An Advent Journey of Separation and Loss, and The Promise of A Shared Reliance on God’s Natal Presence

For many, the season of Advent represents a journey that culminates in the joyful celebration of Jesus’s birth, full of spiritual meaning and significance but also bolstered by the excitement of impending family gatherings, the promise of gifts given and received, and the idealistic hope of peace on earth for at least one day of the year.

I certainly enjoy and revel in all the blessings of the season and strive to create a sense of joyful expectation in my own family as we draw nearer to Christmas. But at the same time, I can never forget that the beginning of Advent coincides with one of the most sobering days in my family history.

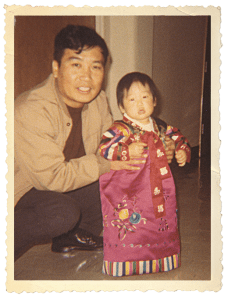

On December 4, 1950, my then thirteen-year-old father departed his hometown of Pyongyang in North Korea, along with his older brother and my grandfather. North Korea represents more than a news bullet for me; in my family the conflict that created the divided peninsula we witness today had deeply personal ramifications, as it does for countless other families who reside in the United States today.

At that time, the Korean War had been active for six months and had created a refugee crisis as thousands of Koreans who lived in the north sought to escape conscription in the North Korean army or death as a result of the military actions of South Korea, which was heavily aided by the United States. Before his departure, my dad said goodbye to his mother, who had decided to stay behind to wait for her brother, believing that they would be separated for a week or two at most. But her opportunity to leave never came as the war raged on and eventually took the form of the demilitarized zone that was erected and still exists today between the two Koreas.

After a fifteen-day journey on foot from Pyongyang to Seoul, during which my dad, his brother, and his father traversed the treacherous and freezing Daedong River and witnessed multiple civilians and livestock killed by machine-gun fire from U.S. forces flying overhead, they found a way to make a new life in South Korea. Years later my dad would make yet another challenging journey, this time by himself to the United States for graduate school with just $100 in his pocket. As December is also when we celebrate my dad’s birthday, five days before Christmas, the season of Advent for me is always coupled with a remembrance of both my dad’s harrowing departure from North Korea as well as his struggle as a foreigner in the unfamiliar lands of South Korea and the United States, where he settled permanently.

Why do we so often excise struggle and suffering from our retelling of the Christmas story? We gloss over the difficult reality of Joseph, Mary, and Jesus’s own dangerous, middle-of-the-night flight from Bethlehem to Egypt, likely hundreds of miles long involving multiple locales over the years in which they were themselves foreigners in a foreign land. Have we so idealized and sanitized the Christmas story that we cannot embrace that suffering was very likely a mainstay of Jesus and his earthly parents in their earliest years as a family? We also skim past the verse in Luke 2:35, that a sword will pierce Mary’s soul. When I think of that verse, the grandmother I never met comes to mind. How soul-piercing it must have been for her not to know what had become of her husband and her sons after their separation in December 1950.

Why do we so often excise struggle and suffering from our retelling of the Christmas story?

As a mother of three sons of my own, I wince whenever they experience their own aches, big and small, and I wish I could take any and all of their pains away, minuscule though they seem in comparison with the kinds of life-threatening circumstances that my dad experienced in his formative years. How did Mary weather the knowledge that suffering was inevitable and at her doorstep, and that it would likely involve her son’s pain and torment? These kinds of thoughts are almost too much to bear when I consider them.

And yet consider them we must, because we know from Scripture that the road of suffering leads to perseverance, character, and ultimately, hope. The Korean word han incorporates the idea of acute corporate suffering, a unique shared pain borne of being a people who have been mistreated unjustly at the hands of greater powers and principalities beyond themselves. Han has no easy English translation, but all Koreans understand this particular brand of suffering; it is uniquely ours, whether we experienced it directly through surviving the Korean War, or whether we have suffered it through the retellings of our parents and grandparents.

In the summer of 1989, I returned home from college to manage my mom’s convenience store-cafe in Washington, DC, while she and my dad were traveling to Seoul, South Korea. One day the phone rang, and one of my father’s longtime friends was on the other end. “Helen? Where is your dad?” he asked with urgency.

This friend had somehow discovered that my grandmother was still alive in North Korea, nearly forty years after she and my dad had been separated. Upon my dad’s arrival back to the U.S., he made plans to return to Korea as soon as he could, this time with a visa to visit the country he had not seen or stepped foot in since he was thirteen.

It was a few months before he could line up all the logistics, and when he finally arrived, eager and expectant to see his mother again, he found out that she had passed away before he could get there, stricken by a heart attack upon hearing that her two sons and husband had survived their trip south all those years earlier and were still alive.

After my dad spent some time reconnecting with relatives he had not seen in decades, he returned to the U.S. I will never forget his face when he disembarked from the airplane. This typically stoic man, who I had never seen cry, began sobbing when he saw me, my younger brother, and my mom. Within moments, we were all similarly tearful, and without speaking even a single word, we linked arms and traversed together as one unit through the halls of the airport.

After my dad spent some time reconnecting with relatives he had not seen in decades, he returned to the U.S. I will never forget his face when he disembarked from the airplane. This typically stoic man, who I had never seen cry, began sobbing when he saw me, my younger brother, and my mom. Within moments, we were all similarly tearful, and without speaking even a single word, we linked arms and traversed together as one unit through the halls of the airport.

Sometimes those who are not Korean wonder what binds Koreans together and gives them a strong sense of nationalism. I would venture to guess that this corporate sense of han is part of the answer.

Perhaps one of the reasons the church in America is experiencing such disunity is because we have lost a shared, centered identity of brokenness and suffering. We experience little actual persecution and pain from our collective faith in Christ. Many of us lack any true need in terms of food, clean water, and other basic needs. We are more than able to take care of ourselves, but our gain in independence has resulted in a lack of a corporate and shared reliance on God and a splintering of our identity. Instead, we have the luxury to squabble and disagree over a host of issues. To be sure, some of these issues are crucial to our witness as a faith community, such as standing for racial justice and against the lies of white supremacy in our nation and country. But I wonder if it would be easier to come to agreement on these kinds of issues if we were in solidarity in a posture of humility and dependence on God Almighty.

As a college student I would return home on holidays to visit my parents who were working their typical immigrant twelve-hour days. They were doing everything they could to make sure their children could get a good education and have all they needed to survive and thrive, and I knew better than to expect a decorated house and a Christmas tree resplendent with presents. My parents had no time for such holiday niceties, so it was my job to put Christmas together in a day or two. I would go into a frenzy as soon as I came home, searching for the artificial tree buried in the attic under its annual layer of dust, figuring out which lights were no longer viable and stretching out those that remained, and getting some cash from my mom to buy a smattering of gifts from everyone to everyone in our four-person family. It was harried, it was far from perfect, but in our imperfect Christmas we bonded over our shared knowledge that it was far more important to be together than to have a perfectly decorated house with a vast array of beautifully adorned presents.

It was harried, it was far from perfect, but in our imperfect Christmas we Bonded.

My hope and prayer for the church this Advent season is that we focus on what it means to be God’s family, united in a shared embrace of our humility and brokenness, aware of our dependence on God’s grace and forgiveness, and bonded in our communal understanding that it is only through the suffering of Jesus that we can call ourselves the church today. There is a joy that comes from the season of Christmas that is manufactured—and there is a joy that comes from internalizing the story of Christ’s birth in a way that is rooted in an understanding of what it means to be marginalized, traumatized, and foreigners in a land that will never truly be your own. May we more deeply wade into whatever frozen rivers stand before us, uncomfortable and risky though they may be, to pursue Christ at all costs. No matter our personal discomfort, may we find true salvation on the other side and be united as one in the ultimate witness to a world that so desperately needs to see our corporate message of hope and wholeness, by God’s grace, in the midst of suffering and brokenness.