[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row el_class=”hero-header-text”][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Reimagine That

Theological Education: Seminary Disrupted

by Kurt N. Fredrickson | January 9, 2017

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

In the past, at least for those in denominational churches, the path toward becoming a pastor was well rutted: graduate from college, move to the seminary of choice, go to school full-time, work a part-time job, get a master’s of divinity in three years, and then start working in a church in your denomination. That was true for me, and for all my pastor friends in our generation.

This is no longer the case.

A good number of seminary students still work toward theological degrees, but now, more are opting for a smaller (i.e., shorter) master’s degree, rather than an MDiv. Students are taking longer to get their degree, juggling work and family along with their education. A good number of students are older, getting a formal degree after years of being involved in full-time church work. They are less willing to move to where the seminary is located, opting instead to take many of their courses online.

A number of students will do their ministry work outside of traditional church settings, and students who do pursue work in a church are less likely to be connected to a particular denomination. Many will serve in nondenominational and nontraditional settings.

Another interesting note: a growing number of ministry leaders have little or no formal theological training. This is especially true of pastors who work at very large churches, and those who are involved in church planting.

Some students will do their ministry work outside of traditional church settings, and those who do pursue work in a church are less likely to be connected to a particular denomination.

Beyond how leaders are getting trained, new forms of church are emerging. While traditional brick and mortar churches—both large and small—are still found throughout the country, there are also storefront churches, video-fed, multi-site churches, house churches, pub churches, and marketplace venues. These congregations are located in inner cities, suburbs, and rural areas, and they have their own unique characteristics and challenges. Pastors serve full-time and part-time. And some—by choice or by necessity—serve bivocationally.

Whatever the shape of the work of ministry, it is an important calling: Ministry leaders influence the lives of people, local congregations, and society in significant ways. The work is demanding and challenging. Ministry leaders want to do this work well. And so, ministry leaders need good theological training.

We Need Well-Trained Leaders

Every year I get a health checkup with my physician. I want to stay healthy. And when I get sick, I go back to my doctor in order to get well. I put a lot of trust in my doctor. I want a physician who is well trained and who will serve me well. My health is just too important.

Every year I get a health checkup with my physician. I want to stay healthy. And when I get sick, I go back to my doctor in order to get well. I put a lot of trust in my doctor. I want a physician who is well trained and who will serve me well. My health is just too important.

The work of ministry is also important. The church needs well-trained and well-formed leaders.

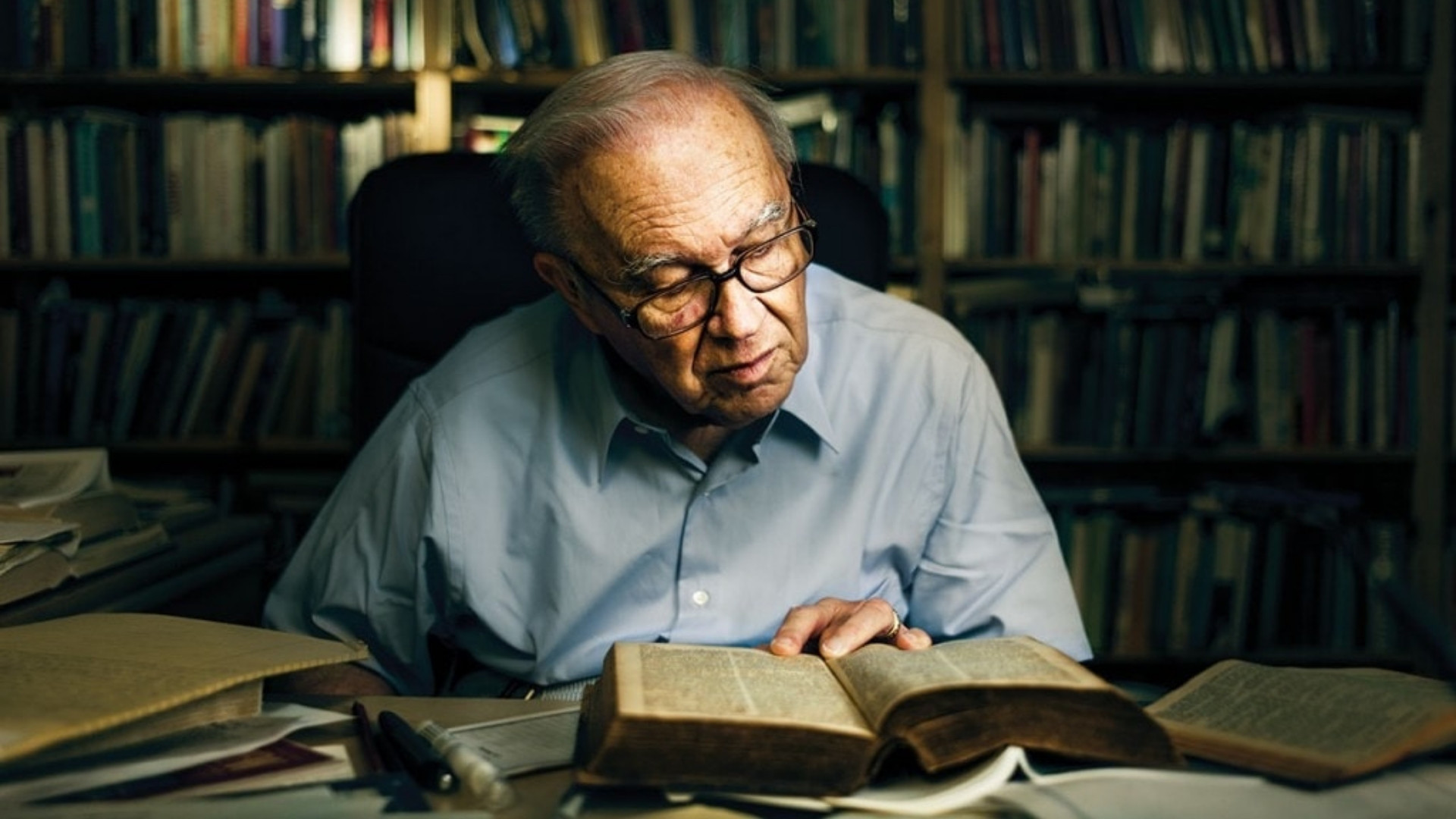

Ray S. Anderson, one of my professors at Fuller Theological Seminary, wrote, “Whether we realize it or not, every act of ministry reveals something of God. By act of ministry I mean a sermon preached, a lesson taught, a marriage performed, counsel offered, any other word or act that people might construe as carrying God’s blessing, warning, or judgment.”

Anderson was saying that pastors must do their work with great care and diligence. Whether right or wrong, ministry leaders through words and actions often become God’s representative. People rely on us, trust us, and put their confidence in us. Pastors have a great deal of influence in the life of a local congregation. They must do their work well, and this requires good theological training. But that does not necessarily mean getting a master’s degree from a traditional seminary.

The question is, in a changing world and an increasingly diverse ministry world, how do we reimagine theological education? That includes reaching a world that has seen the rise of the “nones,” people who consider themselves religiously unaffiliated. A Pew Research Center poll conducted in 2012 found that only 10 to 12 percent of nones are looking for “a religion that is right for them.” Eighty-eight to 90 percent are not. Our old build-it-and-entertain-them model of doing church doesn’t work anymore—if it ever did.

The church, in its many emerging forms, and those who lead these churches, set the agenda for ministry training. Theologian Craig Dykstra of Duke Divinity School helps imagine this reshaping of the agenda with three questions: 1) What is God doing in the world? 2) What do churches need to become to join God’s mission in the world? 3) What do seminaries need to become to equip the church to join God’s mission in the world?

These are tough questions! Honest answers will push churches, schools, and denominations to recast what theological training will look like in the future. The path forward is uncertain. A lot of assumptions and current practices get challenged. Of this I am certain: Seminaries of the future will not look like seminaries of the present, nor the past. Courage and innovation are required.

Theological Education in the Future

Here are some guiding thoughts as we face the challenges ahead.

The mission of the church in the world must be the heart of theological education. As South African missiologist David Bosch said, “Theology ceases to be theology if it loses its missionary character.”

Character formation and ministry action are essential aspects of theological education. The outcome of theological education is not simply graduate-level knowledge. Princeton Seminary professor Darrell Guder notes that the outcome of good education is, more importantly, the formation of ministry leaders and their impact on the communities they serve. Author Rachel Held Evans reminds us, “Millennials aren’t looking for a hipper Christianity….We’re looking for a truer Christianity, a more authentic Christianity.”

Earning a graduate theological degree should not be the only path toward recognition of competence for ministry. Seminaries in partnership with churches and ministry organizations must create new avenues of training that are both theologically reflective and practical. This raises the question, what is required in order to be ordained by a church body? Is it necessary to earn a master’s degree?

Theological education must be affordable and accessible to ministry leaders who are unable to pursue graduate studies. Not all ministry leaders have had the good fortune to be able to get a college degree and afford the high price of a traditional seminary education. How do we make theological training available to a wider number of called and gifted ministry leaders?

Theological education must extend to those who serve beyond the church. That means professionals in the marketplace, artists, musicians, and laity. Fuller Seminary missiologist Wilbert Shenk writes, “The strength of a movement is in direct proportion to its ability to mobilize its total membership.”

Theological schools must train ministry leaders to serve the emerging world. A student must never say, “I was trained to serve in a world that no longer exists.” Ministry training, while being theologically robust, must also be culturally and contextually relevant and practical.

Professors in theological schools must encourage students and emerging ministry leaders to imagine new forms of ministry. Professors must push students toward ministry innovation, even beyond where professors are comfortable.

Both Anchor and Sail

Reimagining theological education requires what L. Gregory Jones, provost of Baylor University, calls “traditioned innovation.” We appreciate and learn from our traditions as we move in new directions.

David Nyvall, founding president of North Park University and Seminary, used a nautical image to illustrate: “On a well-equipped ship there is an anchor as well as sails. They both serve the welfare of the sailor, the anchor insuring his conservation, his safety, the sail provided for his progress, including his goal, his home. The anchor does not mean rest, and the sails do not mean unrest….I would hate to sail without an anchor, and certainly I cannot sail with the anchor alone. Sails and anchor are one in purpose, largely. Sails make the anchor very much needed, and the anchor makes the sails very much wanted.”

Theological education in the future will look different than it does today. We need anchors and sails in order to serve the current and future church well.

Tags: Reimagine, North Park

[/vc_column_text][vc_empty_space][/vc_column][/vc_row]