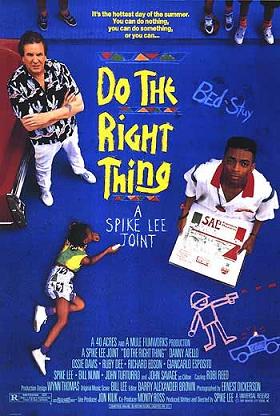

CHICAGO, IL (August 11, 2014) — Editor’s note: 12 Years a Slave and Fruitvale Station each drew multiple awards and critical acclaim earlier this year for their unflinching look at how overt and hidden racial bigotry destroy not only individual lives but corrode society. In 2004, Crash was honored as it explored racial injustice. Before them, though, was Spike Lee’s controversial and groundbreaking Do the Right Thing. This summer marks the 25th anniversary of that film’s release, and it remains as fresh today as it was then.

In order to further ongoing discussions of race and consider ways forward, we are publishing an updated version of an article written by Edward Gilbreath, executive director of Communications for the Evangelical Covenant Church, that first appeared in 2009 on the Urban Faith website.

By Edward Gilbreath

In case you haven’t heard, this summer marks the (25th) anniversary of Spike Lee’s classic and enduringly controversial film Do the Right Thing. The movie first hit theaters on June 30, 1989.

Those of you who have seen the film will recall that it takes place on one of the longest and hottest days of the summer in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyevesant neighborhood. Lee begins the film slowly and deliberately, painting a picture of a predominantly black neighborhood made up of a diversity of people, characters, and races that each bring something unique to the urban landscape. It’s not Norman Rockwell harmony, but it’s a real-life community where disparate parts manage to get along. But, as is usually the case when it comes to race relations in America, tension and unrest are simmering beneath the surface.

Those of you who have seen the film will recall that it takes place on one of the longest and hottest days of the summer in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyevesant neighborhood. Lee begins the film slowly and deliberately, painting a picture of a predominantly black neighborhood made up of a diversity of people, characters, and races that each bring something unique to the urban landscape. It’s not Norman Rockwell harmony, but it’s a real-life community where disparate parts manage to get along. But, as is usually the case when it comes to race relations in America, tension and unrest are simmering beneath the surface.

If you haven’t seen the film yet, please forgive (or avoid) the spoilers that follow the original 1989 trailer below.

Lee plays Mookie, a pizza delivery man for Sal (Danny Aiello), an Italian-American whose restaurant has been on the same corner since the old days (i.e., before the neighborhood became mostly black). The blacks in Bed-Stuy have a sort of love-hate relationship with Sal’s Pizzeria. While it’s nice to have a spot for tasty pizza in the ‘hood, there’s an ambivalence about the fact that one of the community’s primary businesses is owned by a white man. During the film’s climax, Buggin’ Out (Giancarlo Esposito) and Radio Raheem (Bill Nunn) confront Sal to demand he put a black face among his all-white wall of fame. A fight ensues, and when the police show up, Raheem is choked to death by an NYPD officer, which sets off a horrible riot.

This 1989 review by critic Roger Ebert offers a good overview of the movie. Suffice it to say, Spike Lee’s film, like any good piece of art, is open to a variety of interpretations. He doesn’t tell you what to think, though it’s easy for some to come away with the sense that, ultimately, the film is a call for some degree of black nationalism and militancy—or for black folk to at least keep the option available.

An obvious question for us today is, how does Do the Right Thing play in this so-called “age of Obama”? Is it still relevant? I’ll resist calling this era “post-racial,” for I’m sure many of you could quickly tick off a thousand reasons why it’s not. But we’ve clearly moved into a different and better era of racial understanding from what we faced in America 20 years ago, right? (Let the debate begin.) We’ve survived Rodney King, the O.J. trial, Clarence Thomas’s confirmation to the Supreme Court, and the first couple seasons of Tyler Perry’s House of Payne. What’s more, we elected an African American president.

Ironically, it turns out that Do the Right Thing was the film that Barack and Michelle Obama saw on their first date, and it consequently holds a special place in their personal history. Newsweek wonders why this seemingly minor but potentially significant fact didn’t get played up more by the media during the presidential race last year, when Obama’s opponents were looking for any and all evidence of his racial and political militancy. And TheRoot.com thinks it’s odd, though not surprising, that Obama himself rarely mentions that aspect of he and Michelle’s first date. (Though, when one listens to Obama’s ruminations on race in America today, you can hear his desire to acknowledge the multiple points of view that usually exist on the different sides of the color and class line in our nation.)

Also at TheRoot.com, journalist Natalie Hopkinson offers a fascinating reassessment of the film’s message and legacy. While she concedes the film’s cultural importance—and confesses that she reveled in the righteous indignation that the film inspired in blacks who had felt oppressed and wrongly profiled for much too long, in retrospect Hopkinson questions the film’s underlying message of angry black nationalism. She suggests that what will be needed for true racial uplift today is not a spirit of racial separation but one of multiracial cooperation. She writes:

In 1989, Do the Right Thing rightly railed against police brutality and institutional racism that reduced the life chances and quality of life of many black people in urban areas. If combating those conditions, which still exist, is what we mean by fighting the power, I will be the first to put on boxing gloves.

But (25) years on, Buggin Out’s kind of fight feels futile. Symbolically and literally speaking, we are the Power. We need Sal’s Famous Pizzerias in the neighborhood, and we need the Mookies of the world to open their own businesses, too. It’s messy. It’s sometimes tense, often uncomfortable. We won’t always understand each other. But come on back. We need that slice.

Hopkinson’s essay, I believe, rightly calls us to “do a new thing”—that is, to allow forgiveness and hope to trump our lingering racial resentment, bitterness, and fear. (This, admittedly, becomes more difficult each time another Trayvon Martin or Eric Garner or Mike Brown incident disrupts the weekly news cycle.) But I don’t think Hopkinson’s change of heart about Do the Right Thing necessarily diminishes what the film was trying to do those two decades ago.

Ultimately, Spike Lee was challenging his viewers to wrestle with their prejudices and misconceptions about the American condition. To his credit, Lee understood that this would mean different things to different people, and provoke different responses based on each person’s life experience. In that way, Do the Right Thing was—and is—a bold piece of filmmaking and a disturbing, sometimes vulgar, but always thought-provoking tool for an honest discussion of racial reconciliation in America.

Commentary, News

Voices: Doing a ‘New’ Thing—Still

CHICAGO, IL (August 11, 2014) — Editor’s note: 12 Years a Slave and Fruitvale Station each drew multiple awards and critical acclaim earlier this year for their unflinching look at how overt and hidden racial bigotry destroy not only individual lives but corrode society. In 2004, Crash was honored as it explored racial injustice. Before them, though, was Spike Lee’s controversial and groundbreaking Do the Right Thing. This summer marks the 25th anniversary of that film’s release, and it remains as fresh today as it was then.

In order to further ongoing discussions of race and consider ways forward, we are publishing an updated version of an article written by Edward Gilbreath, executive director of Communications for the Evangelical Covenant Church, that first appeared in 2009 on the Urban Faith website.

By Edward Gilbreath

In case you haven’t heard, this summer marks the (25th) anniversary of Spike Lee’s classic and enduringly controversial film Do the Right Thing. The movie first hit theaters on June 30, 1989.

If you haven’t seen the film yet, please forgive (or avoid) the spoilers that follow the original 1989 trailer below.

Lee plays Mookie, a pizza delivery man for Sal (Danny Aiello), an Italian-American whose restaurant has been on the same corner since the old days (i.e., before the neighborhood became mostly black). The blacks in Bed-Stuy have a sort of love-hate relationship with Sal’s Pizzeria. While it’s nice to have a spot for tasty pizza in the ‘hood, there’s an ambivalence about the fact that one of the community’s primary businesses is owned by a white man. During the film’s climax, Buggin’ Out (Giancarlo Esposito) and Radio Raheem (Bill Nunn) confront Sal to demand he put a black face among his all-white wall of fame. A fight ensues, and when the police show up, Raheem is choked to death by an NYPD officer, which sets off a horrible riot.

This 1989 review by critic Roger Ebert offers a good overview of the movie. Suffice it to say, Spike Lee’s film, like any good piece of art, is open to a variety of interpretations. He doesn’t tell you what to think, though it’s easy for some to come away with the sense that, ultimately, the film is a call for some degree of black nationalism and militancy—or for black folk to at least keep the option available.

An obvious question for us today is, how does Do the Right Thing play in this so-called “age of Obama”? Is it still relevant? I’ll resist calling this era “post-racial,” for I’m sure many of you could quickly tick off a thousand reasons why it’s not. But we’ve clearly moved into a different and better era of racial understanding from what we faced in America 20 years ago, right? (Let the debate begin.) We’ve survived Rodney King, the O.J. trial, Clarence Thomas’s confirmation to the Supreme Court, and the first couple seasons of Tyler Perry’s House of Payne. What’s more, we elected an African American president.

Ironically, it turns out that Do the Right Thing was the film that Barack and Michelle Obama saw on their first date, and it consequently holds a special place in their personal history. Newsweek wonders why this seemingly minor but potentially significant fact didn’t get played up more by the media during the presidential race last year, when Obama’s opponents were looking for any and all evidence of his racial and political militancy. And TheRoot.com thinks it’s odd, though not surprising, that Obama himself rarely mentions that aspect of he and Michelle’s first date. (Though, when one listens to Obama’s ruminations on race in America today, you can hear his desire to acknowledge the multiple points of view that usually exist on the different sides of the color and class line in our nation.)

Also at TheRoot.com, journalist Natalie Hopkinson offers a fascinating reassessment of the film’s message and legacy. While she concedes the film’s cultural importance—and confesses that she reveled in the righteous indignation that the film inspired in blacks who had felt oppressed and wrongly profiled for much too long, in retrospect Hopkinson questions the film’s underlying message of angry black nationalism. She suggests that what will be needed for true racial uplift today is not a spirit of racial separation but one of multiracial cooperation. She writes:

In 1989, Do the Right Thing rightly railed against police brutality and institutional racism that reduced the life chances and quality of life of many black people in urban areas. If combating those conditions, which still exist, is what we mean by fighting the power, I will be the first to put on boxing gloves.

But (25) years on, Buggin Out’s kind of fight feels futile. Symbolically and literally speaking, we are the Power. We need Sal’s Famous Pizzerias in the neighborhood, and we need the Mookies of the world to open their own businesses, too. It’s messy. It’s sometimes tense, often uncomfortable. We won’t always understand each other. But come on back. We need that slice.

Hopkinson’s essay, I believe, rightly calls us to “do a new thing”—that is, to allow forgiveness and hope to trump our lingering racial resentment, bitterness, and fear. (This, admittedly, becomes more difficult each time another Trayvon Martin or Eric Garner or Mike Brown incident disrupts the weekly news cycle.) But I don’t think Hopkinson’s change of heart about Do the Right Thing necessarily diminishes what the film was trying to do those two decades ago.

Ultimately, Spike Lee was challenging his viewers to wrestle with their prejudices and misconceptions about the American condition. To his credit, Lee understood that this would mean different things to different people, and provoke different responses based on each person’s life experience. In that way, Do the Right Thing was—and is—a bold piece of filmmaking and a disturbing, sometimes vulgar, but always thought-provoking tool for an honest discussion of racial reconciliation in America.

Covenant Companion

Share this post

Explore More Stories & News

Basement Therapy

Jacob and the Love That Carries On

A Light That Lingers

Jotham and the Joy of Steady Faith

Formation at a Snail’s Pace

Ruth and the Courage to Remain

Journey to Wind River

Abraham and the Courage to Begin Again