How Chaplains Are Holding Us Together

The silver band I wear on my wrist is engraved with words, from a prayer by Saint Teresa of Avila: His hands, his feet, his eyes of compassion. As a chaplain for a large secular medical center in California, I am asked not to wear a cross in my work with patients, families, and staff, out of respect for their different beliefs. I minister to Christians, Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists, Hmong, Sikhs, Jews, and atheists in our multicultural urban hospital. But the gentle pressure of the bracelet against my skin is a reminder that I follow Jesus into every patient’s room.

This calling has never felt truer than it does now. In the midst of the pandemic, chaplains have access to people and places other pastors do not. We minister from inside to a world that is hurting.

When a close friend had an unexpected heart attack and was admitted to our hospital intensive care unit a few months ago, I became her chaplain in the final week of her life. I sat with her and held her hand when the rest of her friends and family couldn’t enter the building due to Covid-19 restrictions. It was a heartbreaking honor.

When a young child was admitted to our pediatric ICU with a severe brain injury this fall, I prayed with his parents as they made agonizing decisions about his care without the support of extended family. I escorted them down the hospital hallway to the operating room when they donated his organs. A week later, I spoke at a sparsely attended memorial service to celebrate his short life. His parents thanked me for being there in the midst of their devastating loss.

I have also met with an increasing number of teenagers who have attempted suicide. Like many adults around them, they are struggling with anxiety and depression during this extended period of isolation. Some are also impacted by the rise in domestic violence and substance abuse during the pandemic quarantine. I hope I am a harbinger of hope to them.

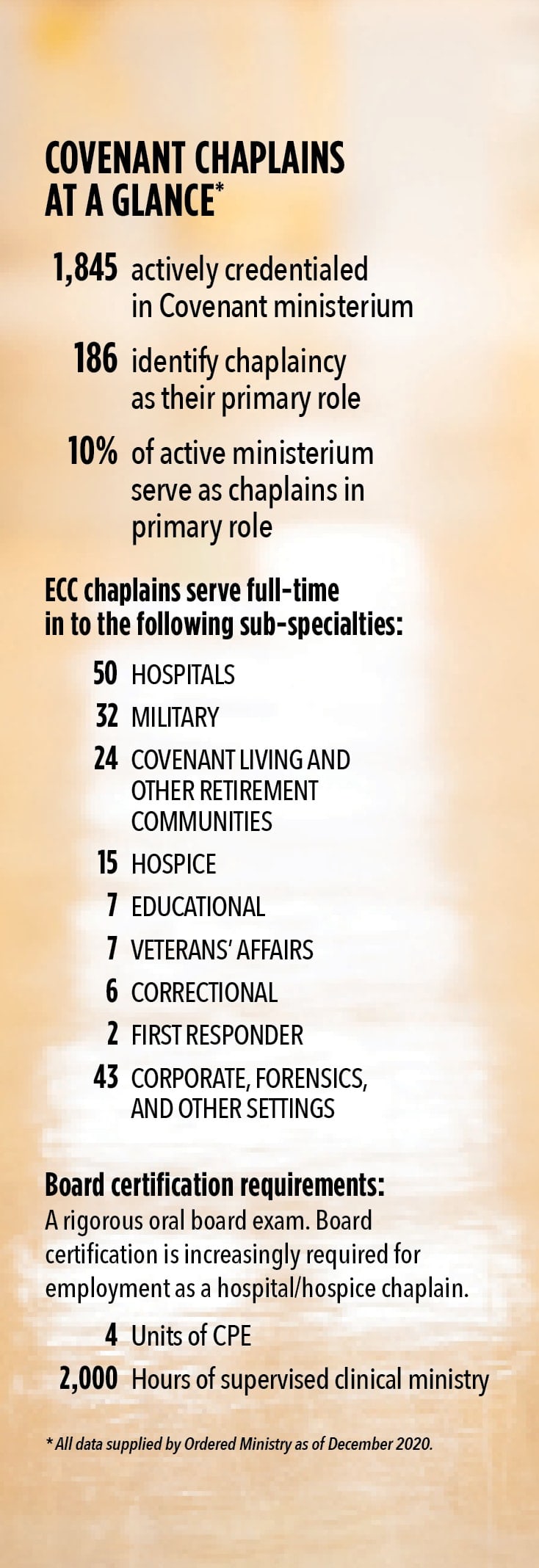

The past year has been a challenging one for chaplains who have continued to minister “on the front lines.” The Covenant has close to 250 chaplains serving full- and part-time in hospitals, hospice, prisons, education, the military, law enforcement, and senior living communities. Licensed, ordained, and endorsed in the Covenant Church, we go beyond the church walls to care for people who may not know God yet are loved by God.

While so many people have sheltered-in-place, chaplains have stepped forward as the hands and feet of Christ to people who are sick, dying, aging, imprisoned, or separated from loved ones due to military assignment or Covid-19 visitation restrictions. We have navigated rapidly changing demands and needs in the midst of the pandemic and social unrest, sometimes in the midst of our own personal crises.

On a recent Zoom call with Evangelical Covenant Church chaplains, Lance Davis, executive minister of Develop Leaders, said, “Many congregational pastors have felt their ministries restricted this year. But the role of our Covenant chaplains has expanded.”

Indeed, it has.

ALLISON WIBLE is a chaplain at Mercy Hospital in St. Louis, Missouri. She works primarily in the ICU and the burn ICU, which evolved into a Covid-19 ICU last year. She and her husband, Chad, who is also a Covenant pastor, have two children at home who are navigating online learning.

“Covid has rocked everything,” she says.

Like chaplains throughout the country, Wible must go through a daily screening process when she enters the hospital. She then dons a gown, gloves, mask, and face shield in order to work with patients, many of whom are in isolation due to their symptoms, and separated from their loved ones because of tightened visitation restrictions. While reaching out to families has become more complicated and time-consuming, Wible knows they need her support.

“The last thing we ever want is to separate families,” she says. “And yet for the health and common good, we are doing just that.”

Wible says she is grateful she and her team have been able to step into the gap for families who cannot be present with their loved ones.

“As with most of life,” Wible says, “there is grief intertwined with joy; there is isolation, and yet there is hope.“

She admits she often feels helpless. The nurses and doctors she works with feel the same. Exhausted staff members often turn to her for support.

“They are stretched and tired and ramping up to face another wave of Covid this winter. We talk about burnout and compassion fatigue,” Wible explains. “But what we are really talking about is grieving. Grieving the illness, grieving our hospital units feeling different, grieving our patients who die, grieving that things are not the way we wish they could be.”

“Holding a hand can be more powerful than a sermon.”

TRACY HILTS is a chaplain serving at Pikes Peak Hospice and Palliative Care in Colorado Springs, Colorado. In her 16 years as a chaplain, Hilts says the past year has been the most challenging because there are so many barriers to good care. She senses frustration in elderly patients with hearing loss who struggle to follow a conversation because of N-95 masks.

TRACY HILTS is a chaplain serving at Pikes Peak Hospice and Palliative Care in Colorado Springs, Colorado. In her 16 years as a chaplain, Hilts says the past year has been the most challenging because there are so many barriers to good care. She senses frustration in elderly patients with hearing loss who struggle to follow a conversation because of N-95 masks.

“The hardest thing I have had to do,” Hilts says, “is stand over a dying patient with an iPad while the patient’s family said their final goodbyes, unable to visit in person.” She worries about the lasting emotional impact.

“I’ve talked with many people who don’t know what to do with their complicated grief,” she laments. “They didn’t get to say goodbye. They can’t have a memorial service. Many people promise that their loved one will not die alone—and yet it happens.”

Hilts hopes her presence makes a difference.

“Being a chaplain is about being in the moment,” she says. “Whatever that moment looks like. I’m trying to represent the compassion of the Father, the love of Jesus, and the sufficiency of the Holy Spirit. Holding a hand can be more powerful than a sermon.”

CAMERON WU-CARDONA works at Heartland Hospice in the San Francisco Bay area. He recently completed his Clinical Pastoral Education (CPE) at UCSF Medical Center. A yearlong residency, typically done post-seminary, is required in order to become a board-certified chaplain. Wu-Cardona made a vocational shift after an 11-year pastorate in congregational ministry. He was just beginning his training at UCSF when Covid-19 began to spread. He describes his ministry transition as difficult but profound.

“It pushes me to my limits,” he admits. “At times, all I can do is lament the state of the world. But I know that such lament presses me to seek and find the God who cries out with us.”

In the pediatric ICU where he did his clinical work during CPE, Wu-Cardona admits he sometimes struggled to maintain a balance between adhering to hospital protocol and advocating for the needs of patients and families. As a father and husband, he recognizes the importance of the bond between parents and their children and tries to be creative through the use of tele-health options, such as phone calls and FaceTime.

While Wu-Cardona is grateful for his CPE experience and his current work in hospice, he has found chaplaincy to be both painful and holy.

“The sacred act of holding space for those facing death is a multifaceted role of providing a compassionate presence, embodying love, eliciting courage, and bearing witness to what is ultimately a sacred journey we all will face at some point.”

Despite the honor of being with the dying, Wu-Cardona acknowledges that witnessing families experience personal loss on top of the global pandemic, racial tension, and political instability of the past year has pushed many to the brink. Yet he is inspired by his patients. “They provide me with perspective to remain courageous and grounded,” he explains.

“I’ve often felt like I’ve had so little to give.”

Across the country, CORRIE MONTOYA serves as associate chaplain at Covenant Living of Florida, an assisted-living community serving the greater Fort Lauderdale area. She says 2020 brought a massive switch and overhaul to her work.

When the pandemic shut down all in-person programs and gatherings serving their vulnerable senior population, Montoya says her team quickly adjusted so that morning prayer, fitness classes, bingo, and worship services could all be available to residents via TV broadcast.

“What helped me adapt and bring energy to chapel was picturing our residents in their homes,” Montoya says. “Seeing them, at least in my imagination, helped me focus on bringing the Word with as much life as if the residents were in the room with us.”

Montoya experienced a season of transition and turmoil firsthand last year.

“The pandemic’s impact on my personal life has been immense,” she shares. “My husband and I eloped on February 22, and about three weeks later, South Florida shut down. We are both considered essential workers, so we continued reporting to work amid a lot of uncertainty.”

Then, Corrie’s husband, Dennis, suffered a major back injury and had surgery in May. The day of his surgery, Corrie had a miscarriage. A short time later, she needed an emergency appendectomy. She has experienced impacts of the pandemic from all sides—as a patient, family member, and chaplain.

“We’ve had to navigate these unexpected hospitalizations during the pandemic, which meant we could not be with one another,” she explains. “In the midst of all this, I’ve been expected to be a leader on our campus, specifically as a chaplain, to help residents and staff find peace in the midst of chaos and uncertainty. I’ve often felt like I’ve had so little to give.”

Montoya admits the limited social interaction has been difficult for her. She describes herself as a strong extrovert who gains most of her energy from spending quality time with others. The lack of human contact has led her to develop new self-care strategies to gain energy and remain positive.

“My husband and I have taken up the practice of sharing one, good, long, secure hug every day after work,” she says. “This hug stands in the place of all the hugs, handshakes, high fives, and fist bumps we would normally receive from friends and coworkers. The hug helps us take deeper breaths and our bodies release stress we’ve been carrying throughout the day.”

“Despite the beeping and blipping of the medical equipment around me, I am called to provide pastoral care to the hurting and infirm.”

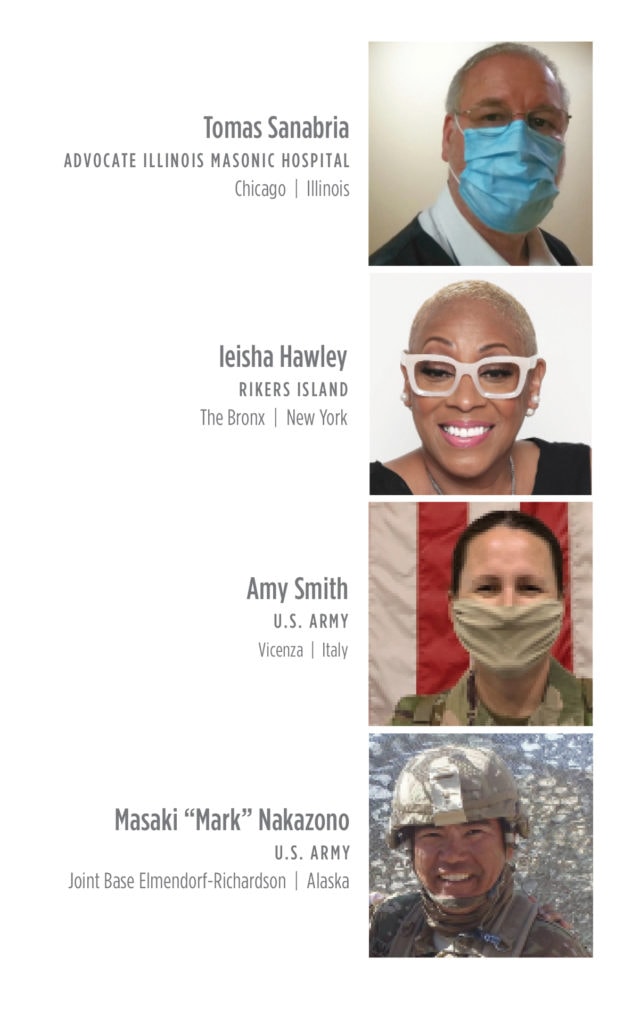

TOMAS SANABRIA is an associate chaplain at Advocate Illinois Masonic Hospital, a major trauma hospital in Chicago. He also serves as full-time pastor of the Spanish-speaking church, Iglesia del Pacto Evangélico de Albany Park, where several members of his congregation have contracted Covid-19. Sanabria has also lost family to the disease. Despite the stresses and challenges of the pandemic, the bivocational pastor says he feels called to be both an essential faith worker and a community pastor.

TOMAS SANABRIA is an associate chaplain at Advocate Illinois Masonic Hospital, a major trauma hospital in Chicago. He also serves as full-time pastor of the Spanish-speaking church, Iglesia del Pacto Evangélico de Albany Park, where several members of his congregation have contracted Covid-19. Sanabria has also lost family to the disease. Despite the stresses and challenges of the pandemic, the bivocational pastor says he feels called to be both an essential faith worker and a community pastor.

“Both are ministries in which faith and heart are challenged,” he explains, “where an adverse moment can make you cry.”

He admits he is often overwhelmed with emotion in his work at the hospital, where he feels fear and gratitude at the same time.

He visited one Covid-19 patient three different times, suiting up in PPE to pray with her in her room. After their last prayer session, Sanabria says he sensed the full weight of what he had taken on, just so the patient could hear and see him.

Leaving the patient’s room, Sanabria recalls meticulously taking off the protective medical coverings he had put on 20 minutes earlier: the surgical shoe coverings, hair mesh, N-95 mask, gloves, plastic face covering, and a surgical gown.

“Despite the beeping and blipping of the medical equipment around me,” he says, “I am called to provide pastoral care to the hurting and infirm.”

“I had to pray as I drove over that bridge, but I knew I was on assignment, and that assignment was from God.”

IEISHA HAWLEY also knows what it’s like to feel at risk. Initially, Hawley was a palliative and hospice care chaplain, but says she felt led to go into prison chaplaincy two years ago. She now serves as chaplain at Rikers Island in New York, a complex of jails and prisons in the Bronx.

“It is a joy to bring compassion and the gospel to God’s beloved who are inmates and corrections staff,” she says.

When the pandemic infiltrated their system, with prisoners and guards getting sick, Hawley’s already challenging work became even more complicated. She recalls the chaos of being an essential employee in the early weeks of the pandemic.

“There were so many uncertainties and unknowns,” she remembers, “and we had to take a chance with minimal equipment and face masks. We were scrambling to figure out how to do our jobs and keep ourselves safe.”

Hawley recalls driving over the bridge from Queens to Riker’s Island to begin her shift. She admits she felt worried about how high the number of Covid cases might be, whether or not she would contract the virus, and how her exposure could affect her family. But she says she was determined to put faith over fear.

“I had to pray as I drove over that bridge,” she acknowledges, “but I knew I was on assignment, and that assignment was from God.”

Hawley describes a chaplain as “a pastor with a superhero suit on.” She needed that sense of power as she served in ministry while also caring for her mother, who was struggling with multiple myeloma and then contracted coronavirus, which exacerbated her cancer. Hawley supported her mother through several rounds of excruciating chemo treatments and a stem-cell transplant before finally taking her home on hospice in November.

“I had a lot of people holding me in these spaces,” she says. “My family, colleagues, and other Covenant chaplains and pastors who undergirded me. I also know when to raise the white flag when I am exhausted and need to take a rest.”

Despite precautions, Hawley tested positive with Covid-19 and ended up spending Thanksgiving in self-quarantine.

Hawley cites Parker Palmer as a source of inspiration for her ministry: “The deeper our faith, the more doubt we must endure; the deeper our hope, the more prone we are to despair; the deeper our love, the more pain its loss will bring: these are a few of the paradoxes we must hold as human beings. If we refuse to hold them in the hopes of living without doubt, despair, and pain, we also find ourselves living without faith, hope, and love.”

AMY SMITH has been serving as an active duty Army chaplain at Fort Drum, in New York, for the past three years. She is making a permanent change of station to Italy this January to serve as battalion chaplain.

Smith says the concept of a ministry of presence––often used to describe the role of a chaplain––has taken on new meaning for her during Covid. She increased her online presence with soldiers and reached out by phone and texts when she would normally prefer to connect in person.

“What I have come to realize,” she says, “is I am still able to be present with soldiers and their families during a phone call or video chat, and the Holy Spirit still works through technology.”

Smith has observed soldiers increasingly struggling with depression, anxiety, and loneliness after months of stay-at-home orders. She knows they have sometimes wondered if they will ever see their loved ones again.

“Most soldiers are stationed away from family, and really the only time they can see them is when they take leave, which is not often,” Smith explains. Travel restrictions have prevented many from going home, even for the holidays.

“I recognize I can’t take away their sadness,” Smith admits, “but I can point them to the message of hope that is found in Jesus.” She says she also encourages soldiers to respond to the needs of others around them who may be struggling.

“My hope is they will examine and respond to the needs of those they live next to, as well as those they serve alongside,” Smith says. “Serving one another strengthens the bonds of community and spreads the message of love. God is bigger than Covid.”

When our soldiers and families experience their greatest darkness, we are called to be a light to them, shining the way toward hope.

MASAKI “MARK” NAKAZONO is also a chaplain in the United States Army. A lieutenant colonel, he took on the role of command chaplain at Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson in Alaska last July.

Nakazono acknowledges that providing senior level leadership and chaplain care across such a vast state is both challenging and compelling.

“I find myself thriving in an environment with volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous conditions,” he says. “I depend on the Lord to help me remain steadfast and sure-footed in my character and rely on him to continually give me courage that is fostered through faith in him and not my own strength.”

Nakazono appreciates the unique opportunities his role provides.

“It is hard to compare the job of a chaplain to any other job, even within our religious profession,” he says. “Imagine any other non-religious organization that supports religious clergy walking among its workers to share God’s love and presence on a daily basis. In the days when our soldiers and families experience their greatest times of darkness, we are called to be a light to them shining the way toward hope.”

Nakazono says he is grateful for his many years in the military, as well as his ongoing ties to the denomination.

“The longer I serve in uniform,” he says, “the more I cherish my Covenant relationships and my foundation in faith with my Covenant family. My passion to serve stays grounded in my early calling as a Covenant pastor.”

Connection to the Covenant is an important lifeline for chaplains who face ongoing challenges in their varied ministries. Despite their courage and commitment, the risk of compassion fatigue, moral distress, and burnout is high as they often work alone in stressful circumstances, face ongoing trauma and crisis, and are without the support of colleagues who share their Christian faith.

The Covenant Chaplains Association (CCA) works to provide support and a sense of connection to assist chaplains in every conference and context to be resilient. Two webinars on resilience were well attended last fall, and a new Thriving in Ministry cohort for chaplains begins in January, under the direction of Herb Frost, director of vocational and spiritual development with Develop Leaders. CCA also hosts regular Zoom calls with Evangelical Covenant Church president John Wenrich, allowing chaplains throughout the denomination to share their stories and connect with one another and with Covenant leaders.

“I am blessed by a deeper appreciation and relationship with our Covenant chaplains,” Wenrich says. “I have enjoyed our conversations and am inspired by their courageous commitment to proclaiming and demonstrating the whole gospel.”

On a recent CCA call, a military chaplain offered to pray for the hospital chaplains.

“We are all part of one body,” he acknowledged. “And we need to support one another. Military chaplains are used to being on the front lines. But now, we are all there together.”