[vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

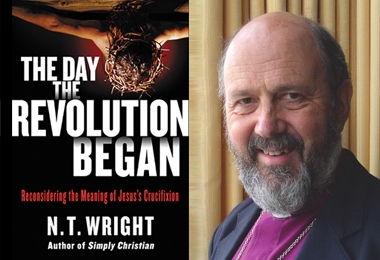

The Day the Revolution Began

N.T. Wright

HarperOne, 2016

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

Reviewed by John E. Phelan Jr. | June 21, 2017

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The cross has always been a problem. One does not expect, to say the least, one’s Messiah to be crucified! Christians throughout history have struggled to make sense of Jesus’s brutal death. Their explanations are often called “theories of the atonement.” Most of these theories focus on the individual: how does Jesus’s death impact me, save me?

N. T. Wright would suggest that viewpoint rather significantly narrows our angle of vision. Jesus’s death, Wright argues, actually launched a revolution and as individuals we are a part of that revolution. In fact, “having been put right” we have “become part of God’s plan to put his whole world right.” The cross is not just about saving me—it’s about renewing the world. Jesus’s resurrection launched a new creation—his resurrection was the first resurrection of the last great resurrection.

Followers of Jesus live from this new life and join God’s purpose to make all things new. “If anyone is in Christ,” Paul wrote, “the new creation has come” (2 Corinthians 5:17).

That suggests that some of the most popular interpretations of the cross are, to say the least, problematic. In the penal substitutionary approach, Wright contends that instead of “God loved the world so much that he gave his only Son,” as in John 3:16, it can seem to say, “God so hated the world, that he killed his only Son. And that doesn’t sound like good news at all.”

Wright continues: “If we arrive at this conclusion, we know we have not just made a trivial mistake that could easily be corrected, but a major blunder. We have portrayed God not as the generous Creator, the loving Father, but as an angry despot. That idea belongs not in the biblical picture of God, but with pagan beliefs.”

In The Day the Revolution Began, Wright does what he does so well in his many books. He sets the cross in the context of its Jewish and Greco-Roman worlds and rigorously explores the key New Testament texts addressing the ultimate meaning of Jesus’s death and resurrection. Commenting on Galatians 3:13, for example, Wright insists that when Jesus redeemed us from the “curse of the Law” Paul was not saying that “‘The Messiah became a curse for us so that we might be freed from sin and go to heaven,’ or anything like it. He says in verse 14 that Messiah bore the curse of the law, ‘so that the blessings of Abraham could flow through the nations in King Jesus—and so that we might receive the promise of the spirit through faith.’”

He continues: “Paul is not saying that the Messiah’s death rescues people from hell. Nor is he saying that it brings humans back into fellowship with God. These are important, but they are not the point he is making. Galatians 3 as a whole is about how God’s promises to Abraham have always envisaged a worldwide family and how the gospel events have brought that into reality. The death of Jesus launched the revolution; it got rid of the roadblock between the divine promises and the nations for whom they were intended.”

This is a wonderfully rich and provocative read. Some years ago J. B. Philips wrote a book entitled Your God Is Too Small. This book could be entitled Your Cross Is Too Small. Our individualistic views of the atonement and, for that matter, the gospel, don’t begin to do justice to the full implications of the New Testament understanding of the implications of Jesus’s death and resurrection.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]