In 2015 North Park Theological Seminary began offering theology courses at Stateville Correctional Center outside Chicago. The letters that follow are from incarcerated students and their professor on their transformative experiences of faith.

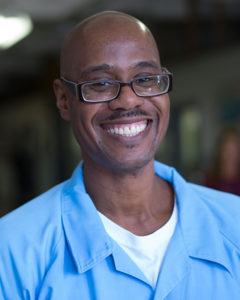

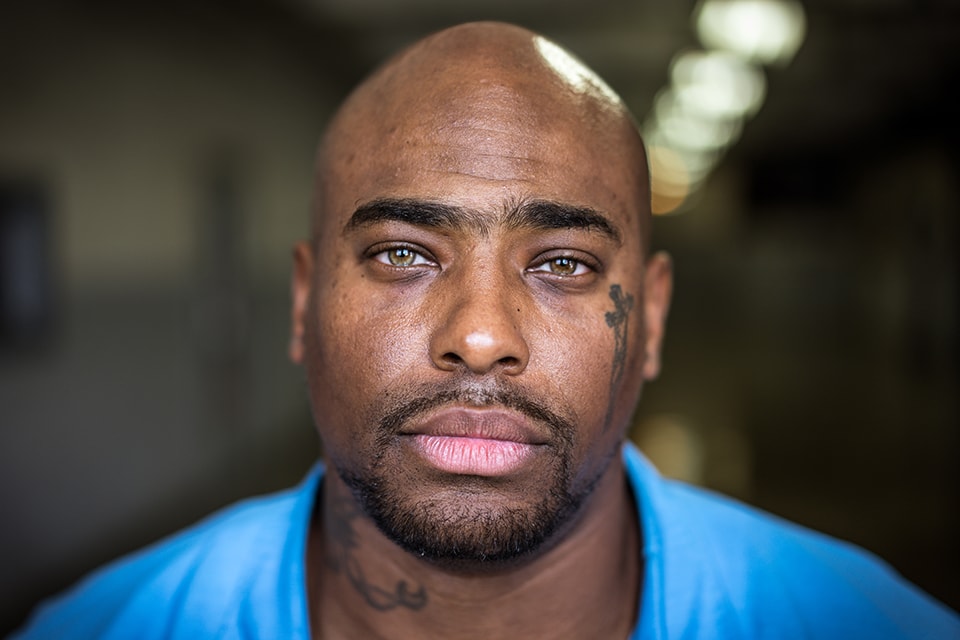

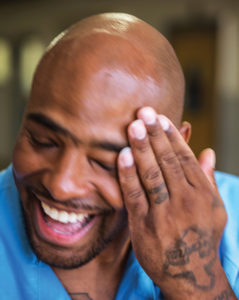

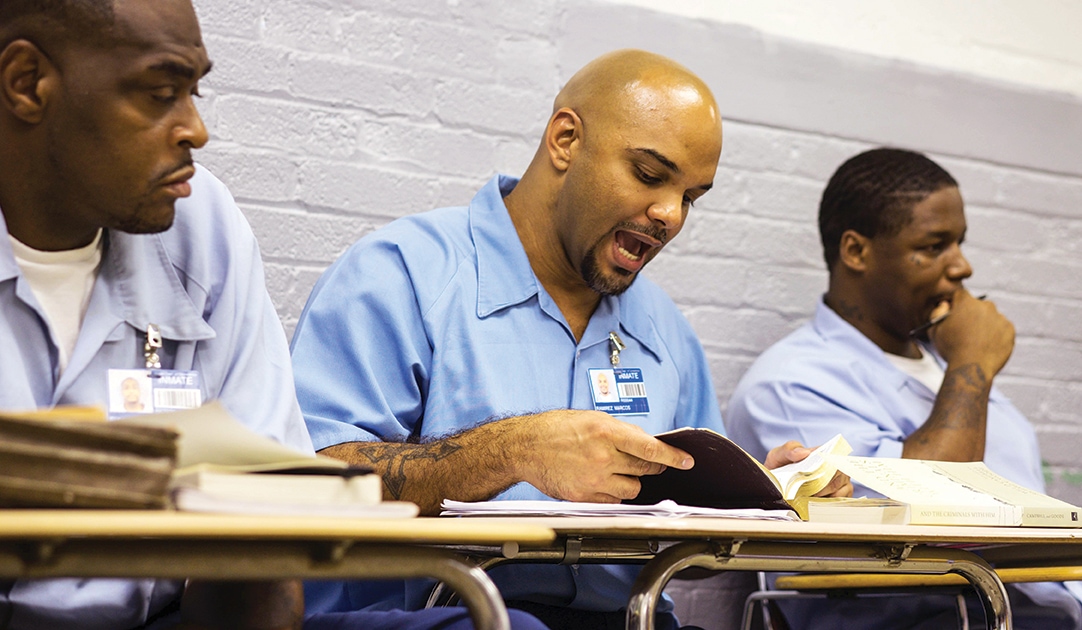

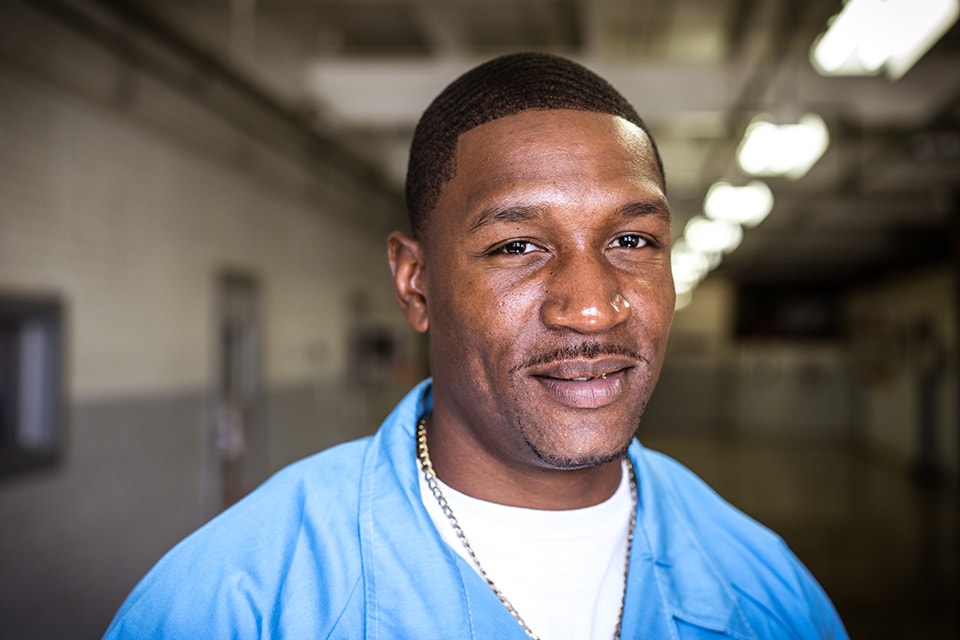

Photos by Karl Clifton-Soderstrom

Blessed Are They

by Michelle Clifton-Soderstrom

The virtues necessary to survive “inside” stand in stark opposition to those depicted in Jesus’s words in the Sermon on the Mount. In his words, the peacemakers, poor in spirit, mournful, meek, merciful, and pure in heart characterize the truly blessed. But in a context where strength and confidence are the tools of survival it’s simply too risky to cultivate those traits.

Prison chaplain Richard Beck writes, “When you read the Beatitudes on the outside of a prison, it all sounds so nice and happy. But read inside a prison and suddenly you see just how crazy you have to be to be a follower of Jesus. You see how the Beatitudes are a matter of life and death.” Meekness is a liability inside prison walls, and even the act of mourning the loss of a brother can be risky.

I learned about the dangerous side of the Beatitudes from a man who was once on death row. In the fall of 2015, North Park Theological Seminary was invited to Stateville Correctional Center by chaplain George Adamson. Stateville is a prison outside of Chicago that houses 3,000 men. For the past year field educator Deborah Penny and I have co-led courses there, which are comprised of both seminary students and Stateville students. We study writings by theologians, chaplains, and advocates—as well as by people who are incarcerated.

Our class had read Beck’s article on the Beatitudes, and one student, David, told us about living on death row—and how dangerous it would be for him to be meek or merciful or a peacemaker. In any prison context—death row or otherwise—being vulnerable is not a safe way to be.

Yet David and many other Stateville residents opened themselves up to the uncertain space—and potential vulnerabilities—of a shared classroom. Learning anything new can be risky. Studying with people of diverse racial backgrounds, educational achievements, and legal statuses—free or incarcerated—is even riskier. It might not get you killed, but it will make you question the meaning of your life.

Things that happen in a traditional classroom happen in the prison. Everyone reads. Everyone writes. Everyone creates, and everyone leads. At the same time, much about our Stateville classroom is far from traditional. Our work and discussions occur inside a 1920s facility with thirty-foot walls and layers upon layers of bars, gates, fences, and concrete. There is the stark reality that some members of the class are able to live their lives freely, while the others are constrained in nearly every movement they make.

When I ended the first class this fall with a benediction, “Go in peace.” Stateville resident Marcos remarked, “Actually, you all get to go. We have to stay.”

It was a moment of marking the divided space between us—a division that goes against the Beatitudes. The Beatitudes are not about being singularly virtuous. Rather, they call us to get into one another’s space and occupy that space in ways that render us poor, meek, mournful, and merciful. The Beatitudes are all about relational solidarity.

As a theological educator in Stateville, I know it is tempting to think we volunteers are the blessing. And it’s true that education is a good thing for those who spend their days behind bars—it significantly reduces re-incarceration rates, saves the state on average $5 for every $1 invested, and increases the opportunity for people to find meaningful work upon release. Within prisons, education contributes to better race relations, generates good communication between residents and correctional staff, and decreases violence.

Yet any claim that we who are free are the ones ministering to or “fixing” those who are incarcerated is misguided. It renders insignificant the transformative work done by the students who are incarcerated. Such misperceptions reinforce the divisions between free and carceral spaces instead of claiming the shared space that is the world we all live in.

Prison is a place that defines people by the worst things they have ever done. Not only is that anti-gospel, but most of us who are free do not live that way. We recognize that Christ’s redemption is open to all who are willing to follow him—and that any who believe open their lives to the dangerous world of defining people by the best of who they are.

Yet defining people by the best of who they are is risky in its own way—far safer to define others by their brokenness and turn away. Locking people up offers the false security that society has dealt with their social problems, and now the rest of us are “safe.” In reality, we have not dealt with our social problems at all. Experts cite primary factors that lead to criminal behavior and incarceration—poverty, unemployment, racism, and lack of access to good education—problems that are still with us, reinforcing the broken system of mass incarceration.

Mass incarceration is not the problem of those in prison alone. Nor are the solutions to imprisonment the solutions of free people alone. There is no magic bullet or quick answers. Nonetheless, our students have courageously worked to overcome these divides.

Most of us do not live defined by the worst thing we’ve ever done. We live in the hope and the power of God to redeem broken lives and divided communities. The Beatitudes in prison are dangerous, but they are dangerous for free people as well. They mean giving up power and privilege. They force us into spaces that make us uncomfortable.

My prayer is that as we hear the voices and see the faces of individual men who are incarcerated at Stateville, we may find the courage to address the social sins we fear to face. Marcos and David and Ryan and Corzell—and so many more—speak into the brokenness that is all of ours. This is one of the blessings the men at Stateville offer us. God is building the kingdom from the inside out.

Thank You, Jesus

by Nathaniel Dixon

When I was a boy in Mississippi, my grandmother and grandfather used to sing an old song around the house. It goes, “I thank you Jesus, I thank you, Jesus, I thank you, Jesus, I thank you, Lord, all you brought. Yes, you brought, me from a mighty, a mighty long way, a mighty long way.”

Sometimes they would sing that song at the strangest times. When the money got low or things got a little tight they would say, “Thank you, Jesus.” When I got in trouble and had to be punished, or it looked like I wasn’t ever going amount to anything, there they went, “I thank you, Jesus.”

To me it looked like they were thanking Jesus because we were in a monetary jam or because I was messing up. But I realize now that I was just looking at the horizontal relationships. I couldn’t see the vertical hookup they had. I didn’t know they were thanking Jesus in advance for all they dared to hope he would one day do in and through their grandson.

That’s what they prayed for. That’s what they hoped for. That’s what they kept waiting for. Now forty years later I can join them in saying, “Thank you, Lord, for how you brought me. Thank you, Lord, for how you taught me, thank you, Lord, for how you kept me; thank you, Lord, ’cause you never left me. Thank you for not letting go of me when I let go of you. Thank you, Lord, for caring more about me than I cared for myself. Thank you, Lord.”

I don’t know what you have to be thankful for today, but whatever it is, I wish you would help me thank him.

True Community

by Michael Sanders

I believe good community is when everyone is working together to help each other out. In a good community no one should be hungry, without shelter, and no one should be denied proper healthcare.

Forgiveness

by David Smith

Author Robert Keck once wrote, “We begin discovering the kingdom of heaven by loving, affirming, and empowering that part of the universe over which we have responsibility—ourselves.”

In 1987, I was twenty-three years old. By that time I had been addicted to drugs and alcohol for more than twelve years. My life was defined by self-destructive behavior and had no purpose or meaning. I was arrested, tried, convicted, and shipped off to death row to be housed with the other dregs of society, until we would be strapped to a gurney and executed in the name of justice.

One might think at some point a person would wake up and decide to do something about their life. But when all you have ever known since as far back as you can remember is abuse, neglect, violence, and a complete absence of love, the condition of the heart becomes so deeply scarred and steeped in anger, resentment, self-hatred, and other destructive emotions that it’s impossible to imagine you have any intrinsic value.

Seven years later I found myself sitting in my solitary cell, high as a kite, music blaring as I tried to drown out the noise inside my head.

Then in an instant, I seemed to sober up and a question repeated itself in my mind: “What is wrong with you?” Suddenly I was moved to tears. It was as if I was viewing myself for the first time from a loving, caring perspective.

That night I decided to find out what was “wrong” with me. The psychiatrist happened to be making rounds in the unit and I stopped him to talk. I told him I had some things going around inside my head that I was trying to understand. Could he help me?

His only response was to ask me if I would take a prescription from him. He didn’t even ask me my name. At that point I had spent almost half of my life medicated with one drug or another, and I decided it was time to take a sober look at my life and start confronting my demons. I chased him away from my cell.

I sent my television and radio to personal property to be stored until further notice. I had less than an eighth-grade education, but over the next five years I spent every waking moment studying. I read every book I could get my hands on related to sociology, psychology, and self-help.

When I turned by eyes inward I found a wasteland of destructive emotions. I was a broken, battered, frightened, isolated child hiding behind the walls of anger, hatred, resentment, and disappointment. I realized I had been living my life wearing a mask.

So, I had to learn to parent myself with the compassion and patience that was missing in my life. I learned to love myself in a way that had been denied me my whole life and to discover my own intrinsic goodness and value.

I also had to learn how to forgive all those who had hurt me, denied me, or failed to love me. I came to understand that we can’t give what we don’t have. Often people who are hurting act out of their own pain and hurt others in turn. What I had to do through the practice of these two principles of love and forgiveness was to make peace and decide to stop passing on the pain.

Through this process I found my calling. I discovered an ability to help others navigate their own winding maze out of emotional bondage into a land of love and freedom. In getting to know many of these men and learning their stories, I became aware that a common thread running through their childhoods is often some kind of abuse and neglect. Most have grown up without an emotionally healthy, responsible parent in their lives. So much of what we experience as children—good and bad—shapes our personalities and affects our lives in countless ways.

I have gained immeasurable joy in this journey and in helping others begin the process of healing the emotional scars that have fueled their addictive, violent, criminal behavior. My goal is to help them understand that our purpose is to discover faith in the Source of love within us, and to express that love in every thought, word and deed. Together we learn to love and value ourselves and use the boundless gifts and opportunities God, in his grace and mercy, gives us to create peace and abundance in our environments and relationships.

Beauty from Dirt

by Manuel Metlock

Over the years I have looked at my pain and struggles as if they were punishments and setbacks in my life. The fact is, the hurt I have endured has molded me.

I have begun to notice that when I speak to people they connect with me because of my pain. I have been able to speak to young people, and they listened and sometimes they changed. They could see the gunshot wounds, the stab wounds, the tattoos—and the hurt in my eyes. They could recognize what was real and connect with the struggle.

My peers can see the change in me, and they respect where I have been and where I am going. Some ask for advice on how to deal with their kids. I try to teach them that their children are not scared to die, they are scared to live as if death has honor and life is barren.

I am learning that my purpose is to preach the word of God through my experiences. Through God’s grace I am able to reach people from very different walks of life because of my pain and what he has taught me because of it.

I don’t believe that preaching is something that you want to do. It should be something you have to do. I didn’t choose to preach, but God is showing me that what I have inside me cannot ever be suppressed.

What is my purpose now? My purpose is not to be a stereotypical preacher, but instead to allow all of my flaws and imperfections to show. “You meant evil against me, but God meant it for good” (Genesis 50:20, NAS). What might have destroyed me, God has used to mold me and make me the opposite reflection of what I once was.

Some people look deep into my eyes and all they can see is the pain. But when God looks at me, all he sees is opportunity. I am God’s example that even from s***, something very beautiful can grow out of the soil.

Ministry of Reconciliation

by Eric Watkins

I was raised by a single African American woman who attended and graduated from two colleges in the 1970s and became a teacher. My mother was a Chicago Public School teacher for more than forty years. To this day, she tells me, “In order to be a good teacher, you have to be a great student first.” Likewise, in order for me to become a better servant of God, I must become a better student of God—and of life.

I graduated from high school when I was fifteen years old, and enrolled in college less than a month later.

I am a wrongfully convicted man, wrongfully sentenced to natural life in prison when I was seventeen years old for a crime I did not commit.

I am a believer in Jesus Christ and I am a minister of his gospel. I am also a student of the law—studying the laws surrounding my conviction, seeking to be free while at the same time helping others learn their rights and how to fight for them. And where I am, many are discouraged and resist help. Many have given up altogether, and even worse, encourage others to do the same.

In prison, I have met people from different walks of life, from diverse educational and cultural backgrounds, who experience various types of brokenness, who need help, who need someone to talk with and share the burdens of their struggles. They seek to find God, to find answers to their problems, be comforted, and alleviate their pain.

My vocation is a ministry of reconciliation. I seek to help mend broken relationships. I have learned that wherever there is brokenness, there is pain also. The Apostle Paul’s encouragement to be gentle unto all (Titus 3:2) is a necessary attitude when performing this surgery of the heart. Yes, like Jesus Christ, the Great Physician, we too, are called to a ministry of reconciliation and healing.

For more than seventeen years, I have studied Christian apologetics, and I have noticed that before I am able to discuss deep theological issues with others I must be able to relate to them. I believe God is using everything I have suffered and experienced in my life for the work of his ministry through Christ Jesus.

Our readings in the inside/outside exchange student programs challenged me to examine my preconceived notions about justice. As a result, I now believe that beyond being a system focused on retribution and making profits off of crime, the foundations of true justice are the essential concepts of love, mercy, and grace. We demonstrate love for all humanity without dehumanizing the victim or the victimizer. We show mercy for the offender and their families, by not seeking to destroy them by imposing the death penalty or natural life sentences. And we extend grace to offenders who are willing and striving to change—especially for adolescent first-time offenders.

I believe that the presence of our inside students and our interactions with the outside students and teachers have broken down many false stereotypes about prisoners. I think the outside members of the classes have gotten to know us as individuals and we became one as a community, and are accepted as their friends.

Last, this course prompted me—as Professor Michelle requires—“to bring my best self, my best decisions, and my best work to class.” I wrote and performed a serious skit, which I had never done before. I had never viewed myself as a writer per se, but I am discovering a talent that can be developed and used for God’s ministry—to draw others to Christ and maybe even help them discover their own vocation as well.

Pinch Me

by Santana McCree

Every time the door locks,

To the man-made Box

Time seems to stop

And I’m wondering if I’m experiencing a paradox.

I pray for the walls to drop,

But instead they start closing in.

So like most men I pretend to be strong,

But deep within,

I know I can’t handle this alone.

How long will this suffering go on?

Will the Father’s light ever shine?

Laughter conceals my crying,

I often wonder if I’m dying,

While the architects of the man-made Box

Concoct new designs to confine.

Please can somebody pinch me?

I think I’m going out of my mind.

I’m seeing long lines of my kind,

And to my surprise some are content

With natural life.

So I’m trying to rationalize such contentment

In an environment filled with so much strife.

Maybe I’m learning to wear my agony?

By mentally making a transition

To the Box reality.

Dissension is so overwhelming in this society.

My only refuge is my dreams,

But for now it seems

That I’m stuck on this page

While lying in this grave

I crave confirmation.

I pray to God to save my soul

Because I don’t want to grow old

In this eternal damnation.

But everyday the pain deepens

As I daydream about being free,

But it feels as if I’m sleeping,

Please, can somebody pinch me?

They Don’t Really Know Me

by Dexter Ragland

Everybody judges me in a particular way because I’m a six-foot-four, 350-pound black man. But they don’t really know me. The reason I’m taking this class is because something happened to me when the NPU gospel choir came. I was changed—and I want to explore that.

On Beauty

by William Jones

Beauty—It’s walking down the street of your community feeling the power of love flowing from each house you pass. It’s knocking on any door and being accepted by the inhabitants. It’s seeing children roam the streets without fear of being harmed. It’s seeing newlyweds moving into their first home in with high hopes for the future. It’s hearing the bells of the church ring and people of all races coming out of their homes to attend together.

Beauty. It’s knowing that Jesus Christ resides in the heart of every community.

The Cemented Coffin

by Marcos Gray

The cell I reside in has nothing lavish about it. It’s a cemented coffin, I’m its breathing cadaver. The furniture is a steel sink connected to an industrial toilet, which could probably flush a small animal. The bunk beds are steel with a mattress so thin that it only slightly adds a modicum of comfort. If you’re on the top bunk where I reside, there is hardly enough space to sit upright without slouching down. There is a desk and a stool welded to the wall and floor.

The drab gray walls have many patches missing, revealing black molded pockets. The bars that operate as doors are rusted, revealing how antiquated this 100-year building is.

But the discomfort inside this coffin is only a microcosm of the discomfort of my imprisonment. Each inhalation of oxygen is like chewing shards of glass. I write to battle the feeling of being stranded on a deserted island.

Yet I am never physically alone inside this cell—the mice and roaches languish here with me. (The psychological isolation is another matter.) Were they sentenced to life without parole at age sixteen like me?

Even worse, the birds have constructed nests here. It’s as if they’ve acquiesced to a life behind barbed wire and steel fences. Their self-imposed confinement seems to have faded their natural beauty—just as Stateville’s prisoners have lost theirs.

This dilapidated coffin attempts to negate my worth. Yet I believe this place can either be a womb or a tomb. Despite my deathlike confinement, I try to see it as a womb—a place of rebirth, giving me life I can share with others.

Molded into His Image

by Ryan Miller

Why does black faith matter to me? To be perfectly honest this is a very uncomfortable question for me.

When this class first started, I had no idea how I could possibly contribute, but I figured, “Hey, if a white woman could teach this class, then as a white man, I could at least participate and learn.”

As the class progressed, I noticed a common thread in the literature we studied—the idea of redemptive suffering. It’s a concept the entire class understands, especially my fellow incarcerated classmates. My hope is that the suffering of those in prison, for example, can reveal the evils of the system to those on the outside.

Our response to suffering can be a catalyst to redemption. “Consider it all joy…when you encounter various trials, knowing that the testing of your faith produces endurance. And let endurance have its perfect result, so that you may be perfect and complete, lacking in nothing” (James 1:2-3). The Scriptures are clear that we have a Creator, Savior, and High Priest who can relate to our sufferings (Hebrews 5:8).

The more I go through, the more I study, pray, fast, and draw closer to my Savior. I’ve come to see suffering as a chisel that the Messiah uses to chip away at me as he molds me into his very own image.

The Eye of the Beholder

by Michael Sullivan

As a child, I watched lots of television and played video games for hours at a time. It taught me that beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Of course that beholder was the corporations that programmed the games, convincing me that beauty was something that gives pleasure to individual sense organs, mainly our eyes. As I matured, I began to question how much truth and goodness there was in virtual reality.

Today I see beauty as a bridge between truth and good. It’s a tool used to care and create for humanity. It connects the outer world to our inner world. Beauty is a divine treasure, a godly gift.

Restoring Hope

by John E. Taylor

Prior to taking the Urban Studies class, I didn’t see institutions as part of the problem that keeps us divided into an “us and them” society. But I learned that true community doesn’t seek to divide us; rather, it brings us into harmony with each other. True community is a genuine representation of what it means to be Christ-like.

My education is helping me to be a better minister inside of prison for my fellow inmates and to various officers who confide in me with their personal struggles on the outside. This class has redefined my vocation by reminding me that evangelism is still a part of my ministry. I fully embrace the belief expressed by the authors of And the Criminals with Him that “freedom is in Christ” and Christ alone. If I’m going to be an effective father to my twelve-year-old son and minister to my fellow inmates and the officers, I must let them know that real liberation isn’t in things or men or women, but in Christ Jesus alone.

The vicissitudes of life bring about so many discouraging moments that can break down those around me who each need a word of encouragement. This class—the instructors, the reading materials, as well as my fellow students—has revived my calling to be an encourager.

Recently my son received Fs in four of his classes. Initially I couldn’t wait to lay into him the way my parents would have done to me. Yet I noticed the patience of both professors as they each listened intently to us. They demonstrated community, as well as encouragement. Now I definitely will have a different approach with my son.

I thank God for allowing the administration, North Park Seminary, and our professors to offer us the greatest educational experience I have had in prison. My life has been forever changed because of my experience in this class. It restored a new sense of hope and clearly defined my vocation/ministry inside and outside of prison.

Why Does Black Faith Matter to Me?

by Corzell Cole

I was born during the crack epidemic in May 1983. My father had been battling addictions for more than thirty years, so he was never really part of our household.

Statistics show that once fathers are removed from black households, their sons’ chances of graduating from high school decline drastically. It took me more than two decades to truly understand the impact of my father’s absence on my life. Though he still struggles with addiction today, I understand now that the damage done wasn’t necessarily his fault.

After serving ten years of a fifty-year sentence, I reunited with my father. In 2013 I told him face to face that I forgave him. He looked me in my eyes while under the influence of some substance and told me, “You’re a better man than I’ll ever be.” Experiencing things like this from birth until now made me the man I am today. Faith pushes me forward.

I inherited much of my faith from my mother. She had to work two, sometimes three, jobs to try to make ends meet.

Before I could understand the true struggles of being a single mother with three kids to feed, I wondered why we had to suffer. Why didn’t we have a big house with the dog and the white fence? My mother would say, “The Lord has big plans for us.” Many times I witnessed her on her knees praying. My mother’s faith saved me.

Throughout my childhood, I experienced a lot of trauma, some of which still affects my mental functions today. From drug deals to shootings—I was exposed to these types of activities at three or four years old.

At eight years old, I was a victim of a random act of violence that changed my life. I was struck by a stray bullet that was fired from a gun into the project apartment we lived in. The bullet entered my left arm then traveled through my left side and exited my back. My lungs collapsed twice—both times I was resuscitated.

Afterward, even my ability to play sports was impaired, and I fell behind in my schoolwork. I was never provided counseling or any type of mental health treatment. All I had was a faith-driven mother who stood by my side.

Throughout the thirty-three years I’ve been on this earth, I’ve learned many valuable lessons, but being in theology class has helped me spiritually, mentally, and emotionally. It’s almost as if the reading and the dialogue is the theology I never received as a child. When I read, Can I Get a Witness? I saw my mother in the pages. A Fire in the Bones, by Albert Raboteau, educated me on a number of different things—from slavery to how African Americans had to fight not only for freedom but for every other thing imaginable. The Cross and the Lynching Tree, by James Cone, opened my eyes to how slavery is still present today in mass incarceration.

My reflection is based more on why all lives matter, and why everyone’s faith matters. As I embrace my own growth, I can only attribute it to the overwhelming love of Christ.

So the question, “Why does black faith matter to me?” is easy to answer, but I want to switch things up a bit. Why does your faith matter? Our Lord and Savior doesn’t see color, so why should we?

The Sound of Stateville’s Invisible Church

by Demetrius Cunningham

No chains can hold me. No boundaries can stop me. I’ve made my mind up, I will never give up, cause I can’t get enough of Jesus. He promised me, brand-new mercies, will kiss and wake me, and every moment is a brand-new day. With his power, I will conquer. Every hour, his love will shower. Light the world up, cause we’re taking over. Every dark place, we’re going to fill with his grace. Everybody say, “Oh, I see Jesus.” Everybody say, “Oh, he’s everywhere, he’s everywhere.”

These are the words of “He’s Everywhere,” one of our freedom worship songs that we sing in Stateville.

Our worship contains an intense drive and determination. We have created our own innovative worship songs. Worship becomes our attempt to fight against the deep darkness of our environment. We release the light of Jesus Christ to defeat the evil aspects of this place. Our songs release healing and salvation into the atmosphere—not just for the residents, but for the staff also.

Prison communities and the communities that incarcerate people represent both suffer from the same social, economic, and political problems—from violence and poverty, to health care and education.

We decided to pick up this torch and use our worship music to fight for freedom and equality—not just for black communities and prison communities, but for oppressed people all over the world. And even though our voices are often muted, we still believe that we can be heard.

This is not the end, it’s the beginning of the next chapter. God is preparing an army of believers inside and outside of prison. We are called and gifted with music and songwriting to continue the fight for freedom and equality. We are men, women, and children of many cultures and ethnic backgrounds. These precious treasures passed down to us from generations of African and African American ancestors are vital to our communities, our struggles, our survival, and the world.

Fearfully and Wonderfully Made

by David Carter

Before you were even born, God knew you. Finding your purpose is a lifelong journey, but you can miss it if you don’t seek God’s plan for your life, asking him daily to reveal it to you.

Once you have discovered your purpose and have chosen to do the will of God, it’s like an itch you can’t quite satisfy. You live every day on purpose and with a purpose.

In my life’s journey my eyes have witnessed so much, starting at a tender age—things no human being should ever have to see. I’ve seen things I wish I could have prevented or changed. When I look back, I realize how ignorant and cowardly I was for failing to do my part to protect my community, especially the elderly, the young, and women.

Most of us carry emotional, physical, and/or psychological scars with us—but the psychological scarring stays with us, sometimes causing us to make decisions we wouldn’t make otherwise. Some of us use that pain to propel ourselves to great heights; some use it for self-destruction. I have done the latter.

Now let me tell you how good God is. He has allowed me to be awakened as a man. Through much prayer and reflection, through trusting and believing, I have begun to heal and mature by God’s grace. I have learned that you must first ask God for forgiveness, and then you must forgive yourself. Prayer works, and forgiveness heals.

I believe that God has allowed me to experience the prison industrial complex to prepare me for the ministry of restoring people like myself to useful citizenship. I want to be able to lead people to economic institutions that can provide them with money, jobs, food stamps, clothing, housing, and healthcare upon their release.

I want to somehow show our citizens who frown upon ex-offenders the benefits of proper use of their hard-earned tax dollars that can reduce recidivism rates if we are willing to educate and provide jobs for all our citizens, including ex-offenders.

This is a formidable but doable task, and the results can be permanent and meaningful. When people have jobs, they will be able to purchase their own goods.

I believe my purpose in this life is to make a difference in a positive way in my family, community, and my surroundings. Even though I am sitting in a prison cell as I write these words, I understand how truly blessed I am because of God’s love. I have conquered and I have survived. Life is a lesson, and I have learned so much along the way, and I am still absorbing and growing.

Why Does Black Faith Matter to Me?

by Christopher D. Everett

As a child, I was tormented by something evil as I slept. I was afraid and terrified. There were moments when I couldn’t even speak or cry out for help. This went on for years until one night I called out for my grandma.

I didn’t know it, but that became a turning point in my life. My grandma taught me to call on the name of Jesus. For the first time, I found power over my fear. Hallelujah! The power of that name gave me strength through the night as his angels comforted and ministered to my spirit. I know I am alive today because of God’s grace and the power.

Why does black faith matter to me? This question is simple and complicated at the same time. On one note, black faith shaped a people who were so downtrodden that they likened themselves to the people of Israel in bondage and created a symbol of hope for the world to see. The Lord called those who were broken and spoke into their brokenness, saying, “Be whole” and they were made whole. So they called on the name of the Lord and taught it to their sons and daughters. They sang, “Kumbaya, My Lord” and “We Shall Overcome.”

Black faith matters because it revolutionized praise and worship in the church. It gave a new meaning to the words “Dance like David danced.” Black faith has played a role in the way we say “hello,” the way we eat (“soul food,” or food from the soul), and the way we show forth the reality of our true selves. It has encouraged generations to embrace who they are while striving all the more to reflect the Christ who lives within them. Black faith has in some way affected nearly every genre of music and dance since the 1920s and continues to shape and reshape the church and culture today.

Black faith has transformed tragedy into the glory of rebirth bearing redemptive properties through the suffering that caused a people to hope. As the Bible says, “And hope does not disappoint us, because God’s love has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit who has been given to us” (Romans 5:5). This is the source of black faith, for I AM has spoken, saying “Behold, I am the Lord, the God of all flesh, is there anything too hard for me?” (Jeremiah 33:26). This is why black faith matters to me—and to so many others who recognize the God of Israel.

A Clearer Vision

by Senequ Thomas

From the first beat of my heart, the path of my life was paved. Along my journey, there were signs posted: Stop. Go. Turn right. U turn. Yield. These were my choices as a youth growing up in a low-income area that was full of poverty and drugs.

As a child all I knew was I had everything I needed. I had food, toys, and friends to play with. I didn’t know how hard it was for my family to keep food on the table, the house at the right temperature, clothes on my back, and to make sure I was raised right.

Then in one turn of events, my life changed and I ended up in prison. Here, more decisions had to be made. The most important one was my kids. Who will provide for them? Who will protect them? Who will love them as only I could?

When we make choices in life, too often we fail to consider the consequence of our actions. Yet I have become a person with a positive outlook on life, a person who is there for other people. I have learned what it means to be a man, a son, and a dad—but what is odd is that all these things had to be taken out of my life for me to truly understand their importance.

The choices I make—the growth, the loss, the love and the pain, the joy, the sorrow, the laughter, the knowledge, the wisdom—all of these things define who I am, so my purpose in life is to be “Senequ.” My purpose is to be a man who continues to live, to be a father who continues to be a dad to his children regardless of his situation. To be a son to his parents who created me and gave me the best guidance they could.

As I look up at the TV, a commercial for Black Lives Matter comes on. I ask myself why should anybody have to be informed that Black Lives Matter? And I have to ask another question: Black Lives Matter to who? That leads me to ask, who does my life matter to? Who am I important to? This makes me re-evaluate all I’ve done and all I have become. I realize that I need to correct my steps by living for others, forgiving those I have yet to forgive and replacing all hatred, known or unknown, with nothing but love!

I aim to be a blessing to the people in my life. This class has awakened me to a clearer understanding of who I am and what I wish to become. Just when I thought I had it all figured out, I realize I could be so much more. Thank you for giving me a clearer vision.

How God Got My Attention

by Marcos Ramirez

I was born October 11, 1977, and raised in the Wicker Park and Humboldt Park neighborhoods of Chicago. I have a Dominican father whom I’m named after, a Puerto Rican mother, a younger sister, and a younger brother. We grew up in a four-apartment building complex with a grocery storefront that my grandma owned and operated through my aunts and uncles. I was very family-oriented and since we pretty much served our community via the grocery store, I got to know many of the people who lived in the East Village community. I was naturally a people person.

My favorite pastimes were when all the family would come together at Thanksgiving and Christmas to feast on traditional Puerto Rican, Dominican, and Cuban foods and dance to the latest salsa y merengue jams, and when summertime came around, the Puerto Rican parades and Humboldt Park carnival rides, music, and foods with all the people rejoicing. Along with these, family vacations to La Isla del Encanto have created some of my best memories.

The paradox of my life is that along with the best memories came some of my worst experiences—living under the tyranny of a strict and abusive father, I had a childhood riddled with many hardships. My parents argued and fought a lot, and the physical and mental abuse that we all suffered caused me to become rebellious and very angry as a young teenage boy. In high school I began to smoke weed, drink liquor, sell drugs, carry guns, and get involved in the party-crew mob scuffles that often occurred in the school hallways, escalators, and outside grounds.

I began to have little run-ins with the police, a precursor to the years that would follow after I graduated from high school. Although my dad was very harsh on me, he did generally keep me off the streets. But when he got locked up right before I graduated, all hell broke loose with me and I went out doing just about whatever I felt like doing, which was gang-bang and sell drugs.

My attitude and lifestyle caused me to get shot in the summer of 1996. While lying in a hospital bed I experienced my first memorable encounter with God when a strange man dressed in black entered the hospital room and told me that God was calling me. I don’t remember the man’s face, what he looked like, or whether he was a priest or not. All I remember was freezing up and literally not being able to consciously move in the presence of that voice.

That same summer I met a girl who later bore us two sons in 1997 and 1999. I worked while hustling on the side to make ends meet and help raise our boys. We fought and argued a lot like my parents used to, and I became abusive like my father was, and I cheated on her like my dad did to my mom. Basically I became much like the man I had feared and hated all of my childhood years and I hated myself for it.

In 1999, I received a class I felony drug charge and a class X armed violence with possession and intent to distribute large amounts of cannabis. I lost $15,000, along with my apartment and everything I had built up over the last year and a half. I fell into a deep depression where I was struggling to get back on my feet while facing six to thirty years in prison. I was self-medicating with weed and drinking a lot. The pressure of not being able to take care of my own family, plus the ongoing domestic drama and the life-threatening beef I had on the streets with past gang altercations had pushed me to the limit.

I wanted to give up. Crying and saying that I couldn’t take it anymore, I held a loaded .44 magnum with my finger on the trigger pointed up into my jawbone. My sister called the police and my brother tried to take the gun away from me, crying and begging me not to do it. As I saw my life flash before my eyes, God allowed me to “see” myself in a casket with my family and my sons crying around my lifeless body. I cried all the more, unable to bear the weight of putting my family through that type of suffering. So I did not pull that trigger, and the police came and locked me up again.

After counseling, I opted for court-mandated boot camp on the two drug cases (one of which was lowered to a class I), and I spent the next five months undergoing rigorous training exercises and routines that became a huge blessing for me. In Cook County Boot Camp I first accepted Jesus Christ as my Lord and Savior. Right then, I felt a heavy load getting lifted off my neck. I felt free in my spirit and soul!

I started reading the Bible and praying every day. I moved forward and grew as I took anger management, time management, and basic computer skills while in the boot camp. My drill instructor, who was a sergeant in the Marine Corps, taught me a lot about discipline and paying attention to detail. He taught us about being thick-skinned like the rhino (which was the mascot our platoon adopted) and charging forward to face obstacles in our lives. He even chose me to be one of the squad leaders in our Echo-6 platoon, where I was given the responsibility of leading a group of about eleven “rebellious” men.

We graduated from boot camp in the summer of 2000, and I came out a new man with a positive outlook on life. But I made a big mistake when I took house arrest at my mom’s apartment back in my old ’hood instead of at my girlfriend’s apartment with my sons on the North Side. In the ’hood all of my old acquaintances were still doing the same things I was doing before I got locked up. I didn’t take house arrest at my girlfriend’s apartment because she had told her landlord that I was in the Army instead of at Cook County Boot Camp, and I was afraid of exposing her fib when a Cook County sheriff’s car pulled up to see me. I thought she could lose the place on my account so I opted for a one-month stay at my mom’s. While at my mom’s I had many visitors who offered me a slew of temptations, and I made several bad choices.

Gradually I stopped reading my Bible and praying, and turned my back on God. One year later, I almost died in a fire with my girlfriend and our sons. The same day my forty-year-old aunt died, and I lost my job with the Electrical Union. I ended back on the streets selling drugs again—and then in jail with a death penalty looming over my head.

That’s where God really got my attention. Four months into my stay I decided to renounce my gang affiliation and rededicate my life to God. I began attending daily Bible studies and group discussions. I started to draw closer and closer to God through prayer and fasting, studying and meditating on the Scriptures. We fellowshiped, praised God, and worshiped in group settings, as well as individually within our cells.

Without even trying, I stopped using foul language and even my walk changed. I no longer thought, spoke, or acted like I was tough. I even found myself forgiving my dad and others who had hurt, betrayed, or offended me in the past. God began to teach me many different things, like how to listen, be patient, understanding, and compassionate toward others. He taught me how to be a loving father by his own example as my spiritual Father and how to be a loving husband by the example Jesus gives in how he loves the church. He is now teaching me how to listen for his voice by being still in my spirit and soul and how to wait for him.

I’m certainly a work in progress as he guides me and directs my steps. By God’s grace and his anointing upon me, I led several men to Christ at the jail, and by my living example of Christ-minded devotion, the Spirit led my mom and two sons to accept Christ as well—all to his glory, not mine, because all I did was look to Jesus—he did the rest. Hallelujah!

I am going to school and taking as many classes as I can to help me prepare for a successful reintegration. I’ve been doing advocacy work since 2012 for prison reform, restorative justice, police misconduct issues, violence prevention, and other practices, seeking to transform prison culture and public perceptions through peer education and collaborative efforts with any outside supporters who are willing to help us achieve these goals.