Covenant Foundations

The Evangelical Covenant Church was established in Chicago on February 20, 1885, by Swedish immigrants. These immigrants had begun arriving in America in the mid-1860s, near the end of the Civil War. Known as Mission Friends, they were nurtured by the religious and folk renewal movements in Sweden.

In 1868, Mission Friends began organizing congregations in Iowa at Swede Bend, and in Illinois at Galesburg, Princeton, and Chicago. Mission Friend activity began in Minnesota as early as 1866, and by 1870 congregations had formed there in Swift and Kandiyohi counties. Soon congregations followed in the Twin Cities and surrounding counties, in the eastern Dakotas, and in western Wisconsin. Along with congregations in Minnesota’s Red River Valley, these areas formed the Northwestern Missionary Association (today the Covenant’s Northwest Conference) in October 1884.

During the nineteenth century, Mission Friends formed congregations within regional conferences throughout New England, New York, the Great Lakes states, the Midwest, and on the West Coast.

Who were these Mission Friends, or Covenanters? Why were they led to form new congregations and eventually a denomination?

The movement began in Sweden. It grew first among the evangelical followers of Carl Olof Rosenius (1816-1868) within the Evangelical National Foundation (part of the Church of Sweden), and later among the followers of Paul Peter Waldenström (1838-1917), who gathered in intimate religious meetings or “conventicles.”

These meetings grew into local, regional, and provincial mission societies. Both ordained pastors and licensed lay preachers or “colporteurs” led these societies. The piety and convictions of these leaders were warmly expressed by the spiritual songs they wrote and sang, their passion for mission at home and abroad, and their deep commitment to personal, relational experiences.

As a consequence, the Covenant Church (Svenska Missionsförbundet) was first formed in Sweden in 1878. The American denomination followed in 1885, having experimented with their own Lutheran Mission and Ansgar synods during the 1870s and early ’80s. The Swedish Mission Friends and American Covenanters created a vibrant transatlantic movement. It was enriched by immigration, the particular histories of Sweden and the United States, and the vitality of its leaders and people, who tended to be young.

The Covenant gathers believers with mutual experience of new life in Christ and although without a formal confession, the Covenant rests its identity on the following affirmations:

- the Bible as the only authority in matters of faith, doctrine, and life;

- the necessity of the new birth;

- the church as a fellowship of believers;

- the commitment to the whole mission of the church;

- a conscious dependence on the Holy Spirit; and

- the reality of freedom in Christ.

The text that a young pastor, F. M. Johnson, chose for his sermon at the 1885 organizational meeting in Chicago simply expresses the central commitment of the Covenant Church: “I am a companion of all who fear thee and of those who keep thy precepts.”

Pietist Roots

All Swedish American churches share the historical movement of Pietism because of its formative role in the popular 18th- and 19th-century renewal movements in Sweden. The Evangelical Covenant Church (Covenant) continues to be very conscious of core Pietist principles as central to its identity.

Swedish Pietism is usually traced to German pastors such as Johan Arndt (1555-1621), Philip Jakob Spener (1635-1705), and August Hermann Francke (1663-1727). Arndt’s devotional book True Christianity (1605-1609) was in many Swedish homes; Spener’s Pia Desideria (1675) offered a practical program of reform for the ills of the church; and Francke’s work at the Pietist university at Halle offered an example of engaged faith that included children’s homes, a library, hospital, apothecary, missionary training institute, publishing house, and education for children as well as those preparing for various forms of ministry.

By the early 1720s, Pietism was an international movement. It spread to Sweden through pastors and lay leaders, and especially by prisoners of war returning home after the European religious wars of the early 1700s.

Pietism was a reaction to a perceived “dead orthodoxy” in the churches: mere intellectual assent to dogma and excessive attention to divisive theological controversy. It also sought to renew churches devastated by the Thirty Years War (1618–1648) by meeting people’s needs with a balance of head and heart, and through lives of faith active in love.

Spener’s reform program proposed:

- more intense study of Scripture,

- the spiritual priesthood of the laity,

- the experience of conversion—the new birth,

- charity in controversy,

- reform of theological education, and

- encouragement of a godly ministry through preaching that encourages the reality and growth of believing faith.

He accomplished this in his own parish in Frankfurt through conventicles (collegia pietatis), small groups who met for fellowship and edification (the church within the church). Orthodoxy seemed to ask, “Are you sound?”; the Pietist inquired, “Are you saved?”

A form of Pietism emphasizing personal experience even more was the Moravians’. These followers of Count Nicholas Ludwig von Zinzendorf led the first Protestant missionary movement in the early 18th century. The impact of the Moravians and other forms of “classical” Pietism led to the Swedish Edict against Conventicles (1726), which outlawed meeting in small groups outside the parish church and without the supervision of the pastor. This edict was not repealed until 1858, when religious toleration finally came to Sweden.

As the Swedish church and state strengthened supervision during the 18th century, Pietism grew in local communities until a great religious awakening began to unfold in the 1830s. The awakening was fed by outside streams of 19th-century evangelical renewal, especially from England and North America.

The Covenant Church is indebted to Pietist emphases on:

- conversion and the reality of the new life in Christ,

- discipleship and the devotional life,

- shared calling of laity and clergy,

- evangelism and mission, and

- institutional ministries of compassion, mercy, and justice.

The Moravian influence is traceable in Covenanters’

- Christ-centered spirituality,

- concept of God as welcoming friend and Christ as a redeeming brother and companion on the pilgrim journey, and

- sense of that journey as characterized by great joy and gratitude.

All this is especially evident in the spiritual songs of, for example, Lina Sandell, Carl Olof Rosenius, and Nils Frykman.

Revival

“Are you living in Jesus?” This question typifies Covenant Church members’ concern for family and neighbors and for their relationship to God.

The revival among Covenant Swedes at home and in the new land was characterized by the three “C’s”: conversion was the message, the colporteur was the messenger, and the conventicle was the method. While American revivalist methods emphasized mass evangelism, the sawdust trail, and “hell, fire, and brimstone” judgment, Pietist renewal emphasized a loving, patient God who cares for his children by seeking and finding them each personally.

A patient God prevails in Covenant stories of finding new life in Christ, in the sermons of pioneer preachers, and in Covenant Church music, where the invitation to believing faith often takes the form of questions that in time must be answered for oneself. One of many examples is Andrew L. Skoog’s “O that Pearl of Great Price! Have You Found It?”

This gospel invitation centers on extending hospitality, nurturing relationships, and sharing conversation. In Princeton, Illinois, for example, the Covenant congregation began in 1868 among Mission Friend immigrants who launched a revival by asking, “Are you living in Jesus?” over lunch or during coffee breaks while helping each other in the fields.

Erik August Skogsbergh emigrated in 1876 from Sweden to Chicago where he became friends with the evangelist Dwight L. Moody. Moody’s evangelistic influence blossomed during the mid-1870s and profoundly affected believers in Scandinavia and immigrants to America.

Soon Skogsbergh was holding revival campaigns across America that earned him designation “the Swedish Moody.” He adopted Moody’s methods of mass meetings, worship centered on the evangelistic pulpit, and pragmatic experimenting in effecting conversions.

A man of immense energy with a big heart and warm sense of humor, Skogsbergh was fit for this moment of revival and church building. Confident that “the fields were white unto harvest,” he gathered energetically among his fellow immigrants in Minneapolis. Nils Frykman in Kandiyohi County and other colleagues of Skogsbergh, however, often reminded him that “not every day was Pentecost” and that the Spirit blows where it wills.

For Skogsbergh, his colleagues, and their Mission Friend parishioners, conversion was “the one thing needful” and holistic evangelism the core of the Covenant mission. As one Covenanter put it, “We befriend others, and all that God has made, in the name of the one who first befriended us.”

Scripture: Freedom and Authority

“Where is it written?” prompted the Covenant’s decision to claim the Bible as the sole authority in matters of faith, doctrine, and life. In 1870 a group of ministers in Sweden were discussing over coffee “atonement,” the confessional understanding that Christ, through suffering and death on the cross, took on the punishment that humankind deserved and appeased God’s wrath. One pastor asked, “Where is it written?”

Paul Peter Waldenström took the question seriously. Ordained in the Church of Sweden, he held a PhD in classical languages and literature from Sweden’s oldest university, Uppsala. In 1872 after intensive study of Scripture, Waldenström injected into the debate raging both in Sweden and North America an earthshaking sermon published in the Pietisten. He proclaimed that God’s love, not wrath, was the motivating work of atonement. Otherwise, it was God who needed to be reconciled, not humankind, and God was the object, not the subject of Christ’s death and resurrection.

For most Mission Friends, Waldenström’s formulation squared with their own experience of conversion. Swedish Archbishop Nathan Söderblom would later say that Waldenström had restored to the Swedish people an evangelical view of God, a face of love and not angry judgment. The formulation also led those organizing the Covenant Church not to adopt formally the Lutheran Augsburg Confession or write a creed of their own. Everyone was free to read and think for themselves in accordance with the Bible. Wisdom came from the believing community in conversation with one another and dependent on the Spirit’s leading.

This theological freedom in the context of the Bible’s authority is highly prized by Covenanters. David Nyvall, founding president of the Covenant’s North Park University in Chicago, said that freedom was the last of the spiritual gifts to mature.

This question so simply stated, “Where is it written?” does not give Covenanters license to search Scripture for simple proofs. Its intent is to ask, “What do the Scriptures say?” and invite study and conversation of biblical texts to discern God’s truth amid each pilgrim’s journey. At times this may lead to disagreement or ambiguity, but cohesion of the church relies on the shared life in Christ, not on everyone agreeing.

Covenant people have always lived amid creative tension. One old immigrant woman wisely said, “It is not too difficult to love someone whose heart is right, even if their head leaves something to be desired!” The Covenant wishes to honor an old maxim, widely quoted by Pietists: “In essentials, unity. In nonessentials, freedom. In all things, love.” Covenanters continue to find their personal and communal anchor by asking the question, “Where is it written?”

Pilgrim Journey

“How goes your walk?” Early Covenanters understood the Christian life to be a lifelong pilgrim journey. The journey begins with the grace and promise of baptism and must travel through conversion, however that transformation to new life is experienced. Covenant songs richly express “pilgrimage,” a theme that swelling migration, with its separation from home and loved ones, gave even deeper significance, whether one left Sweden or stayed. With this multilayered physical and spiritual geography of home, early Covenanters often “sang a verse and cried a verse.”

The pilgrim journey is a life of growth, discipleship, and maturation. It is natural, then, to ask each other how it is going: “How goes your walk?” The challenges and blessings, joys and sorrows, are to be freely shared communally in informal and more structured ways.

Covenant people, then and now, prize attentiveness to the spiritual growth of their children. Shaping and directing young people’s journeys is expressed through nurture at home, Sunday schools, youth organizations, camps and conferences, and intergenerational care and concern. Many early congregations had “Swede Schools” so that children would not lose the language of their cultural and spiritual inheritance. Although Swedish cultural expectations could be burdensome to a rapidly Americanizing second generation, “How goes your walk?” and its implied encouragement overrode intergenerational differences.

The need for education is common to all immigrants new to America’s dynamism and heterogeneity. Among Covenanters, a new generation of pastors as well as immigrant greenhorns sought the learning necessary to interpret and manage life in the US. Early on, the Covenant saw a need for schools with a clear mission and a readiness to deepen the experience of the Christian life.

Following the short-lived Ansgar College in Illinois (1873-1884) and the offer of the Congregationalists to educate Covenant pastors at Chicago Theological Seminary and at Carleton College in Northfield, Minnesota, the Covenant finally established its own school, North Park University. In 1884, Erik August Skogsbergh began what became North Park in his Minneapolis home. After stops in a Riverside Avenue storefront and the basement of Skogsbergh’s new Tabernacle, the Covenant assumed responsibility for the school in 1891. In 1894, it moved to Chicago. North Park University today fulfills its educational mission in one of the most diverse, multiethnic neighborhoods in the United States.

The Covenant’s other school, Minnehaha Academy, was organized in 1905. Built on a former dairy farm at Lake Street and West River Road in Minneapolis, the academy opened its doors in 1913 to students from throughout the “Northwest” in secondary, music, and commercial programs. Following the Great Depression of the 1930s, Minnehaha became a four-year coeducational high school. Today its educational program extends from preschool through grade 12.

In 1989 CHET (Centro Hispano de Estudios Teológicos) was founded to equip Spanish-speaking leaders for the church and the community. In 2010 the school moved to its own facility in Compton, California. From its inception with 25 students, CHET has taught more than 10,000 students.

Songs, schools, and an abiding question, “How goes your walk?” all are elements of Covenanters’ encouragement, especially to the newcomer and the young, on the pilgrimage each is traveling.

Covenant Home and World Mission

“Whom shall I send and who will go for us?” As people who came from the Swedish Mission Friend movement of renewal, Covenanters are friends of mission. Mission is at the core of the denomination’s identity and is deeply rooted within Pietism. August Hermann Francke, that founding figure of Pietism, said that Christians live for “God’s glory and neighbor’s good.”

Covenant people have faithfully responded through the generations to “Whom shall I send and who will go for us?” with the words of Isaiah, “Here am I, send me!”

“Home mission” has taken many forms:

- Covenant missions to immigrants developed at Castle Garden and later Ellis Island in New York, and to sailors along the eastern and western seaboards.

- What began as “homes for the aged” became retirement communities and are now Covenant Living Communities and Services, offering a range of services from independent living to extended care.

- The “Home of Mercy,” established in Chicago in 1886, expanded to become a major medical center, Swedish Covenant Hospital. In 2019, it became part of NorthShore University HealthSystem.

- Benevolent work with children has occurred at homes in Cromwell, Connecticut, and Princeton, Illinois.

Regional conferences continue to plant new churches and have pioneered a camping movement that is year-round and for all ages. Local congregations engage in a host of ministries to meet needs in their communities.

From its inception the Covenant has been involved in world mission, beginning in 1889 with the labors of Axel Karlsson in Alaska and in 1890 with the arrival in China of Minnesota farmer Peter Matson. The work expanded to other regions in Africa, Asia, South America, Europe, and Middle East North Africa. Often in cooperation with other churches or local partners, Covenant global service has included ministries of medicine, education, agriculture, technology, and development. Today the Covenant Church in Congo, begun in 1936, is larger than the denomination in the United States and Canada and continues to grow rapidly despite the devastation of an ongoing civil war.

The Covenant Church honors the memory of its missionary martyrs. In 1948, for example, Martha Anderson, Esther Nordlund, and Dr. Alik Berg were murdered by bandits in China on their way to attend a missionary conference. In 1964, Dr. Paul Carlson’s plight gained international diplomatic attention and press coverage as Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) became independent from Belgium and revolutionary forces accused Carlson of being an American spy and jailed him. Though his family and other missionaries were evacuated, Carlson remained behind with his patients and was killed as Belgian forces attempted to free him.

Today the Covenant has partnerships in 54 countries across five regions throughout the globe. Covenanters’ response to a call of commitment, sacrifice, and global service deepens the denomination’s experience of the rich diversity of Christian belief and expression as western churches work alongside non-western, indigenous churches.

Strength Through Diversity

“What does the Lord require of you, but to do justice, love kindness, and walk humbly with your God?” In word and deed, the Covenant Church strives to answer faithfully this injunction from the prophet Micah.

Founded by Swedish immigrants, the Covenant continues to be an immigrant church. Post-World War II urban demographic change and post-1965 immigration patterns have transformed the Covenant from an ethnically and racially circumscribed denomination to one of the most diverse churches in North America. How did this transformation happen?

Oakdale Covenant Church in Chicago, Illinois, was the first Covenant church with a majority African American congregation, and its history provides a lens through which to see the larger history of African American Covenanters.

Oakdale was established in 1902 as a predominantly Swedish congregation. By 1967 its attendance had shrunk below twenty people, due to the white flight that followed the Great Migration of African Americans from the rural South to the urban North after the first and second World Wars. Other Covenant churches in Chicago responded to these changes by closing or moving to the suburbs, but Oakdale decided to stay in the city and continue ministry with a goal of racial integration. From 1969 to 1970, Willie Jemison, an African American pastor, and Craig Anderson, a white pastor, served a racially mixed congregation together.

However, demographic changes continued pressing Oakdale Covenant Church in new directions. By 1975, the church was flourishing as a majority African American congregation under the leadership of Willie Jemison. Oakdale continued to grow and expanded its ministry to include the Oakdale Christian Academy and Childcare Center, which address the educational needs of the community. Jemison (1929–2011) continued to serve the congregation and mentored many other African American pastors in the Covenant.

The African American presence in the Covenant continued to grow. Jerome Nelson became the first African American conference superintendent in 2005 and served the Central Conference until 2017. Some African American churches in the Covenant parallel Oakdale’s history of demographic forces redefining congregations, whereas others, such as the multiracial Citadel of Faith Church in Detroit, Michigan, were Covenant church plants. Still others, such as Walk of Faith Covenant Church in Mound Bayou, Mississippi, are deeply rooted in historic African American communities. These varied histories are part of the greater story of God’s work within the Covenant that continues to move the church closer to the founding ideal of the denomination: that the church be “as big as the New Testament” and a true reflection of the kingdom.

The first Latino Covenant congregation was started in La Villa, Texas, in the early 1950s. After World War II, First Covenant Church in downtown Los Angeles experienced white flight to the suburbs and a new wave of Latino immigrants from Mexico, Cuba, Central, and South America. A vigorous Latino congregation developed there in the 1960s under the leadership of Eldon and Opal Johnson, Covenant global personnel who returned from Bolivia. Soon it accommodated more than 300 people from 15 different nationalities.

When the neighborhood demographics shifted to become more commercial the hyphenated membership of First Covenant voted to sell the building. Part of those proceeds prepared the soil to begin Centro Hispano de Estudios Teológicos (CHET), the Covenant Latino training center, in 1989. Latino pastor and seminary professor Jorge Taylor became its first president, leading the new school in its mission to equip Spanish language pastors, evangelists, counselors, global personnel, and lay leaders. Under the leadership of Jorge Maldonado, CHET’s second president who served in that role for 13 years, CHET grew through satellite and distance/online courses. CHET alumni serve the Covenant in leadership roles throughout North America and around the world.

Douglas Park Covenant Church in Chicago experienced a transition similar to First Covenant Church in Los Angeles. The third oldest Covenant church in Chicago, Douglas Park served a largely European American population through World War II. The growth of a Latino community in the neighborhood in the late ’50s and ’60s led to increased outreach under the leadership first of Carl King and Paul Stone, then of Richard Carlson and Herbert Hedstrom, supported by the Department of Home Mission. Daniel Alvarado was called to Douglas Park in 1972 as the first Spanish-speaking pastor, and Iglesia del Pacto Evangélico de Douglas Park was formed. It worshiped parallel to the primarily white Douglas Park Church until the latter closed in 1999.

During the heat of the civil rights movement, the first Korean-speaking Covenant churches were formed in San Francisco and Marina, California, under the leadership of Ed Larson, superintendent of the Pacific Southwest Conference, and pastor Elmer Pearson. The number of Korean-speaking Covenant churches continued to grow through the eighties.

Several Asian American churches were planted in the 1990s to combat the “silent exodus” of second-generation Asian Americans, not at home either in the immigrant churches of their youth or non-Asian churches. Among these was Parkwood Community Church, pastored by Peter Cha in the western suburbs of Chicago. An intentionally pan-Asian church, Parkwood became the Covenant’s first second-generation Asian American church through adoption at the 1997 Annual Meeting. Under the leadership of Peter Wong and Jim Gaderlund, Grace Community Covenant Church of Los Altos, California, became the first Asian American Covenant church plant in 1998.

Through friendships and ministry networks of Asian American Covenant pastors, more second-generation churches joined the Covenant. Today vibrant and unique churches are led by Asian American pastors or are predominantly Asian American in their makeup. This is in addition to the immigrant ministries of Korean, Chinese, and Southeast Asian congregations, which vary in size from small to very large. They are monocultural, multicultural, and multiethnic.

Active ministerial associations provide fellowship, encouragement, and training for African American, Latino, Asian American, and Indigenous clergy. In 2004 the Executive Board of the Covenant produced a “five-fold test” to assess the authenticity of multiethnic ministry and diversity in the Covenant, including a commitment to shared power, increased ethnic participation in leadership, and a collective narrative that embraces the diverse stories of those comprising the Covenant. In 2018, the test was expanded to include a sixth “p,” practicing solidarity.

*Text compiled from contributions from Jorge Maldonado, Greg Yee, and Kurt Peterson.

Forward in Mission

Begun in 1885 by Swedish immigrants, the Evangelical Covenant Church has also become one of America’s most diverse churches, with more than 35% of its congregations classified as ethnic (non-white) or multiethnic. The Covenant experiences the strength that comes from diversity.

The Evangelical Covenant Church is committed to the following:

- Proclaiming the generous grace of the gospel to all

- Pressing forward in multiethnic ministry and diversity

- Attending to the health of existing and planting new communities of faith

- Extending greater measures of compassion and justice to those in need

- Forming spiritually mature Christians who live their faith in and through their neighbors

- Calling and equipping women and men at all levels of church leadership

- Exercising stewardship and care for all creation

- Pursuing global opportunities and partnerships

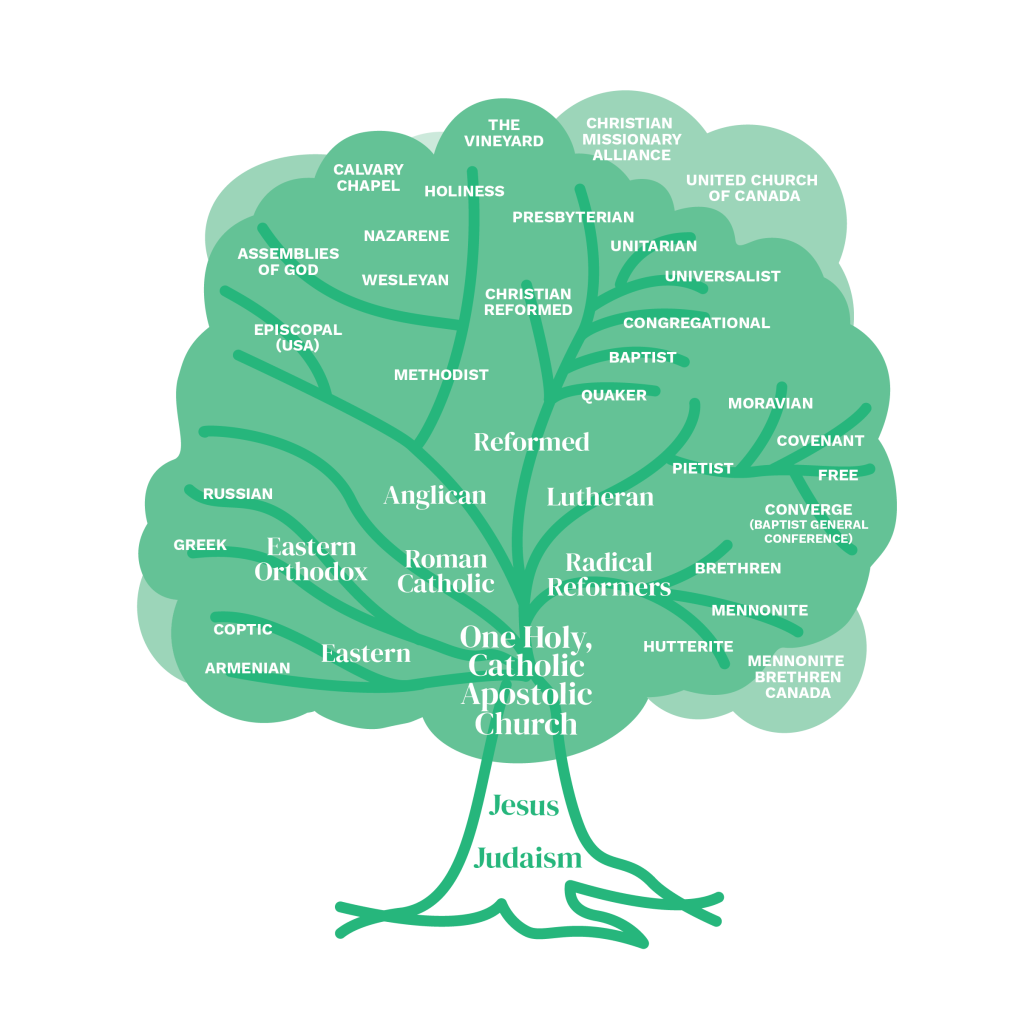

- Participating in the ecumenical life of the one, holy, catholic, and apostolic church throughout the world.