Faith That Sounds Like Lament

“How long, O Lord? Will you forget me forever?

How long will you hide your face from me?

How long must I bear pain in my soul,

and have sorrow in my heart all day long?”

—Psalm 13:1–2 (NRSVUE)

Some songs are just sad. That’s the point. They don’t try to cheer you up or rush to a solution—they just sit with you, right where you are.

I love songs like that.

Only recently did I realize how much the Psalms of lament sound like the music I turn to when life goes sideways—when things fall apart and I’m left with only questions. Psalm 13 is a perfect example. It begins with a cry: “How long, O Lord?” This isn’t a polite prayer. It’s exhaustion. A voice worn down by injustice and tired of feeling unseen.

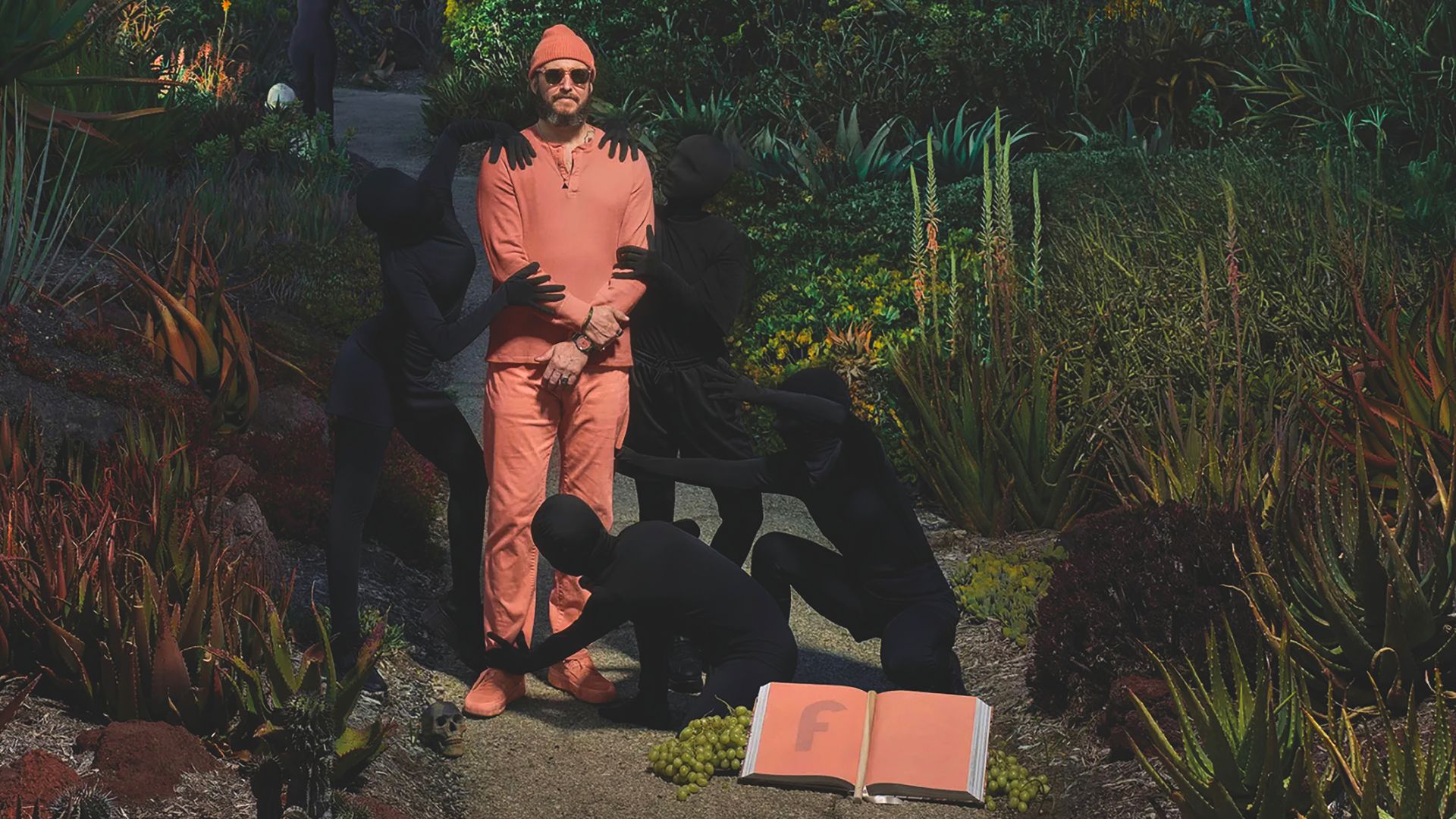

That same brutal honesty is part of why I’ve always been drawn to the music of Bon Iver—the project of singer-songwriter Justin Vernon. In 2006, after a breakup and the dissolution of his band, Vernon holed up in his father’s remote cabin for the winter and recorded For Emma, Forever Ago—a modern-day psalm of lament.

My teenage kids call it “sad dad music,” and they’re not wrong. They hear the ache—and maybe they hear something of me in it too. When I reached middle age, some foundational pieces of my life came apart—relationships, ministry, even my sense of calling—ushering in dark nights I never expected. Bon Iver’s music kept me company—holding the silence, the ache, and the slow work of healing.

This year he released his fifth album, SABLE, fABLE (styled with contrasting caps), in two parts: a three-song EP in the fall, followed by a nine-track collection in the spring. SABLE evokes darkness and mourning, while fABLE suggests a story—maybe even a lesson. Taken together, the album has the shape of a psalm: it begins in lament and turns toward something more alive. Not exactly triumphant, but forward-facing—like someone who’s been in the dark long enough to sense the first light.

Psalm 13 does something similar. It begins in anguish—“How long, O Lord?”—and ends with a decision to trust: “But I trust in your unfailing love; my heart rejoices in your salvation.” Nothing explains the shift. No angel appears, no miracle arrives. Just a choice to keep singing, letting lament and faith share the same song.

As the album transitions from the ache of S P E Y S I D E (“Nothing’s really happened like I thought it would”) to the sheer joy of Everything Is Peaceful Love, two pivotal songs stand out. In AWARDS SEASON, Vernon’s voice is bare, the arrangement spare. He sings, I can handle / Way more than I can handle. The paradox of barely holding on while refusing to let go—strength and exhaustion, intertwined.

Then there’s a brief silence before Short Story breaks in. The sound swells—Vernon’s voice lifted by a wave of brightness—as he sings: Oh, the vibrance. Sun in my eyes… January ain’t the whole world. For those who’ve followed Bon Iver from the beginning, it’s a striking shift. The line reaches back to For Emma, Forever Ago, born out of heartbreak and winter solitude. Vernon once said, “Emma isn’t a person. Emma is a place you get stuck in.” That album became a symbol of sorrow and defined his musical identity for years. But this moment feels like something breaking free. A reminder we don’t have to stay in the dark. Lament is holy—but it’s not all there is. Joy can live beside sorrow. Hope grows in winter. Even in uncertainty, faith keeps singing.

What I’ve come to see is that lament isn’t the opposite of faith. It is faith—stretched thin, worn raw, but still showing up. Still singing. It’s what faith sounds like when you’ve hit the wall, when nothing makes sense, when you’re carrying far more than you ever thought you could. Lament is the sound we make when we’re still reaching for God in the dark. And somehow it becomes the ground where joy begins to grow. Not because the sorrow disappears, but because God’s presence shows up right in the middle of it.

This summer, I’m getting married—joining a new family, a new church, a new chapter I once thought might be out of reach. What surprises me is how joy returned. It didn’t wait for everything to be fixed. It showed up—with grace and laughter—in the middle of the mess. I used to think lament had to end before joy could begin, as if they were separate destinations. But the psalmist doesn’t do that. Vernon doesn’t either. They don’t ignore the sorrow—they let hope live alongside it. Christian hope doesn’t erase the pain, but it tells us sorrow isn’t the whole story. “The night is nearly over; the day is almost here” (Romans 13:12).

If you’re still in the how long part of your story, it’s okay to sing sad songs. It’s okay to pray to a God you aren’t even sure can hear you. Crying out is still an act of faith. Not certainty, but trust—stretched thin, still reaching.

But that doesn’t mean God is absent, unable, or unwilling to bring unexpected good from unexpected pain. There’s a reason the psalmist keeps singing: How long, O Lord? He hasn’t given up on being heard. Neither should we.