Lessons learned in the interlude

“The waiting is the hardest part.” – Tom Petty

Over the last decade, I have had many great experiences in various ministry settings as I finished college, attended seminary, and took my first full-time call in a church. When transitions occurred, they happened some- what smoothly, with little delay. Sometimes I heard friends talk about being in limbo, or I read articles and blogs that explained the ambiguous ache of awaiting a call, but my understanding was abstract and secondhand at best – until it wasn’t.

The past few months I have gained some firsthand experience with the waiting game. Undecided about next steps, unclear as to my options, and unsure of what that meant—about the future, about ministry, about me – I felt like I was living the photographic negative of ministry. The colors were reversed, and the bright areas that usually offered encouragement and hope were now the shadiest parts of the picture. I found myself in a sort of darkroom, hoping that, as with a photograph, processes were happening to me that would develop me.

Of course it didn’t always feel that way. Some- times it just felt like sitting in the dark. Days passed with no discernable progress toward answers or understanding. I was searching for meaning, something I could point to and say, “Oh, it was all for this.” Life is rarely that straightforward, though, especially life with God.

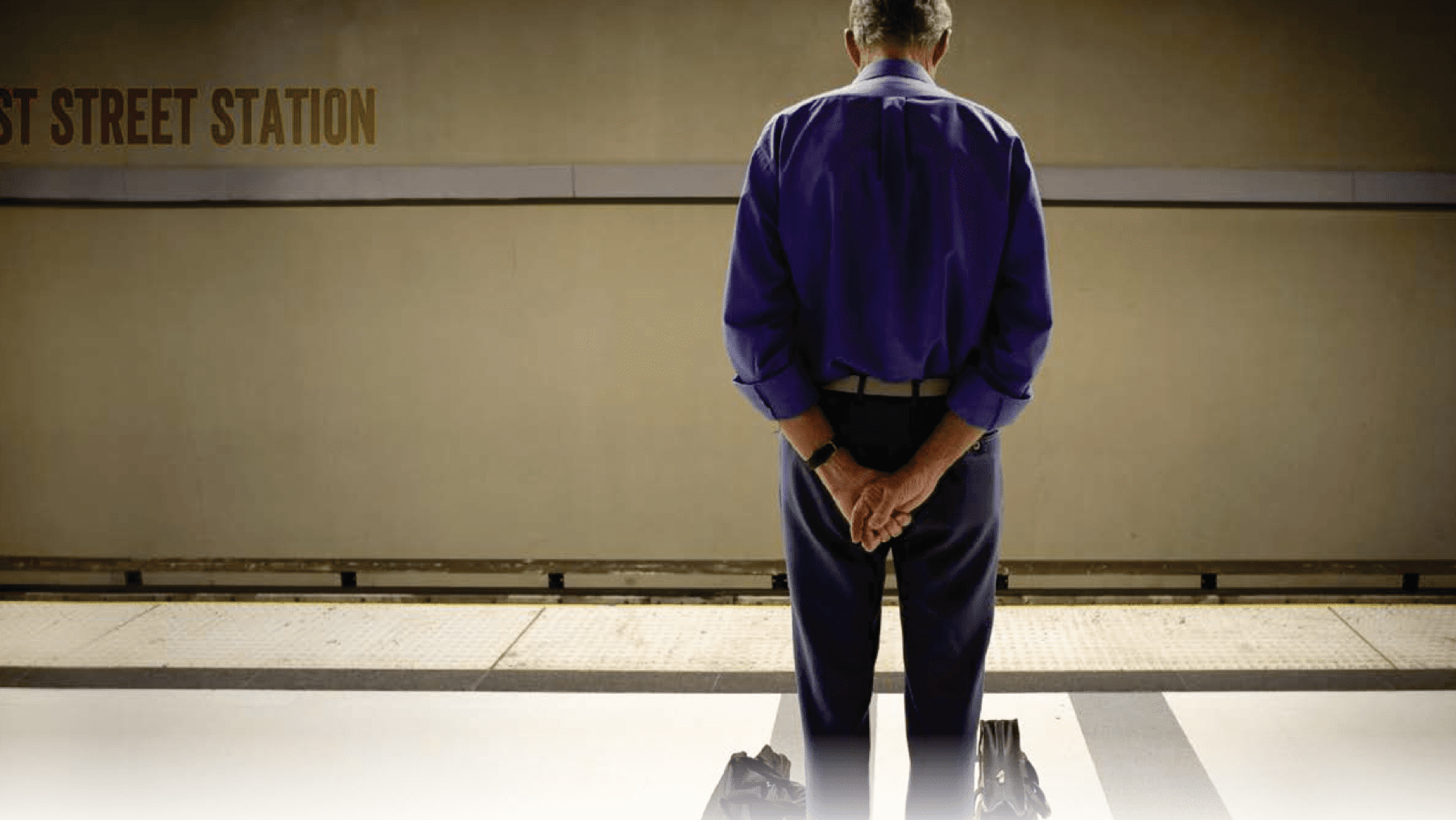

I have friends who have been waiting far longer for answers or meaning or respite from matters much weightier than temporary unemployment. My heart is heavy for them, and though the particulars are different, we share the common burden of feeling fro- zen. We all seem to be standing on the same train plat- form, craning our necks to glimpse a train approaching from the tunnel, a light emerging from the darkness that will carry us toward anything other than more waiting.

Maybe we’ve misjudged the standstill. Maybe wait- ing is more than an experience to be endured. Maybe it teaches us something we can only learn in the interlude.

Maybe waiting itself has meaning.

A lie we often hear – and believe – is that waiting is unproductive. Compound that lie with the false prin- ciple that productivity is the golden standard for our value in life, and no wonder we have negative feelings about waiting. We need to think critically about this assessment. Perhaps we need to consider some other sources before we paint waiting in such a bad light.

In his book Out of Solitude, Henri Nouwen reminds us that “our worth is not the same as our usefulness.” How quickly we forget this, though, and how easy it is to equate the two, especially when we struggle with feel- ing useless. For me, lack of call on the heels of ordination was a bit of a head-trip: one of the most affirming moments of my life followed by a void that left me wondering if somehow my ordination had fallen off. I felt like Peter Pan, crying on the nursery floor as I tried desperately to stick my shadow back on with hope and bar of soap. If Nouwen is right, though, then my worth is based in something other than my employment status. Recently my mom reminded me of one of John Milton’s sonnets, “On His Blindness.” Milton, the seventeenth-century English writer, composed this poem in the midst of, perhaps near the completion of, going completely blind.

When I consider how my light is spent

Ere half my days in this dark world and wide,

And that one talent which is death to hide

Lodg’d with me useless, though my soul more bent

To serve therewith my Maker, and present

My true account, lest he returning chide,

“Doth God exact day-labour, light denied?”

I fondly ask. But Patience, to prevent

That murmur, soon replies: “God doth not need

Either man’s work or his own gifts: who best

Bear his mild yoke, they serve him best. His state

Is kingly; thousands at his bidding speed

And post o’er land and ocean without rest:

They also serve who only stand and wait.”

That last line hit me right between the eyes: “They also serve who only stand and wait.” The personified Patience replies to Milton’s own anxieties about feeling useless, reminding him that God does not need human work or gifts. Human productivity is not the standard by which God measures our service to him.

This idea permeates Scripture, and it is especially evident in the events surrounding the birth of Jesus. So much waiting happens early in the gospels – in fact, the gospels begin at a point when the Jewish people had been waiting for the Messiah for hundreds of years. Hopeful expectance was their way of life. And then God makes known to certain people that the time is almost at hand.

The Hebrew people were waiting for a Messiah. They taught their children and prepared their lives and houses, and they got ready for when the Messiah would show up. It made them live differently.

Every year, we spend four weeks remembering the expectant hope that preceded the birth of Jesus Christ. Zechariah and Elizabeth had been waiting. Joseph waited. Mary waited. God waited nine months in Mary’s womb. Simeon had been waiting his whole life.

When we are waiting, we are living differently. The imminent arrival of a loved one fills a person with excitement and hope. “A thrill of hope, the weary world rejoices, for yonder breaks a new and glorious dawn.”

Jesus is always coming – in unexpected ways and at unexpected times. Maybe the trick is realizing that waiting for Jesus – living in active expectation – is actually the very service that God asks of us.

Maybe Tom Petty is right when he says the waiting is the hardest part. Yet when we wait, we cast down the idols of our own productivity, and we allow God to be God. We enter into the nervousness and fear of feeling ineffectual, but we discover that our worth is not the same as our usefulness. We take our place in the long line of those who have waited, and we live into our identity as God’s people, his servants, waiting on Jesus.

Josh Danielson recently accepted a call to serve as pastor of worship arts at Christ Church in East Greenwich, Rhode Island.