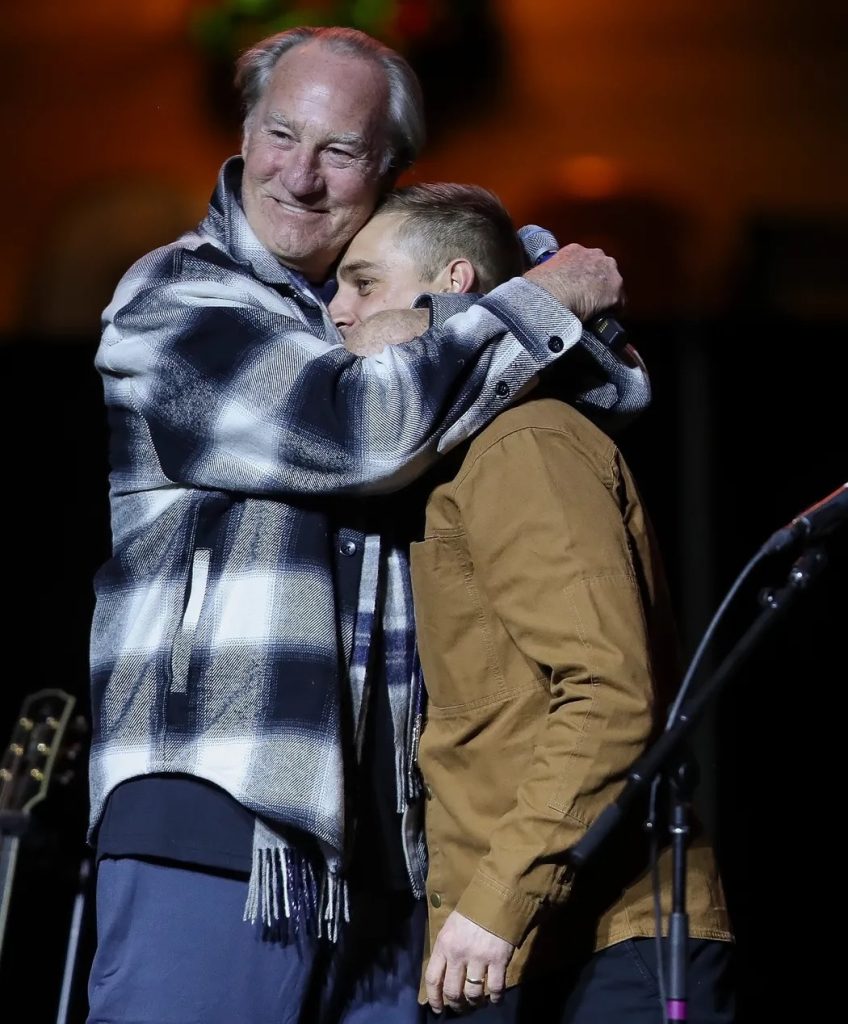

Siblings Anders and Davin Lindwall grew up in Covenant household, attending Grace Covenant Church in Iron River, Michigan. We sat down with them to talk about their debut feature film, Green and Gold, which depicts Wisconsin dairy farmer Buck (Craig T. Nelson) who faces bankruptcy and risks it all to bet on his beloved Green Bay Packers. Also starring Madison Lawlor, the film is streaming now. This conversation was edited for length and clarity.

As you were growing up, were you both always into the idea of making creative films? or did something about this story prompt you into action?

ANDERS: We’ve always been making videos. In high school we had a teacher who really ignited us, basically opening the school in the summer and on the weekends to let us edit and shoot videos. We were making all kinds of goofy stuff—ski films, Davin was making rap videos. This kind of creative work came naturally for us.

We make commercials as our day job, which is like shifting movie-making into a thirty-second experience. So there was a lot of natural overflow, but this was our first opportunity to play “pro ball.”

We’d been pitching stories for a while. These projects are super high risk from an investment standpoint, so you’re trying to think about what’s a good strategic move that’s not gonna flush people’s money down the drain. They say that 80 percent of movies lose money, 10 percent break even, and the other 10 percent is supposed to pay for the rest of the movies that get made.

For a while, I worked with the filmmaker M. Night Shyamalan in Philadelphia, and he always said you have to tell stories. He knew that we were from the Midwest, and he told me, “You’re from such a unique part of the world. When you get a chance to do your own film, find something as close to home as you can get, and shoot that.”

So for Davin and me, this project is about as close to home as we could get. Our grandfather was a dairy farmer, and we grew up knowing a lot about that kind of agrarian life. Our cousins were really involved with Future Farmers of America. So we really wanted a story that accurately portrayed rural America and that spirit of community benevolence.

And then we found a way to write the Packers into it, and we figured that’s a great audience that hasn’t really had a story about them, and away we went.

How long did it take from start to finish?

ANDERS: It was about a five-and-a-half-year journey to theatrical release, and then a few more months to get it into streaming.

What was it like working together as brothers on this film?

DAVIN: I’m a producer, and Anders is a director and writer. In the independent film space, those titles dissipate pretty quickly—you end up sharing roles since you don’t have the means to keep everybody in one category. But we’ve always been pretty collaborative as brothers. That’s one of our strengths—that we care for each other very deeply and we honor each person’s ideas.

So Anders led most of the creative direction of the story as the director, but he overlapped quite a bit in the producing and onboarded some of our bigger marketing contacts on the back end. This being an independent film and our first feature, we both had to wear a lot of different hats.

My role up front in the early days of production involved moving to Wisconsin and getting to know local farmers and our local contacts. That was one of our better moves early on—to embed ourselves in the location where we were going to shoot. We had roots in that area already, so that helped, but becoming local helped us to speak the same language and learn some of the nuances and the cultural norms.

You both have kids, right? You uprooted your family for this?

DAVIN: The timing worked out really well because both of our kids were super young. We each had one kid at the time, so the timing worked out well to uproot our family for a six- to eight-month stretch.

What was it like pitching this story to the Packers? How do you get an NFL team on board an indie film like this?

ANDERS: It was tough. When we had our first draft of the script, our entertainment lawyer said, “Just so you know, you might be getting a cease-and-desist from the NFL on this project. You are right on the edge.” And we were like, “Okay, cool, good to know.”

But it never came down to that. It helped when we got LeRoy Butler onboard—he’s a Hall of Fame former Packers player who does a cameo in the film. He watched an early cut and really liked it, so he wrote this really nice letter to the NFL on our behalf. And NFL Films told us that this was the kind of content they wanted to be associated with, so they donated a huge amount of classic Packers footage, which we were able to use in the film for a fraction of the cost.

But actually getting the Packers on board was a lot harder. Initially, we were going to try to do the world’s largest movie premiere and show it at Lambeau Field, but they said, “We’ll need three million dollars.” We knew there was no chance of that happening!

At some point, their lawyer called us. Our working title originally was God Loves the Green Bay Packers, and she asked, “How set are you on calling it that? We’d love it if you could change it to something else.” We were open to just about anything at that point, so that’s how we ended up with the title Green and Gold.

Even though we had a background in making commercials, we didn’t really know much about sports marketing or corporate sponsorships. It took about two years of emailing people and trying to get the conversations going. One day I emailed the Packers Foundation, and they connected me to one of their corporate partners. Through their help, we were able to turn this film into a corporate sponsorship, rather than just an indie film that’s just trying to use the Packers in their movie. By that point, we’d already gotten Culver’s on board, and they’re one of the Packers’ existing partners.

So instead of seeing us as a parasite trying to feed off of them, the foundation saw us as something that could really serve their brand. That’s what it took to get them to catch the spirit of what we were trying to do. It was a real roller coaster. They really protect the brand.

Would you call this a faith-based film? Do labels like that tend to help or harm projects like yours?

DAVIN: I’m hesitant to label it faith-based, because of how faith-based films have been treated historically—how they’ve been made and how the industry views them. There are a lot of connotations with that.

Our vision was never to make an evangelizing film. But it is faith-based in the sense that Anders and I grew up in this tradition, we still practice it and believe in it and teach it to our kids. There are so many elements of our faith that are infused into the way we live—taking care of our neighbors, taking care of animals, and showing care for the environment. But I’m hesitant to label it that way myself.

ANDERS: One pretty big faith-based theatrical distributor didn’t go with our project because it wasn’t faith-based enough. It’s such a tricky category because it’s not like this is “just” a sports movie. But when you’re talking about the spiritual life, you have to navigate which things are considered spiritual content from a storytelling perspective. There’s so much of my spiritual life that is deep and rich and important. And I don’t need to have a Hillsong song behind it to amplify those aspects. Our faith is such a natural part of our life, so it’s going to be infused in all of our storytelling.

But I’d get bummed out if somebody missed out on our film because they don’t watch faith-based movies. I think if something’s trying to preach at you or convert you to a certain way of thinking, that’s one thing. But a lot of films could be considered faith-adjacent because of the beauty of the characters’ lives, the richness in how they exist, and how they spend their time, including how they pray. It’s such an inward matter. Humans look at outward appearances, but the Lord sees the heart.

The struggle you’re articulating is indicative of the central tension of being a person of faith in a creative industry, where you have to make products that appeal to a wide base of people, but you’re also bringing forth something from your inner life. And you want to be true to that inner life as much as possible because that’s part of what audiences react to. Audiences can sense when something is authentic, versus when they’re being pandered to. So it speaks to the quality of your work that you were able to persevere and get people on board. What lessons have you learned from this experience that you might pass on to other aspiring filmmakers?

ANDERS: Doing this project has been like Film School 101. It’s such a complex, all-encompassing medium to work with, it’s really expensive, and it requires so much from you. I would tell most aspiring filmmakers that it’s not worth it unless you really believe firmly in the story and the timelessness of it.

That’s been one of the biggest, most gratifying parts of this. We had to develop a level of consistency to bring this across the finish line. It was basically an unpaid project for five-plus years that we worked on almost every day. So when we look back on this years later, we might cringe at some of our artistic choices along the way, but the guts of this film is something we will always be proud of. We were able to get a nationwide release, which was bigger than anything we’d initially dreamed about—but we were also able to say something deep, meaningful, and personal and to include spiritual themes. And to have partnerships with a fast food chain and the Green Bay Packers—it’s just been a really fun, exciting stew of complexity.

DAVIN: My advice would be to work within your means and stay small. We’ve talked with a lot of producing friends and people writing stories and scripts, and there are so many projects that are difficult to make. First you want to ask, “What’s a story that I can tell that nobody else can?” But then your next question should probably be, “What’s the least amount I could spend to make this story?”

Because the old Hollywood way is over, and with all the new tools available, you can do a lot with a little.