In our culture we aspire to strength and independence, but how do we match that to the teachings of Jesus?

It’s nice to be back at school. Before I begin my remarks, however, I’d like to beg your indulgence. I’ve been in various stages of illness for about a year and a half now, and my own weakness often puts tears a bit closer to the surface than they usually have been for me. I’ve always been the crier in our family. I cry more than my wife, and a lot more than my son. But I’ve been a bit moister than usual of late. So if I get a bit verklempt at some point in the next twenty minutes, bear with me. OK?

I suspect I was asked to speak today because I’m just now returning to school after a long absence. Over many months before last January I had developed a pressure ulcer on, well, let’s just say the place where I sit. It slowly devolved over those months, to the point that my physician finally convinced me to have the wound corrected with surgery, surgery that required a very long hospital stay for recovery. The surgery was performed last January 19. I was released from the hospital to return home on May 20 – not that I’m counting, but that’s four months and a day.

To tell you the truth, the last year and a half has been a difficult passage for me and my family. We honestly wondered if I would even survive. Turns out that I did. But coming so close when you’re about fifty, well, it has an impact. It makes you think. You might be able to imagine that this experience has encouraged me to think deeply about what it means to be ill, what it means to be weak. So I’d like to talk with you about weakness for the next few minutes. It’s a topic with which I’ve become increasingly familiar over the last thirty-two years I’ve spent in a wheelchair, and especially in the last little while.

To tell you the truth, the last year and a half has been a difficult passage for me and my family. We honestly wondered if I would even survive. Turns out that I did. But coming so close when you’re about fifty, well, it has an impact. It makes you think. You might be able to imagine that this experience has encouraged me to think deeply about what it means to be ill, what it means to be weak. So I’d like to talk with you about weakness for the next few minutes. It’s a topic with which I’ve become increasingly familiar over the last thirty-two years I’ve spent in a wheelchair, and especially in the last little while.

Here’s what I think: I think weakness is a Christian virtue, something to which we ought to aspire as followers of Jesus. And I suspect that, if your ears are anything like mine, this sounds a bit odd.

After all, in the world we live in, strength is the greatest virtue, the thing to which we are taught to aspire. We generally present ourselves in the best possible light, which is to say we try really hard to show ourselves to be strong, independent, in control of our own lives and those of others. “Don’t let them see you sweat,” we are told. Even paper towels are presented as strong. You’ve seen those comparisons when the strong paper holds together during a cleanup, but the weak paper comes apart. There’s even one brand of paper towel that features a heavily-muscled guy in a flannel shirt on the front of the package. In a world where even paper towels have to be strong, it’s hard to laud weakness. We all know that strength is good, weakness is not.

I don’t want you to hear me underestimating or sugarcoating or romanticizing weakness, or imagining that it doesn’t hurt sometimes. Even all the time. There are all kinds of things that are symptoms of our weakness: illness, failure, poverty, the death of someone important, loneliness, violence, that kind of personal entropy where it can feel as if parts of us are just flying off us.

And let’s be honest, there are problems with weakness. Weakness can be uncomfortable. Weakness can be dangerous. Vulnerability can threaten you. You can get hurt. You can even die. Weakness can also be humiliating. I honestly don’t remember how many times people would come into my hospital room during the winter and the spring – often these would be people I had never seen before – and say, their eyes flitting between me and a clipboard, “Mr., uhh, Peterson? When was your last bowel movement?” I don’t want to talk about my bowel movements with strangers. Do you?

The surgery I had last January was to repair a big, deep, infected sore on my—OK, I’ll say it—left buttock. When you’ve had that sort of surgery, doctors and nurses want to look at it. And they bring people in to look at it with them. There were times for me when I was turned onto my side so that eight to ten people could stand behind me, inspecting my backside and discussing it together. It sometimes seemed as if I was little more than my wound. I didn’t particularly like that.

No one – certainly no one in his right mind – would choose weakness over strength. And yet, what if that’s a problem? What if it’s a problem that most of us would choose strength over weakness?

So I’ve been thinking. I know that we here at this university are not “the church.” We are, however, a group of mostly Christians who want to encourage one another to aspire to a thoughtful and just faithfulness to God through Jesus. So what if we as a community were to commit ourselves to choosing weakness over strength this year? Instead of pretending to be strong, instead of covering over our zones of weakness, instead of aspiring to control, what if we embraced weakness, chose to be vulnerable, admitted and owned our own and others’ limitations?

I know what you’re thinking. Who is this guy to set an agenda for us for this year? Fair enough. If “setting an agenda” sets your teeth on edge – it does mine – then just imagine that I’m simply a guy making a suggestion. What would it look like if we were to – together – choose weakness?

First, if we were to choose weakness, if we were to embrace vulnerability, we might turn out to be a bit more like Jesus. Christians, of course, have often not been happy with this, and are certainly not too pleased with it in our day. We generally don’t like a weak Jesus, any more than we like being weak ourselves. Instead, we are drawn to a strong Jesus.

Popular culture provides too many examples of this. Have you seen those pictures of a muscly Jesus? These Jesuses, in addition to being ripped, are shown well tanned and brandishing high-powered weapons, ammo slung over their shoulders, or standing in a corner of a boxing ring, boxing gloves on hands, sweating, but enjoying victory. (I’m not kidding.) My brother once saw a t-shirt for sale at a conference for evangelical men. The shirt had a picture of a hand with a lot of blood on it and a spike through the middle, and the phrase “No Pain, No Gain!” I once saw a spoof trailer for a movie about the second coming, featuring weapons fire and rockets red glare, with a voice-over saying, “Jesus is coming again. And this time he means business!”

I, of course, am not the first to notice our collective dislike of weakness and suffering. Theologian Miroslav Volf, in his recent book, A Public Faith, observes, “Sometimes, by some strange alchemy, ‘Take up your cross and follow me’ morphs into “I’ll bring out the champion in you.”

Let me be blunt. If you think that being a Christian is largely about winning, dominion, wealth, influence, political power, and even empire, you’re not following the gospel of Jesus Christ. Because the God we see in Jesus Christ lived out his life in weakness. Jesus was probably pretty poor by our standards. He was not a man possessed of political power or good connections – he seems to have made enemies of most of the powerful people he met. And these enemies succeeded in inflicting upon him that ultimate sign of weakness—the cross. That cross that we’re supposed to take up and then follow him—it wasn’t a metaphor for him. He was publicly and humiliatingly executed on a cross: “He humbled himself…to the point of death – even death on a cross” (Philippians 2:8). So if we were to choose weakness, we might just be a bit more like Jesus.

Second, if we were to choose weakness, if we were to embrace vulnerability, we might be able to receive more gracefully. When you’re weak, it can feel as if you have no choices – as if all doors are closed, all windows are shut, all avenues of escape have been blocked. You have no choice in anything. Instead, things just happen to you.

This, by the way, is a lie. While the range of your choices may be limited when you are weak, this does not mean that you have no choices at all. It’s just that your choices might be difficult to see, and may, indeed, seem too small or too inconsequential to be of value.

During my stay in the hospital last winter, I was quite ill, at least at the beginning. I had one real job given to me by my physicians: lie in the bed until my wound healed. So I was sick and in bed and largely alone for several months. They were pretty bleak times for me, to tell you the truth. My choices were pretty limited. But they weren’t nonexistent.

Sometimes in your life you do things about which you’re really proud – this was one of those moments for me. Aware that I had few options available to me, I decided to try to receive the care given to me by professionals and friends gracefully. I decided to be thankful for every person who came into my hospital room; to be kind to every person who came to visit me or to work on me.

Deciding to do something and actually doing it are different things. To be honest, I failed at kindness more than a few times. But I often succeeded. Honest to God, I hoped that by exercising kindness, I could be a Christian in very difficult circumstances. I could try to be faithful in a context in which I could do little else. I had something that I could do.

Let me give you a single example of receiving gracefully: being washed in bed. Being cleaned by others can easily be humiliating. At times I felt I was a Buick being washed in somebody’s driveway. Still, there is something profoundly moving about being washed as a patient in your bed. You’re ill. You’re recovering slowly. You need to be cleaned. And people, in my experience almost always women, come into your room and they wash you – carefully, lovingly, sometimes even joyously. I remember two women in particular. They were both immigrants from Haiti – Margaret and Rose. Some days these two would come in at the very end of their shifts in the late afternoon and clean me up together. We’d talk and joke and laugh. There was almost something holy about it.

But you need to be able to receive such a gift, almost to revel in your weakness and allow others to give you the help you so desperately need. Receiving gracefully turns out to require a choice; it also requires practice. But my goodness, it can really bring light into your darkness.

Third, if we were to choose weakness, if we were to embrace vulnerability, we might be able to give more faithfully. You know, as do I, that giving is often deployed as a sign of strength. We give to demonstrate how strong we are, how much money we have, and how much influence we can wield. We give with strings attached – in order to put people and institutions into our debt. We give money so that we can control how that money is spent. Giving is all too often a mark of our accomplishment!

I’m not talking about that kind of giving. Instead, I’m talking about giving out of weakness, giving in a context of mutual vulnerability. I’ve tried to think of an example of giving out of weakness that won’t be hackneyed or trite. And I think I found one: some people who visited me while I was hospitalized.

During my months in the hospital, I was blessed with visits from many people. One of my favorite visits happened on February 25, when I’d been in the hospital for just over a month. I know the date and the names of my visitors because I had a guest book that I required them to sign when they came. On that day, five students came to visit me. One of these students, Josh Braman, goes to the same Covenant church on Cape Cod as do my parents. He brought four friends from his small group at school.

This is what I think was going on with their visit. With respect to me, these five students were in a state of relative weakness. Three of them had never met me. Josh and I had spoken only once or twice; and just one of them had ever taken a class with me. In other words, these students hardly knew me. But they had heard that I was hospitalized, and were concerned. Still, they were a bit scared to come and visit me. After all, no one likes to visit a hospital, especially if a professor is there. But these five knew that part of being a Christian is to visit the sick. And so they visited me. In they came and stood at the foot of my bed as we had a conversation. I’ll never forget that sight of those five standing uncomfortably around my bed. Part of me was almost giggling at how afraid they seemed. But most of me was deeply grateful, even moved, by the fact that they had come to see me, to visit the sick.

You don’t have to be strong to give like this to people. In fact, it works better if you’re weak.

I have two final remarks. First, weakness and vulnerability work best when they’re done in community – when they’re mutual. They work best when you can know that I’m not lying in wait to take advantage of you when you let your guard down; when I know that you’re not planning to pounce when I lose my strength. That’s what I meant when I wondered what it might look like if we were to choose together, as a community, to try to live in mutual vulnerability this year.

My final point relates to the passage from the Gospel of John that I have chosen to go along with these remarks today – the final verses of the canonical gospels. “This is the disciple who bears witness about these things, and the one who has written these things down. We know that his witness is true. There are many other things that Jesus did, which, if they were written down in one place, I suppose the world couldn’t contain the books that would be written” (John 21:24-25). As you can see, these verses note that there really is no counting of everything that Jesus did. His activities are just too numerous to be encased in books – even if they’re all the books in the world.

One of the things I like best about the passage is the window it implicitly leaves open: there are lots more things that Jesus, and those who follow him, have yet to do. The story goes on. And it has gone on. There have been faithful people who have been carrying on the presence of Jesus in the world ever since the ascension of our Lord. And we, who wish to follow Jesus, get to be a part of that story.

I’d love it if we as a community of people who aspire to be faithful to Jesus could practice being a bit more like him this year. And being like him, while it’s not limited to these two things, certainly includes them: receiving more gracefully, and giving more faithfully. I wonder what it would look like for us to live like that this year.

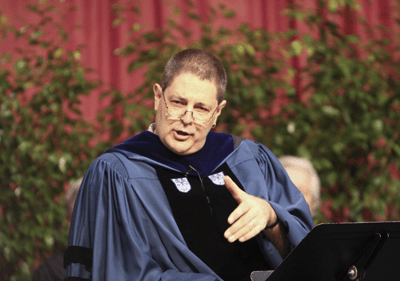

Dwight N. Peterson is professor of New Testament at Eastern University in St. Davids, Pennsylvania. This article is adapted from a convocation address given last fall at Eastern University, where Dwight Peterson has taught for fourteen years. When he was eighteen years old, he contracted transverse myelitis, a disease that affects the spinal cord, and has been in a wheelchair since that time. He and his wife and son live in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania.