Covenant Pastor Bill Stephens Helps Lead Recovery Efforts After Colorado Fires

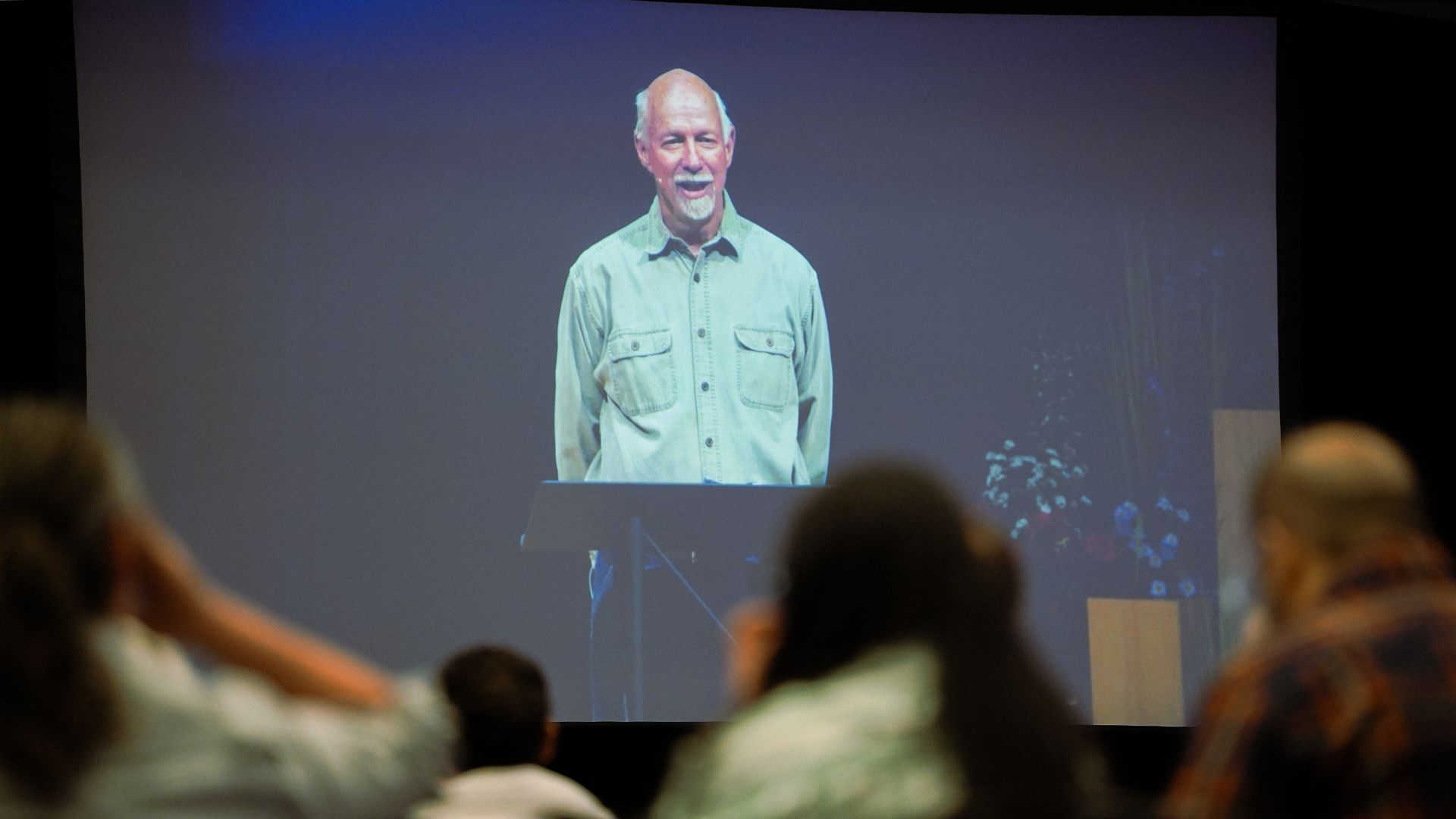

Bill Stephens was so choked up he could barely get the words out. Standing on the platform, he recited these words from Every Moment Holy, a liturgy dedicated to those suffering loss from fire—and was overwhelmed with gratitude.

“We were shaped by this place, and by the living of our lives in it, by conversations and labors and studies, by meals prepared and shared, by love incarnated in a thousand small actions that became as permanent a part of this structure as any nail or wire or plank of wood.”

– Douglas McKelvey

Stephens serves as pastor of Ascent Community Church in Louisville, Colorado. On Sunday, January 2, the congregation was forced to move their worship to the Omni Hotel in nearby Broomfield. The most destructive fire in Colorado history had raged through their county two days earlier, destroying nearly a thousand homes and damaging hundreds of others. And though Stephens and Louisville police chief Dave Hayes were helping to lead the recovery effort, their hearts were heavy—not just from the collective trauma, but from their own losses. Like dozens of others in their community, both men lost their homes to the fire.

Returning to Omni “was like coming full circle,” said Stephens as we spoke over the phone. The Omni Hotel was the place where Ascent held its first services when it was planted more than eight years ago.

“We wanted to be a presence in the community,” said Stephens. “That was a vision of ours from the beginning.” That presence included intentional relationship-building with local officials and community stakeholders, including several school principals, city representatives, and Chief Hayes.

So as both church folks and local police mobilized in the fire’s immediate aftermath, the institutional collaboration was an outflow of the partnership Hayes and Stephens had been cultivating for years, sharing resources and personnel. They’d worked together on annual Christmas toy drives that a local officer spearheaded. Police and other government agencies often used the Ascent Community Church building for gatherings.

When the fire came just short of burning down Ascent’s building, all the officers who responded already knew the church property, and church staff knew them all by name. When the city needed to help distribute passes for local residents to return to and from their homes without having to show ID, teaming up with the church was a no-brainer.

Both Stephens and Hayes are doing their best to model authentic relational connection in the context of tragedy.

“We’re both in caregiving positions,” said Stephens, “but we still gotta take care of our own.” He recounted a recent afternoon when they both had a moment together to exhale and share a hug. “I didn’t know which one of us was going to let go first,” he said. “We just felt each other’s pain and held each other. We both felt like we had to be strong for each other.”

According to Stephens, there are layers to the loss.

“The first level is the sentimental value of pictures, wedding videos, and the like. It’s a punch to the gut, and you put it to the side, so it doesn’t bring you to your knees. Other losses come gradually as you remember certain things that were in the home and think, ‘Oh, that was in there too.’”

But the final layer is as overwhelming as it is inescapable.

“That level is just the sheer gravity of starting over. It’s walking into a Target or a Wal-Mart and knowing that you have to walk down every aisle.” Weeks later, Stephens marvels at the sheer breadth of tasks in front of him. “You have to tow a burned-out car out of your driveway, and you have to deal with homeowner insurance, and you have to deal with a construction and repair industry crippled not only by the pandemic but also supply chain issues.”

Stephens admits that he used to regard such tragedies with typical platitudes.

“‘’That’s why there’s insurance,’ I would think. ‘They’re just earthly treasures.’ What I didn’t realize until I started to go through this is that the things we have in our home—the mementos and homemade stuff—those are heavenly treasures. They speak to us about the reality of our heavenly home. My daughter said to me, ‘It’s not the couch I’ll miss—it’s the living room I’ll miss.’”

As he considers the prospect of rebuilding, Stephens is circumspect. “You can’t really tell until you’re in the heart of it, but every one of us in ministry positions eventually has to answer the question, ‘Do I have a faith that’s going to stand, and am I really going to trust the Lord?’”

Answering his own question, Stephens continues, “I lean so heavily on the goodness of God. God has met us and is meeting us, and the outpouring of love is a gift from the Lord. I’m so thankful for what the Lord is doing in the midst of this trauma.”

The written liturgy concludes:

Shepherd us, O Lord, as we wake each new morning, faced with the burdens of a hard pilgrimage we would not have chosen. But as this is now our path, let us walk it in faith, and let us walk it bravely, knowing that you go always before us. Amen.

About the Author

Jelani Greenidge is the missional storyteller for the Evangelical Covenant Church. He’s also a hip-hop vocalist and producer, DJ, stand-up comic, and serves as the worship pastor for Access Covenant Church in Portland, Oregon.