Recognizing Ourselves in Our Own Narrative

Excerpted and adapted from Struggling with Evangelicalism: Why I Want to Leave and What It Takes to Stay, by Dan Stringer

When I was a young child, my parents read me a book called Are You My Mother? The story opens with a baby bird hatching from an egg while his mother is out finding food. Not knowing what his mother looks like, the hatchling waddles right past her. In successive encounters with a kitten, a dog, and a cow, the little bird asks, “Are you my mother?” To his dismay, they all reply “no.” Increasingly discouraged, the little bird begins to wonder if he even has a mother.

With escalating desperation, he calls out to a boat, an airplane, and even an enormous power shovel, declaring, “Here I am, Mother,” but no one answers. Finally, the power shovel drops him back into the nest, just as his mother returns and asks, “Do you know who I am?” The baby bird replies, “Yes, I know who you are. You are not a kitten. You are not a dog. You are not a cow. You are a bird, and you are my mother.”

It might surprise some American Christians that 82 percent of the world’s evangelicals live outside the United States.

This heartwarming story centers on the search for a parent, but it’s also a quest for identity. Until the baby bird knows who his mother is, he doesn’t know who he is. Had he realized he was a bird, he would not have asked the other animals if they were his mother. Without an accurate self-understanding, he looks for belonging among boats, airplanes, and power shovels. The hatchling is not just looking for his mother; he is looking for his identity.

Like baby birds waddling from the nest, evangelicals sometimes don’t know which species of Christian they are. They might identify broadly as Christian but don’t see themselves belonging to the evangelical category. Lacking awareness of who laid the egg from which they hatched, they don’t realize that evangelicalism is their mother. Like the bird who hatched while Mama was away, they walk right past their evangelical parents and siblings without recognizing them as family. When they hear the word “evangelical” used to describe something negative or narrow-minded, they think, “That’s not me!”

When my college roommate interviewed for medical school, the interviewer asked why he chose Wheaton for his undergraduate studies. His response: “Because I wanted to receive the best Christian education I could.” To which the interviewer replied, “What about Notre Dame?” At this point, my roommate realized he had used the word “Christian” as a synonym for evangelical, as many American evangelicals do. Evangelicals tend not to think of Catholic universities such as Notre Dame as Christian schools because we actually mean “evangelical” when we say “Christian.” The prevalence of evangelical Christianity in the United States allows us to get away with imprecision.

Christians in the World

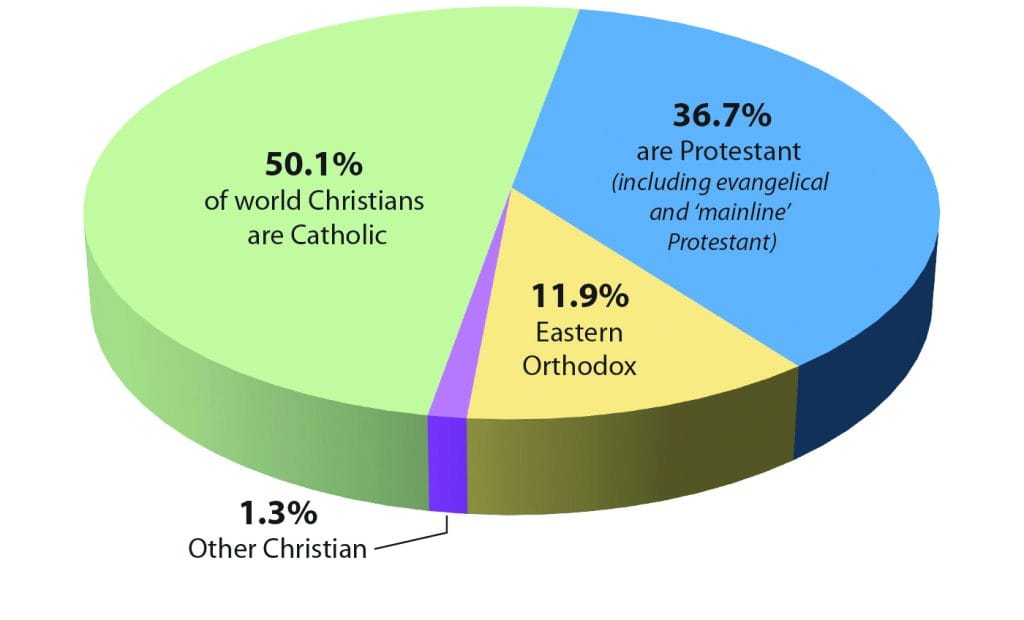

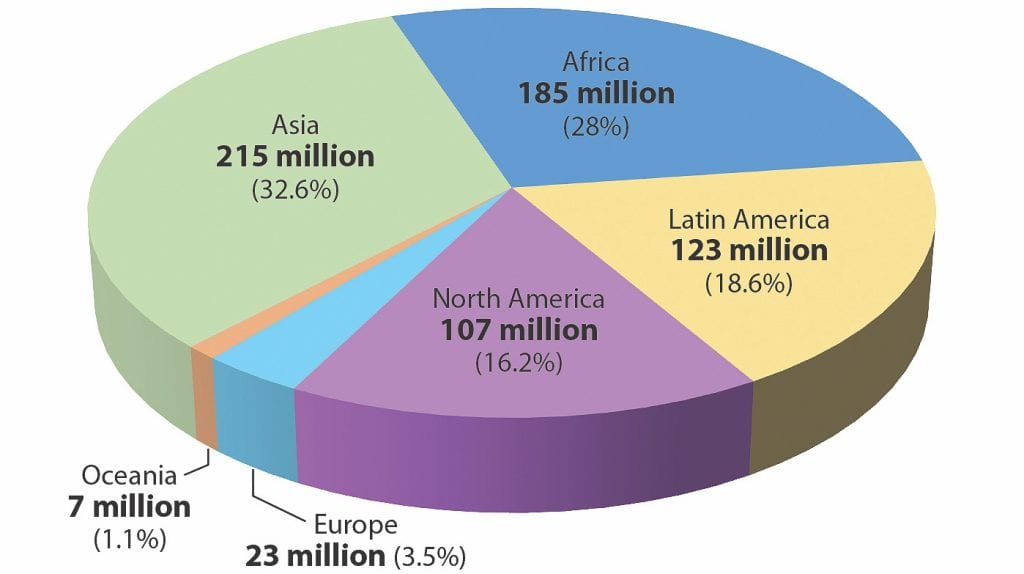

This lack of clarity has downsides. First, it confuses a larger category (Christian) with a smaller category (evangelical Protestant). The majority of Christians in the world are not Protestants, much less evangelical Protestants (see figure 1). Furthermore, three in five evangelicals live in Asia or Africa, whereas less than one in five live in North America (see figure 2).

GLOBAL EVANGELICALS

Second, it fails to acknowledge evangelicalism’s particularity within Christianity. Evangelical norms such as informal extemporaneous prayer (“Good morning, Lord”) are taken for granted as the Christian standard, and thus are simply deemed “prayer” without an adjective, whereas non-evangelical styles of prayer are given modifiers such as contemplative prayer or liturgical prayer. Third, conflating evangelicalism with Christianity claims supremacy for our movement at the expense of other expressions of Christianity, as if evangelicals have a monopoly on Jesus. If we take seriously the body of Christ’s diversity worldwide, neither Christian nor Protestant are specific enough terms to identify our particular faith stream. Perhaps the dreaded e-word is more indispensable than we thought!

As a result, we evangelicals end up centering ourselves (whether consciously or not) and marginalizing other people of faith. We claim a monopoly that isn’t ours, judging others to be “less Christian” when they don’t look like us. We can cause damage when we operate under an assumption that our culture is the default. But our vantage point is just that: a location from which we view everything else.

As a Hawai’i-born child of medical missionaries, I grew up in five countries on three continents—largely due to my parents’ evangelical faith. When I was seven, we moved from Mililani, Hawai’i, to Jonquière, Quebec, for an immersion year of learning French. We spent the next three years living in Kananga, Zaïre, followed by 18 months back in Hawai’i, then a six-month stint in Kentucky before relocating to Kathmandu, Nepal, for six years. During the last three of those years, I attended Faith Academy, an interdenominational, evangelical boarding school in Manila, Philippines.

My nomadic upbringing taught me that evangelical churches don’t all worship God in the same way or reach the same conclusions when interpreting the Bible. But they all expect Jesus to make a difference in their lives. Evangelicals in Nepal worship Jesus with different emphases than evangelicals in the United States. Evangelical churches in the Congo preach from the Bible with different assumptions than evangelical churches in the Philippines. As I realized the power of location to shape ideas and expectations, I came to see evangelicalism less as a brand and more as a space. A brand is what you buy, but a space is where you live. Switching brands might change how you look or it might alter your shopping habits, but changing homes can impact every area of life—especially when moving from one continent to another.

I came to see evangelicalism less as a brand and more as a space. A brand is what you buy, but a space is where you live.

When Lifeway Research surveyed the differences between those who call themselves evangelicals and those who hold evangelical beliefs in 2017, they found a gap. More Americans self-identify as evangelicals (24%) than strongly agree with evangelical beliefs (15%). At the same time, only two-thirds (69%) of evangelicals by belief self-identify as evangelicals. If 31 percent of American evangelical believers reject the label, it’s no surprise that other terms are used when self-identifying one’s faith. In fact, it’s perfectly possible to love Jesus, read the Bible, and belong to a church with evangelical beliefs without ever self-identifying with more precision than “Christian.” By denying the brand without leaving the space, you can be part of evangelicalism’s demographics (quantifiable traits of a population that can be observed from the outside) without necessarily conforming to its psychographics (internal motives and values that drive behavior).

Depending on the survey, evangelicals make up somewhere between 16 and 29 percent of the U.S. population, according to Evangelicals Around the World: A Global Handbook for the 21st Century. Even if we estimated on the high end (29%), this translates to 97.5 million evangelicals in a population of 330 million people. At first glance, 97.5 million seems like a big number, but that’s only 18 percent of the world’s 545.9 million evangelicals according to Operation World. It might surprise some American Christians that 82 percent of the world’s evangelicals live outside the United States.

When accounting for Catholics, mainline Protestants, and Eastern Orthodox believers, we see that Christianity is much bigger than evangelicalism. The Pew Research Center estimates the global population of Christians at 2.4 billion. If we use Operation World’s estimate of 545.9 million global evangelicals, that means less than one-fourth (23%) of the world’s Christians are evangelicals. Based on these numbers, American evangelicals are just 4 percent of the global body of Christ, with less than 3 percent being white.

Despite spending ten years of my childhood outside the United States, I still slip into assuming that white Americans constitute evangelicalism’s center. Amid all the attention given to white evangelicals in political reporting, it’s notable that one-third of American evangelicals are people of color, including nearly half of evangelicals under age 30, according to “One in Three American Evangelicals Is a Person of Color,” by Sarah Eekhoff Zylstra (Christianity Today, September 2017). Twenty-two percent of young evangelical Protestants are Black, 18 percent are Hispanic, and 9 percent identify as some other race or mixed race. Only 50 percent of evangelical Protestants under the age of 30 are white, compared to more than three-quarters (77%) of evangelical Protestant seniors (age 65 or older).

What makes a space evangelical? I’ve come to see evangelicalism primarily as the zip code of our spiritual habitat. It’s where we’re located on the map of Christianity. You don’t have to identify with the evangelical brand to live here, any more than one has to identify with the bald eagle and Uncle Sam to inhabit the United States. Like any neighborhood, there are pros and cons to living here. Like any habitat, it can be a healthy place to flourish or a toxic place that drains life.

Evangelicalism not only fosters shared beliefs, it creates shared experiences that make it identifiable as a distinct culture with its own vocabulary. That’s why so many of us know what it means to “stand in the gap,” “be on fire for God,” or pray for “a hedge of protection.” And if you don’t know how to do popcorn prayers, share praise reports, or love on people, you’ll be fine if you keep pressing in. Just let go and let God!

Once we see evangelicalism as a shared space more than a brand, we start noticing how its living conditions impact residents. When a neighborhood’s crime rate spikes or water supply becomes contaminated, concerned residents take action on behalf of their community instead of calling it someone else’s responsibility or waiting for things to get worse. Like any place, evangelicalism has its fair share of problems and unhealthy patterns that disproportionately harm residents on the margins. Call it our “baggage.” Every religious group has baggage, but when we fail to own ours, things get worse. Our aversion to the evangelical label can make it harder to own our baggage. It’s much easier to shout advice from a safe distance than participate in a messy cleanup.

Since the well-being of evangelicalism’s residents matters to God, it’s for our neighbors’ sake that we strive to improve conditions impacting both current and future community members who follow Jesus here. We won’t solve evangelicalism’s problems overnight, but what if this were a more gracious, sustainable, just, and spiritually healthy place to live? I believe God is calling evangelicals to own our own baggage, accepting that we have failed in significant ways while still possessing something incredibly life-giving to offer.

One of our historic mottos as Covenanters is to live intentionally “for God’s glory and neighbor’s good.” Despite my uneasiness with much of what North American evangelicalism has become known for, I have a responsibility that comes with living here. I was born here, work here, and raise my kids here. Many dearly loved ones still live here. It’s our spiritual home, the place where we met Jesus and became his disciples. I care about what happens in my religious neighborhood, which is why I want to leave this place better than I found it.

Imagine the impact of a renewed evangelicalism. Instead of assuming centrality for ourselves, we would acknowledge our unique faith stream, baggage and all. A renewed evangelicalism marked by true repentance wouldn’t just say the right thing, but would embrace the whole of Jesus’s gospel. In a renewed evangelicalism, his followers would boldly name the idolatries and injustices that plague our spiritual home and take meaningful steps to make things right. A healthier, less toxic evangelicalism means more hope and spiritual resilience overall.

Make no mistake: there’s a big mess to clean up in North American evangelicalism, but it starts with admitting we live here.

Adapted from Struggling with Evangelicalism by Dan Stringer. Copyright (c) 2021 by Daniel Stringer. Published by InterVarsity Press, Downers Grove, IL.

Figure 1: Pew Research Center, “Orthodox Christianity in the 21st Century,” November 8, 2017.

Figure 2: Lifeway Research, “3 in 5 Evangelicals Live in Asia or Africa,” March 2, 2020.