[vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_column_text] [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

The Color of Law

A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America

Richard Rothstein Liveright, 368 pages

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

Reviewed by David Swanson | November 20, 2017

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

A new $23 million bicycle bridge is being built in our church’s neighborhood of Bronzeville in Chicago two blocks from an elementary school. The bridge will be beautiful, and when it is completed cyclists will cruise past the school on their way to the bike path. Maybe some of them will notice the crumbling entryway to the elementary school and wonder how our city can find money for a pedestrian bridge while our schools are asked to do more with less. Maybe they’ll notice the empty lots where public housing high-rises used to stand or the low-rise mixed income developments that are slowly replacing them. Maybe they’ll wonder why this neighborhood is mostly African American and why the neighborhood to the west has historically been white.

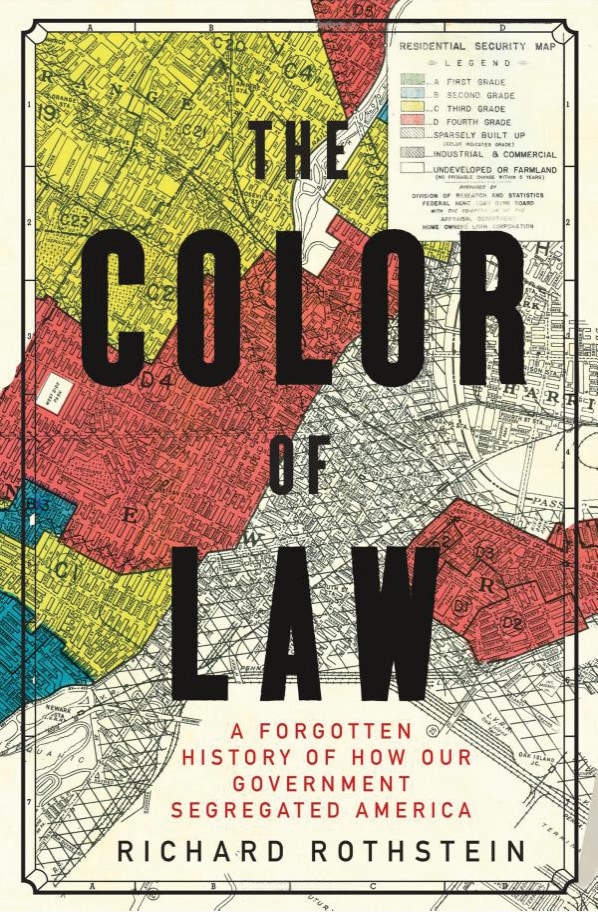

Richard Rothstein asks these kinds of questions in his meticulously researched and well-written book, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. A research associate at the Economic Policy Institute, Rothstein points out that most Americans tend to talk about segregation as being de facto, something that simply happened as the result of individual choices and preferences. Important decisions by the Supreme Court have shared these assumptions and have thus been reticent to address the destructive implications of segregation in our nation’s neighborhoods and schools. But Rothstein convincingly demonstrates that segregation in America has never been de facto; the segregation that the cyclist pedaling through our neighborhood observes is in fact de jure, a social reality constructed by our laws and public policies.

Through the middle of the twentieth century racial discrimination was federal policy. African Americans were unable to apply for federally insured mortgages, and the Federal Housing Administration would not insure any housing development that planned to admit black families. These policies extended to the first public housing developments which were first constructed for working-class European immigrants. As the need for black labor increased in northern cities, the demand for housing grew and these developments slowly opened to black residents, but they remained segregated. As European immigrants made their way in white America, they were able to move out of the housing developments, leaving behind racially concentrated pockets of poverty which were then exacerbated by new federal policies that capped the income level of the residents while simultaneously underfunding them.

As white families made their way to the suburbs—to developments funded by federal grants and made achievable by federally insured mortgages—African American neighborhoods were subject to external threats that made those same neighborhoods less desirable and unsafe. Rothstein writes that throughout the twentieth century “commercial waste treatment facilities or uncontrolled waste dumps were more likely to be found near African American than white residential areas.” He references a study that found that “race was so strong a statistical predictor of where hazardous waste facilities could be found that there was only a one in 10,000 chance of the racial distribution of such sites occurring randomly.”

The negative health impacts of living near these facilities has been extensively documented. In our city, residents in such neighborhoods are trained to intervene in the case of asthma attacks, due to the high frequency of such attacks and the distance to medical treatment.

I’ve only scratched the surface of the devastating case Rothstein makes for de jure segregation throughout American history. The Color of Law is compelling not only for the author’s precise way of telling this generally unacknowledged story, but also for the personal narratives he weaves throughout. The impact of politicians and policies is unmistakable as we encounter individuals and families whose lives were made undeniably more difficult and sometimes more dangerous by the accepted law of the land.

But the consequences were more than individual. By some accounts the average African American today holds just 6 percent of the wealth of the average white American, an ugly fact Rothstein attributes in large part to housing segregation. Statistically, black families pay more in rent, have had to commute farther for work, and, perhaps most significantly, have not had access to the equity that many white families accessed when purchasing FHA approved homes generations ago. The generational accumulation of housing injustice is not a distant memory; banks in our city have been found liable for targeting black and Latino communities for risky mortgages in the lead-up to the recent recession.

The implications of Rothstein’s book for our churches are endless. Understanding why our suburbs and cities look the way they do ought to shift how we think about their residents. When we see the intentional forces that have shaped our living environments we can be more aware of how those same often-malevolent forces are at work shaping us. From my vantage point, in a city with countless examples of segregation and its devastating implications, the most important implication is about how we pursue justice.

The Color of Law makes unmistakably clear that segregation did not inevitably happen; rather, it was chosen by those in power and embraced by the majority of white America as the best way to live. This means that when those of us who are white seek to engage the injustices wrought by segregation, we must do so from a repentant and humble starting point. We are, after all, complicit beneficiaries in the injustices we now confront.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row el_class=”cc-author-bio”][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_column_text] [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

About the Author

[/vc_column_text][vc_separator color=”black” style=”dotted”][vc_column_text]

David Swanson is pastor of New Community Covenant Church in the Bronzeville neighborhood of Chicago.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]