Our global refugee crisis and what we can do about it. A conversation with Chitra Hanstad, Cindy M. Wu, and Susan Sperry.

According to the most recent statistics, more than 65 million people—close to the population of France—are forcibly displaced from their homes and communities worldwide. It’s the highest number of displaced people in recorded history. We asked two Covenanters who work and volunteer with refugee resettlement to help us understand the growing crisis and how churches and individuals can respond.

Why are so many people forced to flee their homes throughout the world? Why is the refugee crisis so pronounced today?

Chitra Hanstad: The number of displaced people globally is a reflection of the conflict in our world. When people are forced out of their homes by war and persecution, the number of refugees fleeing into neighboring countries inevitably rises. The ongoing crisis in Syria is the most visible and is the greatest source of displaced people today, with 60 percent of the population (12.5 million Syrians) forced to flee their homes.

But that is just one of the many heartbreaking conflicts forcing flight. Since late August more than 600,000 people from the Rohingya minority group in Burma have fled into Bangladesh to escape violence and the burning of their villages by the government. The Rohingyas have been denied citizenship in Burma for generations and are now living—and often dying—in squalid conditions. The crises in Syria and Burma are compounded by ongoing conflict in countries such as Afghanistan, Iraq, Congo, Eritrea, and South Sudan.

What are the risks and benefits of receiving refugees in the United States? What vetting process do they go through?

Cindy Wu: Refugees are the most strictly screened immigrant group to enter the US Screening is an extensive process that takes on average eighteen to twenty-four months. Under the guidance of the Department of State’s Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migrants, an in-country Resettlement Support Center (RSC) conducts initial interviews with the refugees. Those designated to come to the US—a decision made by the UN and not by refugees themselves—are vetted by several governmental entities: the Departments of State, Homeland Security, and Defense; the National Counterterrorism Center; and the FBI’s Terrorist Screening Center. As of 2016, Syrians began undergoing additional security screenings as well.

After a refugee is approved by the US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) and they pass a health screening, they are almost ready for departure. They must complete a cultural orientation, secure sponsorship assurances from a refugee agency in the States, and finally are referred to the International Organization for Migration (IOM) to make travel arrangements. Refugees sign a promissory note to repay their travel fees—on an interest-free loan—within forty-six months of arriving in the US Less than 1 percent of the global refugee population is ultimately approved for resettlement to the US

These facts should allay fears and clear up misconceptions surrounding the stringency of refugee admissions. Detractors of the refugee program have expressed concern that resettlement is an entry for terrorists, but it would be extremely difficult—and unlikely—for a terrorist to be resettled as a refugee.

Chitra Hanstad: Much has been made in the last year about the risks associated with resettling refugees. These risks must be taken seriously and we should ensure that we have effective screening steps in place.

Looking at the track record of the Refugee Admissions Program is a good place to start in assessing these fears. To date, more than 3 million refugees have been resettled through the program. Not one has carried out a terrorist attack on American soil that’s claimed American lives.

This success is a result of the strength of the American vetting process. Included in this process are biometric and blood tests, as well as verification of a refugee’s story to prove they qualify for refugee status according to the UNHCR. If they make it through multiple security screenings conducted by the State Department, a refugee will have an in-depth, face-to-face interview with a representative from the Department of Homeland Security. They then face medical screenings and cultural orientation prior to getting on a plane (the ticket for which they must repay, by the way). The rigor and duration of this process ensures that the most vulnerable and best-vetted refugees arrive.

While we think this program’s track record gives reason for confidence, we cannot eliminate all risk in receiving refugees, just as we can’t eliminate the risk that an American-born child might grow up to do terrible things. In the Bible, though, we see that God is less preoccupied with avoiding risk—he sent his Son to live among sinful humans and to ultimately die by brutal execution—than he is with knowing the suffering of the people he loves.

What does your particular agency do? How do they help refugees who arrive here?

Susan Sperry: World Relief is one of nine voluntary agencies who are contracted with the Department of State to resettle refugees in the US. When refugees arrive, World Relief partners with churches and many community organizations to help refugees get on their feet by providing basic needs support and helping refugees increase their English ability and pursue work. At its core, World Relief aims to help these new Americans integrate into local communities. This means relationships with residents in their new community are extremely important.

In 2017 World Relief partnered with churches to help 5,569 refugees resettle in the US. These numbers were significantly fewer than in 2016 (when World Relief resettled 8,352 refugees), due to restrictions the US placed on refugee arrivals last year. World Relief DuPage/ Aurora, resettled more than 650 refugees in our fiscal year 2016 (October–September). In the financial year 2017 we only resettled 336 refugees.

World Relief has twenty office locations around the US, and all work together through one centralized office who coordinates placement locations for refugees. Each of these office locations partners with local churches, working together to welcome and help refugees integrate into the specific contexts they find themselves. Some, including my office in the Chicago suburbs, also provide ESL and immigrant legal services to all immigrants.

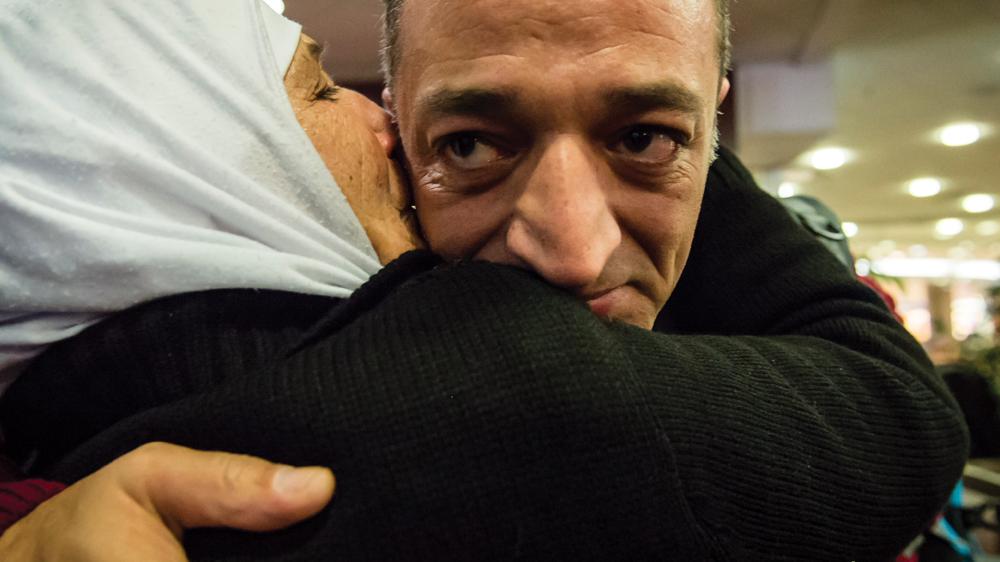

Chitra Hanstad: At World Relief Seattle, we work with refugees from the moment they arrive at the airport. We bring them back to an apartment that we’ve found and furnished for them. After this, the refugees hit the ground running. With help from our caseworkers, the children are enrolled in school and adults learn to navigate American systems like healthcare and public transit. On-site English classes help refugees develop all-important language skills, and employment specialists help refugees get their first job in America. On through the point when refugees become American citizens, we are there, helping them with challenges that arise. We do all of this in deep partnership with local churches, which are our primary source of volunteers.

For each refugee that we help resettle, the US government entrusts us with $2,125. These funds are expected to be stretched to meet a refugee’s needs throughout their first three months in the country, including paying for rent, furniture, a phone, and other basic necessities; moreover, we must pay for our costs out of this pool, including staffing and facilities. These funds are inadequate to meet refugees’ many needs, so we supplement government funding with private dollars from individuals, churches, corporations, and foundations.

What unique challenges does a refugee face—initially and then as their sojourn here continues?

Chitra Hanstad: The challenges initially facing refugees are myriad. Despite their usual excitement at the opportunity to be resettled in the US, there is the grief that comes with the permanence of their decision to leave behind their homeland.

Often, however, refugees’ emotional grief is overshadowed by practical challenges. Most immediately, they face the challenge of finding a job here. The US resettlement program prioritizes work first, whereas other countries, such as Canada, put greater focus on initially helping refugees improve English and adjust to their new country. Because of this focus on early employment, many refugees in the US face the challenge of rapidly improving their English within just months of arrival. This timetable is dictated by initial government benefits that expire three to six months after refugees’ arrival. And compounding all of this are the day-to-day challenges that come with living in a new country: navigating a complex healthcare system, learning how to take the bus, and figuring out new foods at the grocery store, for example.

Refugees often say that their second year in the US is more difficult than their first. In the first months after arrival, their focus is on the immediate tasks of acclimating themselves to their surroundings, learning English, and finding work. As they settle in, their initial excitement and stress give way to a realistic view of their situation. For many, the long road to regaining the social status they had in their home country sinks in. For others, the ongoing conflict in their homeland and the suffering of loved ones leaves them feeling powerless.

By the time they’ve been in the States for five years, refugees have often literally become Americans since this is the point at which they can apply for citizenship. The ongoing challenge—and one of the desires we hear voiced most often by our participants—is to feel part of their community. While refugee children are quick to integrate and many refugee groups form rich ethnic communities, they long to be connected to the community at large. This lack of community is one of the most pernicious effects of the fear that many Americans have toward refugees as fear stops us from inviting refugees into our homes. It is also a situation that the church has the opportunity—and the mandate (Deuteronomy 10:19)—to remedy.

Susan Sperry: Refugees have to completely start over during their first year. In that process, relationships with people within their own language group and with Americans are vital to their success. During their first thirty to ninety days in the US, refugees receive services to assist them to stand on their feet. These include receiving social security cards, enrolling children in school and starting English classes. During the next three months, adults begin working and learn to pay bills, bank independently and become more familiar with American culture. The latter months are focused on becoming increasingly independent, building stronger English and working toward greater integration into their communities.

Similar to all immigrants throughout American history, it takes time for refugees to be fully self-sufficient. Initially refugees are assisted by World Relief or a job placement agency to find a “survival job,” usually a low-wage job that helps pay basic bills. From there, we aim to help refugees plan toward future career and financial growth. Learning English is key to long-term financial growth, and World Relief encourages all refugees to continue learning and practicing English. Community volunteers play a key role with both English practice and employment-related networking.

The UNHCR aids refugees and displaced people around the world, including children. According to UNICEF, in 2015–16, more than 300,000 children—unaccompanied or separated from their families—were registered after crossing borders alone. They often end up in refugee camps where they face possible exploitation or abuse. The US does welcome some unaccompanied children but also makes a priority of single mothers with children as part of our humanitarian resettlement program.

How do you see attitudes toward refugees changing in this country?

Chitra Hanstad: Refugee resettlement in particular has become a flashpoint of political division. The discord over the last year is unprecedented in the thirty-seven-year history of the US Refugee Admissions Program. Generally, the president makes a determination of the number of refugees admitted to the country, and Congress approves it with little fanfare or controversy. Historically, leaders on both the right and the left have been supportive of the careful, compassionate work of welcoming refugees. Under President Reagan, for example, the US welcomed 200,000 refugees, more than three times the number that arrived in 2017.

Refugees who come to the US have demonstrated an incredible resilience in their often-harrowing journeys. This resilience inspires refugees to take risks that benefit our economy. They start and maintain businesses at a rate that outstrips the general population and their children outperform their peers in school.

Cindy Wu: I think there is a tension between wanting to help the vulnerable and having fears about national security and assimilation. Opinion polls reveal that throughout our history, the American public generally has not been welcoming of refugees. The US was a relatively late signatory to the major International Refugee Convention (1951) and Protocol (1967) established by the United Nations. Government policy is consistently swayed by political ideology and public opinion, and our admission numbers reflect that. In the early years of refugee resettlement, the US received refugees mostly from Europe, especially those escaping the Holocaust or communism; with time, we have been receiving more and more refugees from the developing world, people whose appearance, religion, language, or customs are more distinct from here in the US I think that feels threatening. We also receive refugees from Muslim-majority countries where extremist terrorism is an issue—and this is a growing concern for many Americans.

In what ways can the Bible inform our thinking on this conversation?

Cindy Wu: Jesus said the two greatest commandments were to love God with all your heart, soul, and mind, and to love your neighbor as yourself (Matthew 22:36-40). The first, “love God,” is the most oft-repeated commandment in the Hebrew Scriptures. What might surprise us is that “welcome the stranger” is the second.

Welcoming the stranger is part of the Christian ethic and identity. It’s what Christians do—at least, it’s what we’re supposed to do. The Bible tells us not to mistreat or withhold justice from sojourners or foreigners (Exodus 23:9; Leviticus 19:33-34) because we were once strangers. Throughout the biblical narrative, God used sojourners to advance his plan for the nations: Abraham, Jacob, Joseph, Moses, Ruth, even Jesus. Our Lord and Savior was not just a sojourner, he was a refugee fleeing persecution (Matthew 2:13-14; 8:20)! Our identification with sojourners and refugees acknowledges that we, too, are strangers and exiles on the earth. As sojourners, we make no claim to this life or this land. Rather, we recognize that everything we have is by God’s will and by his grace. That perspective should inform the way we treat refugees, our fellow sojourners.

Chitra Hanstad: The Bible not only can inform our thinking on refugees, it demands to inform it. God speaks at length in the Bible about how we should treat foreigners. The Hebrew word ger (meaning alien, stranger, or immigrant) is used ninety-two times in the Bible, usually in the form of a command to love and accept immigrants as our own. Throughout the Old Testament, God uses Israel’s own history to contextualize how their treatment of foreigners should look: “And you are to love those who are foreigners, for you yourselves were foreigners in Egypt” (Deuteronomy 10:19).

If we’re US citizens and not Native Americans, this verse should reverberate with us. In the same way that God commands the Hebrews not to forget what it was like to be immigrants, we’re commanded to remember our own families’ stories of migration when we think about how we treat immigrants coming to America today.

Many of the heroes of the Bible have immigrant or refugee stories. Abraham was called by God to leave his homeland; David was a refugee who twice fled political persecution, first by Saul and then by Absalom; Ruth was a family-based immigrant who left her homeland to follow Naomi. Jesus himself fled as a child with Mary and Joseph to Egypt to escape persecution by Herod. Our Lord and Savior, in other words, was a Middle Eastern refugee.

What are the most effective ways individuals and churches can respond to the refugee crisis?

Cindy Wu: I would encourage Christians to put on a mindset of hospitality. We are hosting newcomers, and they need guides to learn the ways of their new land. At a basic level, we can help set up their apartment before they arrive and prepare a warm welcome. At a deeper commitment level, you could help refugees learn English, if needed, and show them around town. Invite them into your life, share meals and special days together, and most of all, be a friend! Foster a friendship of mutuality where you are both learning from one another. I think you will find you have much to learn from refugees.

Chitra Hanstad: First, Christians and the church need to familiarize ourselves with God’s heart for immigrants and refugees. We are letting our politicians tell us what to believe on this topic when the Bible already has said a lot. (See recommended reading list for further biblical responses to the refugee crisis.)

Second, churches should seek out the refugees and immigrants in our communities and invite them in. Informed by the biblical mandate to welcome the stranger, we must be compelled to move to meet the needs, both physical and spiritual, of our foreign-born neighbors. At the same time, we must open ourselves to being transformed by the unique perspectives that refugees can give us of the Bible and Jesus.

Third, churches should come alongside organizations already doing this work. There are lots of great organizations, many of them faith-based, that have been doing work with refugees for decades. Find those that are near to you and partner with them by offering your prayer, your time, and your funds. World Relief has offices throughout the United States and exists to empower the local church to serve the most vulnerable, so that’s a good place to start.

Chitra Hanstad

Chitra Hanstad is the executive director for World Relief Seattle, where she has served since January 2017. Prior to this role, she consulted for Justice Ventures International, an anti-trafficking organization, in India on strategic planning and fund development and as a philanthropic adviser for the Seattle Foundation. She attends Emerald City Bible Fellowship, a Covenant congregation in Seattle’s Rainier Valley.

Cindy Wu

Cindy Wu is a freelance writer based in Houston, Texas, where she volunteers with refugee resettlement. She recently published A Better Country: Embracing the Refugees in Our Midst. She attends Access Evangelical Covenant Church and serves on the ECC Executive Board.

Susan Sperry

Susan Sperry is the executive director for World Relief DuPage/Aurora, Illinois. She has been helping refugees resettle in the western suburbs of Chicago for the past sixteen years. She earned her master’s of science in learning and organizational change from Northwestern University, and she is passionate about the ways God uses change in organizations, churches, and individuals to bring about his good. She is also a founding member of New Community Covenant Church–Bronzeville in Chicago and loves spending time with her church community.