Stories of Grace and Resilience in Rural Churches

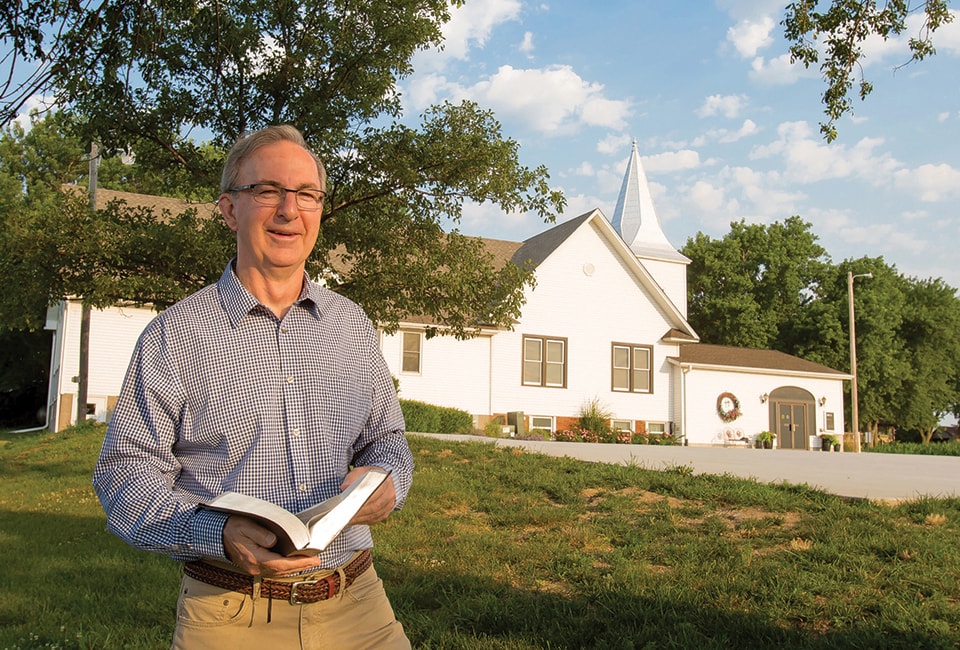

by Bob Smietana | Sept 6, 2017 | Photo credit: Elisabeth Fondell

Steve Hoden never knows what to expect when he walks in his front door. There could be fresh vegetables on the counter, a pot of soup in the fridge, or some chickens in the freezer. As long as the chickens aren’t running loose in the kitchen, it’s all good.

“I just tell people I’m glad the chickens aren’t alive,” says Hoden, pastor of Salem Covenant Church in Oakland, Nebraska, population 1,198. “In the old days, they’d bring you some chickens, a milk cow, and a couple of pigs and that’s how you got paid.”

It’s the small things, the everyday acts of kindness, that make rural ministry so rewarding, says Hoden, who’s been pastor at Salem for more than fourteen years.

Hoden, a second career pastor, doesn’t mind working far from the spotlight. Instead, he is often amazed by what God is doing in his congregation and community.

The church supports missionaries, helps sponsor a medical clinic in Congo, and donated more than $13,000 to people in need last year. And new people—many of whom haven’t been in church for years—are showing up at Salem, where they feel welcomed without being criticized or judged.

Despite a drop in local population—the county lost about 12 percent of its residents in the last decade and about a third of the population in the last fifty years—the congregation has remained constant at about ninety people.

“In our county, that’s like church growth,” says Hoden.

Popular perceptions of rural America vary widely—from images of God’s country, where everybody goes to church and loves Jesus, Mom, and apple pie, to scenes of despair and decay, where populations and services are declining and drug use and unemployment are increasing. The truth is somewhere in between.

Some rural communities are struggling. Some are thriving. Some are growing while others are shrinking. And while most people in rural America say they believe in God—many never darken the door of a church. That’s the case in Riley County, Kansas, home to Alert Covenant Church. Only about a third of people in the county have ties to a church.

“There are a lot of people here who say, yes I believe in God,” says Dwight Diller, pastor of Alert Covenant. “But they aren’t engaged with a church.”

Alert Covenant has experienced a slow but steady growth in recent years. But that wasn’t always the case. Back in the 1970s, the church was small enough that it shared a pastor with another small congregation in nearby Clay Center, about fifteen miles away. Today both churches are thriving.

Diller has been pastor at Alert for more than two decades. It’s the only church he’s ever served.

When he arrived, the church had about 100 people. Then, in 2009, the church set a goal to double their attendance. As part of that process, they added staff

and built a new sanctuary. In two years the congregation had welcomed fifty new people—a pretty impressive accomplishment in an area where the two closest towns are Leonardville, population 400, and Green, population 150. Things slowed after that. Every year a few new families come, a few leave, and today the church

has settled into an average attendance of about 140 on a Sunday.

“We have worked really hard to try and attract families,” Diller says. “That’s where we’ve seen the most growth.” Folks now come to church from about a fourteen-mile radius.

Still, there are more people they’d like to reach. One of the big challenges is connecting with those who don’t attend church even though they believe in God and say they are Christians. “There are a lot of people we could be reaching,” Diller says.

Like every church, Alert has its struggles. A number of people from the congregation drive to Manhattan, about thirty-five miles away, for work, so they’re less likely to have time for small groups or other church events or ministries during the week. People—even out in the country—are always busy, says Diller.

There are other issues. The divorce rate is high. Meth use—a problem that plagues many small communities—is an issue. Jobs aren’t that plentiful. The local food pantry, run by churches, serves about twenty-five families a week.

Still, there are benefits to rural life. Diller says he appreciates the connectedness of his small town, where everyone knows their neighbors and is willing to lend hand. In their church, some members have three generations worshiping together. “The community is family oriented, and so is our church,” he says.

The revival of Clay Center Covenant Church started with kindness, prayer, and a few tasty treats from a local bakery.

In 1977, Beth and Maury Catlin, a newly married couple who’d just graduated from Kansas State, arrived in Clay to teach at the local high school.

They began attending the Covenant church, where nearly everyone was in their seventies. Leland Anderson, a retired missionary, was the pastor. Every Sunday he’d preach a sermon, then jump in his car and drive fifteen miles to Alert Covenant Church, his other congregation.

There were few other young couples, yet the Catlins felt at home. Anderson’s sermons were plainspoken and filled with kindness; the congregation was warm and welcoming. One of the older couples befriended the Catlins, who had no family nearby, and often invited them to their home for dinner.

Beth Catlin says she knew that Clay Center was her home not long after their son Ryan was born. He was crying one day in church and she got up to leave. Other church members told her to stay.

“It sounds so good to hear a baby in church,” one of them told her. “We have not heard that for so long.”

By 1980, the church had started to grow. When the Catlins’ second child was born, there were five kids in the children’s program.

Other young families began showing up, a number from a small Bible study that met in a local bakery. The Catlins and some friends from town started meeting there, including the bakery owner. Eventually most of the folks from the group joined the church. They wanted their kids to grow up in a church that would love them and nurture their faith.

Within a few years, the tiny church was overcrowded. So they set up a television in the basement and piped in the service. Newcomers went up to the sanctuary, while the regulars watched in the basement. Anderson did all the small things to make people feel welcome. If someone was missing, he noticed. And the older people in church took the new people under their wing.

After Anderson left, a new pastor, Brian Johnson, helped the church continue to grow. They built a new building in the 1990s, then added on to it. Today Grant Clay is pastor, and they’re a congregation of about 400 people, which brings challenges of its own.

“When you get to a certain size, you lose that sense of family,” Catlin says.

Recently retired from teaching, Catlin says her next job is to make sure that every newcomer feels just as welcome as she did forty years ago. “When someone walks in the door, we want them to know we care,” she says. “You can’t hire someone to do that. You have to have all the people in the church welcoming them.”

Clay Center Covenant also continues to reach out to the community, where there’s poverty and meth, broken homes and unemployment—many of the same problems that cities face. And many people feel disconnected from each other.

“We have a mission field right here,” Catlin says.

Brad Thie, director of the Thriving Rural Communities Initiative at Duke Divinity School, says he’s seen a change of attitude in pastors toward rural ministry. In the past, he says, rural ministry was either a dead end or a stepping-stone. “Rural ministry was a place you served time until you went to somewhere more important,” he says.

Today he’s seeing more pastors interested in rural ministry as a lifetime calling. Every summer Thie oversees student interns at small churches in North Carolina. For many, it’s their first taste of ministry. They come from urban or suburban places, then head out to a rural church, where they do their first sermon, or their first funeral.

Most are surprised by the welcome they receive, says Thie. “They find themselves overwhelmed by the love, the experience of community, and the giving nature of people who live in those spaces.” he says.

That doesn’t mean everything goes perfectly. Diversity, especially in the South, remains a challenge. “We still are struggling with racial reconciliation and a deep history of racism,” Thie says. “At times, our local congregations prove to be the exception to that narrative.”

And small-town churches—like other aging congregations—can struggle to pay the bills as their membership shrinks. Still, he’s hopeful for the future of rural churches.

“As long as Jesus is resurrected from the dead—we ought to be hopeful for rural and small-town churches,” he says.

Gil Waldkoenig, director of the Town and Country Institute at the Lutheran Theological Seminary at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, is also optimistic about the future of rural congregations. “Rural churches are…resilient,” says Waldkoenig. “They are going to last.”

One reason is the strong sense of community that’s often found in rural churches. Waldkoenig says rural churches see themselves as families, and members feel a sense of loyalty and commitment to one another.

He identifies two kinds of church in the United States. One is the “traditional style of community,” which resembles a family or tribe. The other is a voluntary association, where like-minded Christians come together to form a church.

Most rural churches fall into the family or tribal model, Waldkoenig says. That can make them less likely to splinter when people disagree with each other. And in some cases, there are two or three generations of the same family in the church—and people tend to stick with these churches over the long haul, even if they don’t always see eye to eye. They have stability that can be lacking in churches built as voluntary associations bound by doctrine or practice. “In families you can fight like cats and dogs, and still stay together,” he says.

Rural churches are resilient. They are going to last.

Hilmar Covenant Church, a congregation of about 180 people, located in central California, is known for its love for missions, its generosity, and its close-knit community. It is also showing how people can have conversations about potentially volatile issues.

On Wednesdays, the church hosts what it calls “Fika,” a coffee hour for people to get together and discuss whatever is on their minds. These days, it’s often politics. And like most Americans, members of Hilmar Covenant have strong opinions—and they often disagree with each other, says pastor Casey Barton. So they start the coffee by saying, “Can we just agree that we are brothers and sisters in Christ and that we love each other,” says Barton.

“And at the end, we say we love each other again,” he says.

Two hot button issues these days are immigration and diversity. About sixty kids come to youth group on Wednesday nights. Most are Latino and some are from families who don’t come to the church. Some have family members who are undocumented. When the church was in the process of hiring a new youth pastor, one of the interview questions was, “How would you minister to a family who was in danger of being deported?”

“Fears about deportation and family disruption are real here,” says Dan Johnson, the church’s associate pastor.

Because so many church members have been farmers or work in the agricultural world, they recognize the vital role immigrants play in the American economy. Besides, at heart they are kind people, who want to love their neighbors, says Barton.

“If a member of our church was deported, our church would be horrified,” he says. “And they would want to do everything they possibly could to help them and their families.”

The church is also taking small steps to build closer relationships between ethnic groups, starting with the youth group. For years Johnson has led small groups for high schoolers, and he currently has two groups. One is white, the other Hispanic. That wasn’t planned, says Johnson—the two groups ended up that way because of schedules.

“I wish it was different,” he says.

This fall, he plans to change things. Each group originally started with six students. Now between graduations and attrition, six students remain in the two groups altogether. All of them are seniors. So now the two groups will become one. “It will be interesting to see what happens,” Johnson says.

Three years ago, Steve Hoden was diagnosed with Parkinson’s. Slowly but surely the disease has taken its toll. “One of the big things with Parkinson’s is stamina,” he says. “It takes you twice the energy to do the same amount of work you used to do without even thinking.”

The church has been very supportive of Hoden. He goes to the YMCA in Freemont, thirty miles away, for an exercise class that helps him keep up his endurance.

“The church said, take all the time you need,” he says. “That’s one of the best things about rural ministry. If you give them your hard work, they will give all the grace and time you need for whatever comes your way.”

When he was first diagnosed, Hoden says he read a short note to the congregation, telling them that he’d keep serving as long as he was able.

For a couple of years, ministry went on like it had before—with a one exception. Hoden gave up mowing the lawn, which he loved to do. He just didn’t feel safe on the mower anymore. He also stopped talking on the phone while he drives. Multitasking and Parkinson’s don’t mix, he says.

Hoden and church members kept working on mission projects, which have always been important to him and to the church. Every student in his confirmation classes receives a copy of the Covenant’s missionary prayer calendar, as does every family in the congregation. The women’s ministry contributes to Lycée Vanette, a school for girls in Congo. And Hoden tries to host Covenant missionaries as often as he can.

So sponsoring a clinic in Congo through the Paul Carlson Partnership seemed the right thing to do. But it was a challenge for a small church. The church wondered if they could come up with the funds—$10,000 a year for five years. But Hoden had faith. He found two other Covenant churches to partner with them, and it’s been a great success, he says.

Church members have also gone to Nome, Alaska, to volunteer at KICY, the Covenant radio station. They’ve hosted the station manager for fundraising dinners. Last year, six folks went up to KICY on their own. Hoden says they just called him up and told him they were going.

“I love it when things like that happen,” he says.

He’s especially proud of the church’s Sunday school offerings. The church took a shoebox and “bedazzled it,” he says. The kids collect the offering with it, and whatever comes in is given away.

“In 2016 we gave away more than $13,000 from that shoebox,” he says.

It’s things like that Hoden will miss. He has decided the time has come to retire. He’ll especially miss teaching confirmation. He’s known the students in the upcoming class their whole lives, and he’d been looking forward to teaching them. But he can’t. And he’s at peace with the decision to retire. It’s the right thing to do, and the right time.

He’s grateful for all the time he spent as a small church pastor. There’s no place else he’d rather have been.

And he hopes the next pastor will find as much joy in the work as he has. “In a small church, you can know every member,” he says. “You can know their kids. You can know their parents. There is something beautiful about that.”