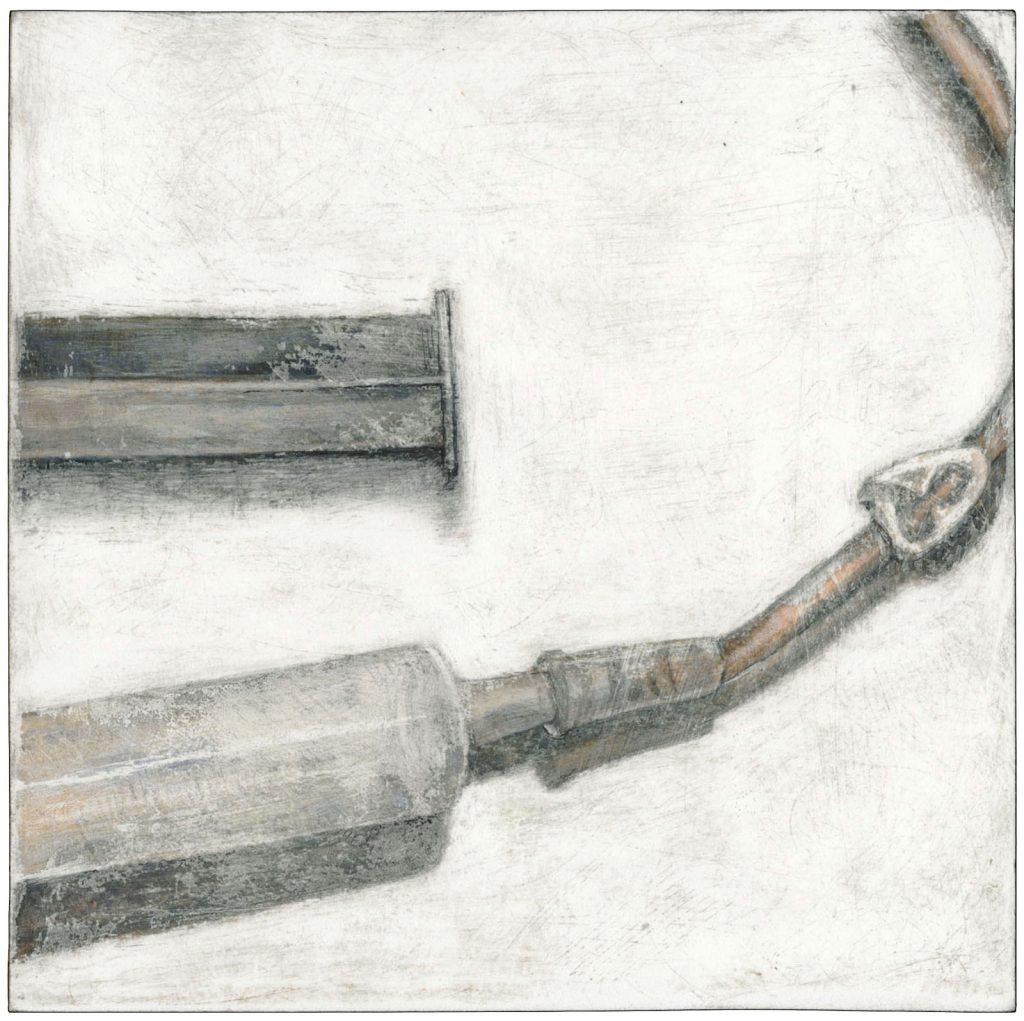

Several of Lowly’s students have been caretakers for Temma, including Rachel M. Gonzalez, one of the students in “Culture of Adoration.” She made a collaborative project with Tim called Temma’s Objects. The project focused on the everyday items that belonged to Temma and used in her care. The works were part of a show in Los Angeles.

Students also have been among the more than 100 people around the country who have contributed to a piece called “Without Moving (After Guy Chase)”. In that painting Temma is wrapped in a towel and blanket and appears to be floating in a void, which Lowly says is suggestive of how many people feel when they meet someone who is profoundly disabled. But what appears to be a void actually is a grey area gradually being covered by more than 400,000 dots applied by participants who have viewed the painting at exhibitions.

Participants count the dots as they paint them. The dots are painted close to each other without touching. The concentration required for this kind of action sometimes leads the participants into a meditative, even prayerful, space.

(Tim was introduced to this idea of art making rooted in contemplative labor by the work of artist Guy Chase. Chase had made a group of drawings on scraps of cardboard where he carefully applied the dots and counted them as he was doing so. He found the act to be one of contemplation and attentiveness that he identified as prayer.)

“One’s first experience of Temma is that we think our reaction should be one of pity,” Lowly says. “But over time you come to see she is profoundly ‘other.’ There is something important and valuable about her, but it is not something you can get with just a superficial meeting with her.”

An experience of drawing Temma is not the same as the Magi’s adoration of Jesus, yet the lives of some of Tim’s students have been changed in their encounter with her, in a similar way as we know the lives of the Magi were changed. Below, several of these students share how their drawing of Temma transformed the way they see the world, people who are “other” and their approach to art.

Rachel M. Gonzalez

I’ve drawn Temma on more occasions than I can count. I first met and drew Temma in my sophomore year, and it was my first drawing class with Tim. I helped him bring her up the stairs in her chair. It was a very memorable day for me. Later, after college, and years after I was Tim’s painting assistant, I became one of Temma’s caregivers. I have a daily personal journal practice and she frequently appeared in my journals.

I didn’t have much experience with people who had disabilities. I had been a caregiver, but those were people with cancer or other maladies. I can say for sure that I wouldn’t be in the career I currently am without her. I can say for sure I wouldn’t have as much empathy or awareness of the less-abled as I am now.

I didn’t have much experience with people who had disabilities. I had been a caregiver, but those were people with cancer or other maladies. I can say for sure that I wouldn’t be in the career I currently am without her. I can say for sure I wouldn’t have as much empathy or awareness of the less-abled as I am now.

And I can say without a doubt that the (art)work I do now is much more collaborative than it was prior to Temma because I am more interested in having a conversation between me and my subject matter than I was when I was just blindly painting things simply because they looked interesting.

I think I’ve wanted to communicate with her instead of about her. Temma has a silent language. Her language is in the body, in objects and all around her. When it’s time to brush teeth, we tap a cup so she feels the vibration and knows what is to come. When we want to capture her interest, we ring a bell. We pull her socks on and off and massage the base of her skull so she feels cared for.

So I think the work I made about Temma, both with and without Tim, was a bit of a meditation on who she was to me. A little bit like making paintings about a celebrity you see a lot of but don’t personally know, Temma has a rich internal world that’s completely unknown to every person around her. That’s fascinating. She’s fascinating. But I can’t say that the work I have made about her is a portrait, it’s only one side of a story.

The piece I’ve included was part of Temma’s Objects series Tim and I collaborated on. It is really important to me because it was the first drawing of Temma that I ever made that didn’t depict her countenance. Rather it depicted a part of her daily life that I found profoundly grotesque at first. It was the tool I used to feed her every day through a tube in her stomach.

I have to say it was the closest I ever got to a person, these daily feedings. And after a time I started to look forward to mealtimes with Temma because it turned into something not weird but rather nourishing and comforting. I think about that when I look at this drawing: how alien things are just things you’re afraid to try.

Rachel Gonzalez is an artist living in Chicago.

Erica Ciganek

My first interaction with Temma was deeply moving. As a freshman in college I attended Temma’s 25th birthday party, which was held at a gallery filled with giant painting scale paintings of her. The evening consisted of music, stories, poetry. It was a celebration like no other I had attended. Then encountering her surrounded by the paintings was humbling.

When I first met her, there was this discomfort and lack of knowing how to encounter her. It began a time of re-visioning my limited understanding and history of interacting with people whose bodies and internal experience were different than my own.

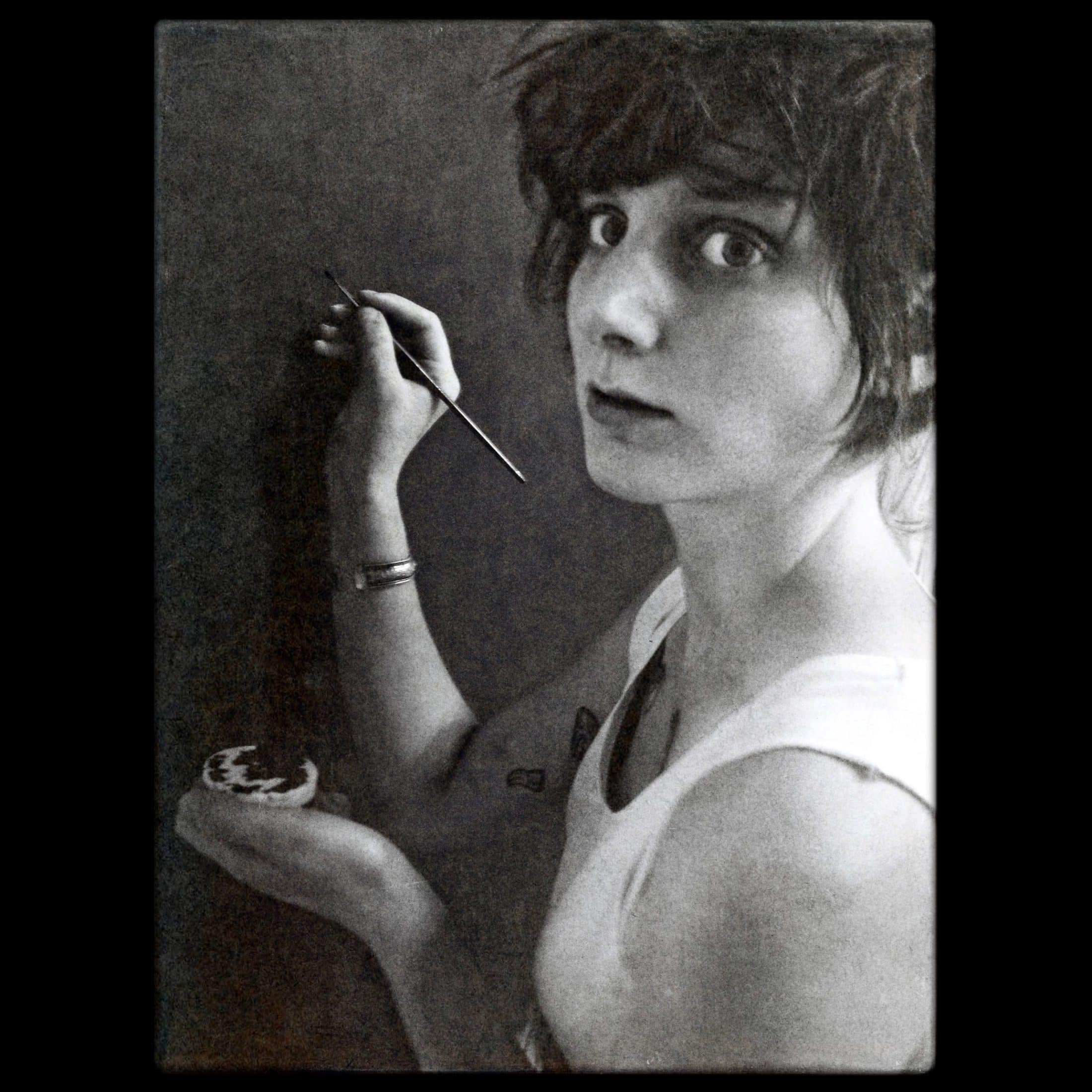

The chance to then paint Temma and learn from Tim’s painting of Temma has altered my life and my own creative practices. Seeing Tim’s place of humility that he always is trying to move into and work from has certainly been one of the main foundations of my work so far. There has been this pursuit of reverence and listening and waiting and watching in the process of making art.

Erica Ciganek is an artist and a member of Radiant Covenant Church in Renton, Washington

Maggie Hubbard

Prior to meeting the Lowlys I had nearly zero contact with those who are disabled or profoundly othered. I assumed life was harder when caring for one with disabilities, and I held somewhat of a fear of what that life would entail. But Tim and Sherrie’s relationship and care with Temma is one of the most profound acts of love that I have ever personally encountered. Their family exemplifies selfless care and community.

Tim has taught me so much of the life and spirit that one individual carries, and Temma has taught me about intimate presence. Through knowing Temma, even in such a distant and informal way, I have had my fears be transformed into awe.

Temma encourages me to rest, she slows me down, she invites me to see more deeply. This position of humility has transformed the way I approach subject matter in my own paintings as I find I resort to a similar place of reverence and service.

I depict everyday objects and places, like piles of books on a desk or a dimly lit dining room, all with the purpose of highlighting the otherworldly characteristics in those very worldly entities. There is a lot I would dismiss in my surroundings if it weren’t for this quiet and submissive approach that Temma has opened my eyes to.

Maggie Hubbard is an artist living in Chicago.

Jeanette Habash

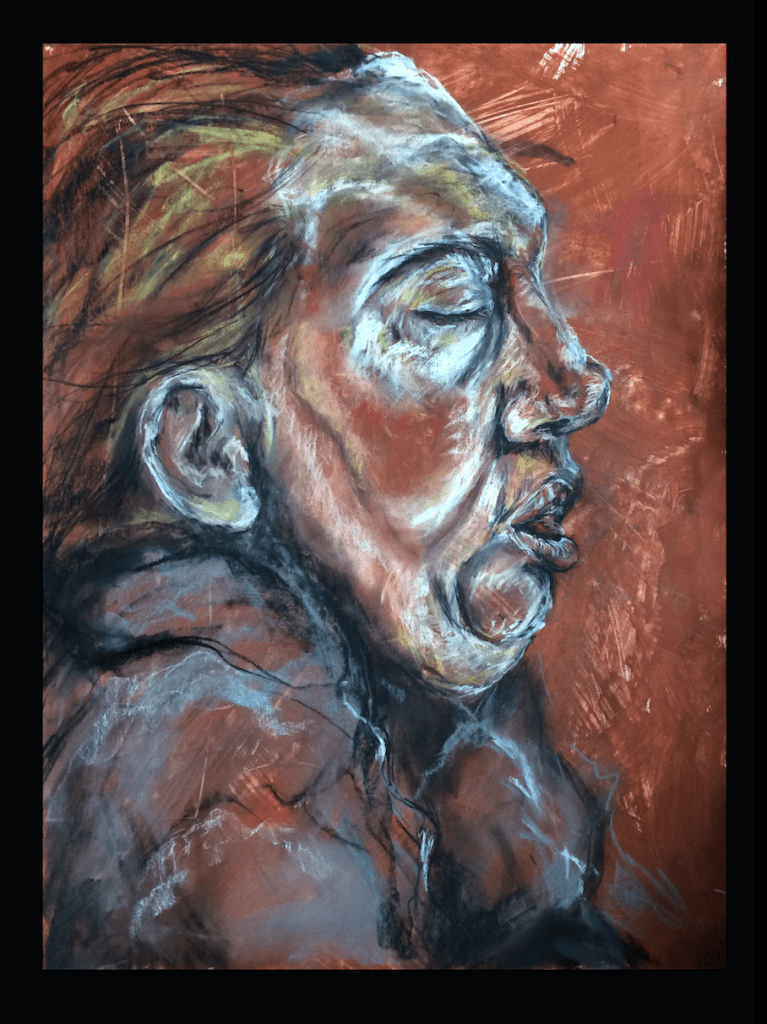

I think in the beginning when I was just drawing Temma, it was a very different experience because I had never encountered someone like her. I didn’t know whether I was doing something right or wrong. Obviously over time, the experience changed. I saw no difference between drawing Temma and drawing someone who is very unlike Temma even though she has a unique presence.

This experience with Temma has impacted how I see others with disabilities. She has a life and she lives it every day, showing up and being who she is.

When I’m sitting with her and spending time with her, I don’t have a direct line of connection. Neither of us can understand what the other is doing, but in that time when I’m drawing her, I’m engaged with her.

In the drawing of Temma in profile, I wanted to put forth the strong presence she has. I was moving quickly for two hours and was constantly looking at her while moving my wrist, never stopping to fix “mistakes” or make it perfect, but rather, capture her in the moment.

I tend to not worry about a clear image of someone. I tend to keep drawing and not trouble myself with the little things that might add up to a photographic image. So I tried to approach her as much as anyone else.

For me, drawing from life is always the best. I think there is a beauty in the struggle.

Jeanette Habash is an artist living in Chicago.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]