Stereotypes and labels often blind us to the person sitting next to us each Sunday. Here’s what six Covenanters want you to know.

In the midst of theological, cultural, political disagreements and differing worldviews, how can we love each other well as members of Christ’s body? We asked Covenanters with a variety of experiences and perspectives to help us see beyond the labels that we place on each other—sometimes without even knowing it. While their stories may not change your mind, we’re hopeful they will speak to your heart.

Jopsan Flores

School cafeteria employee who attends Rolling Hills Covenant Church in Rolling Hills Estates, California.

I have resided in the United States legally for the past four years thanks to the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program. I am thirty-four years old, and it has been more than twenty years since my family left their life behind in Puebla, Mexico. They came here pursuing a better life for us.

I will always thank my family who brought me to this country with great sacrifice. Our parents were the real dreamers. My role was to attend school, get an education, learn English, and always show respect for our parents’ way of life.

I am not an issue. I am a human. I breathe, I have views, feelings, and emotions. Day by day I work hard to overcome the hurdles I face. My lack of documents has prevented me from working better jobs and achieving a better lifestyle. I have lived with the constant fear of deportation.

We are not a problem. We are people who work with decency. We are people of good. We do not take anything from anyone, and we do not want to replace anyone.

I thank God for those who fought for DACA, which gave me the chance to get a driver’s license, a work permit, a Social Security card. It freed me from the fear of deportation even if it meant I had to renew the card every two years. Thanks to DACA, I have been able to come out of the shadows.

Yet I still feel unstable in this country built by immigrants. Every day I feel like I am navigating a ship through icebergs, not knowing what will happen. When I have to tell my two boys that my work permit is about to expire, that I will no longer be able to work legally or be able to provide for their future, I feel destroyed. I have used all my credit cards just to buy food.

“It stinks that you have to prove your worth,” my son says with tears in his eyes. He knows that like me he and his brother can never give up. We look ahead to the light at the end of the tunnel, and we wait for a nation that trusts in God to do the right thing and for equality to prevail.

Devyn Chambers Johnson

Co-pastor of Community Covenant Church in Springfield, Virginia, and founder of Four More Women in the Pulpit, an initiative to connect churches to women preachers.

I grew up the daughter of a pastor/church planter. As a young adult I longed for a job and career that would offer financial stability, something that eluded my generous, ministry-minded family of origin. I never wanted to be in ministry or marry a pastor (as generations of women in my family had done before me). Becoming a pastor wasn’t even an option on the table.

So when I began to discern a call to ministry, I fought it. I had other plans. Like Jonah I ran. I ignored the voice of God. And like Jonah I was miserable.

To this day I remember the first time I said the words out loud: “I think God wants me to be a pastor.” It was an emotional and visceral experience. When I stopped fighting what I knew to be true deep in my soul, I began sobbing uncontrollably. I had no models for this.

Thanks to my father and grandfather, I knew what being a pastor looked like for men—the good, the bad, and the ugly. But I had no idea what being a pastor could look like for me. Yet God pursued me. God insisted this was my call. When I finally admitted it, I found the peace and joy that had eluded me.

In retrospect I see God’s hand over my life—I see that he was preparing me for this. As Parker Palmer describes in Let Your Life Speak, my life revealed God’s call long before I could admit it. And I believe God made a specific path for me to enter the Evangelical Covenant Church. Months before my internal struggle began to surface, I found my way to Interbay Covenant Church in Seattle, and there I found a denomination that would invest in my seminary education and ordain me.

I have received significant affirmation over the years. Yet my journey has not been easy. I spent several difficult years searching for a call. God opened the door seven years ago and I currently serve a small but vibrant church in Springfield, Virginia, as co-pastor with my husband (making me not just a pastor but a pastor’s wife!). My congregation has embraced me and my call.

But I have been burdened by the fact that this is not the norm in the Covenant. Only 7 percent of ECC churches have a woman in a lead role. We say that women in all levels of pastoral leadership is a value of the denomination, but the numbers say something different.

Several months ago I launched a grassroots movement called Four More Women in the Pulpit. I did not intend to launch a movement, I simply wanted to challenge my brothers who regularly stand in a pulpit to make room for women—to share their power with their called and gifted sisters in ministry. And to do so not with a sense of tokenism, but with a sincere and humble posture that men can learn from and be led by called and gifted women.

Jesus calls us throughout the gospels to make room for others and to lift up the voices of the oppressed. My female colleagues are longing to serve God with the fullness of who they are. They are longing to be obedient to God’s call on their lives, calls that much like mine were not something they sought but something that found them. We are not an issue. We are pastors.

Dominique Gilliard

Director of racial righteousness and reconciliation for the Covenant and author of Rethinking Incarceration: Advocating for Justice That Restores.

I am not an issue—nor a statistic. Nevertheless, when black men constitute 6.5 percent of the population, yet represent 40.2 percent of our nation’s incarcerated population, it is hard for many to fully see me as an image bearer or as their brother in Christ. Presently, experts predict that one in three black males will be incarcerated in their lifetime.

As I minister throughout the denomination in my role as director of racial righteousness and reconciliation, I commonly encounter believers who question whether racial profiling is real. They question whether people of color are credible witnesses or if we just tend to “play the race card.” I see my brothers and sisters in Christ routinely doubt the testimonies and experiences of Christians of color. I frequently hear data on institutional bias and systemic racism categorically dismissed.

I can attest that racial profiling is real! I have been stopped, for no reason, more times than I can count. I have been called a “nigger” by a police officer. I have been accused of dealing drugs and “pimping” my seminary peers (two white females) by two white officers, as we traveled to an anti-human trafficking meeting in a stigmatized section of the city. I have been detained, frisked, searched, and humiliated by officers for absolutely no reason.

While some people may believe my stories due to our relational connection or my ministerial title, far too many consistently doubt the lived experiences of people of color, even in the face of hard data that legitimizes these testimonials. In 2010 the New York Police Department revealed that officers stopped and frisked 600,000 people annually, and that 90 percent of those frisked were African American and Latino—although less than 15 percent of these stops occurred in response to any sign of criminal activity. When black and brown people are universally criminalized, we all suffer.

And when the church fails to name, renounce, and reshape all of this through biblically based discipleship, we fail to be the ambassadors of reconciliation that Scripture summons us to be.

Paul H. Betancourt

Farmer and adjunct professor who attends Kerman Covenant Church in Kerman, California.

When the Covenant Church was formed in 1885, roughly half of the US population was rural and half was urban. If you didn’t live on a farm, you likely knew someone who did. Today less than 2 percent of the American population lives on a farm and few people have firsthand knowledge of farming.

Sheryl and I were twenty-one-year-old newlyweds when we moved up to the San Joaquin Valley. There were a few eyebrows raised at the idea of a New York City–born and San Diego–raised college kid coming to learn how to farm. But the eyebrows came down when they saw me out working in the field, unafraid to get dirty and asking questions about everything. (It also helped that Sheryl had family in the area.) One of the highest compliments I ever received came second-hand from one of my neighbors: “When Paul came here he didn’t know anything, but now he has learned it all.”

Today when I introduce myself as a farmer to city folks, they are receptive, but I can see them looking for the bib overalls and the straw hat. Fortunately, these days people are taking a fresh interest in where their food comes from, which opens doors for conversations—and they stop looking for the overalls.

I’ve been asked why I voted for Trump. Whether you like him or not, what was he known for? Making deals. Ultimately I had confidence that he would manage to broker better deals than his opponent—especially trade deals, which are hugely important to American farmers. While I believe in free trade, I have been concerned that America was getting the short end of the stick on fair trade. Now we are out of the Trans Pacific Partnership and rethinking NAFTA. As well, economic growth is up, illegal border crossings are down 75 percent, North Korea has said it will come to the negotiating table, and a new Civil Rights Division has been created in the Department of Health and Human Services to help protect healthcare providers on issues of conscience. I like the president’s first Supreme Court nominee, Neil Gorsuch. And we now have a little more of our own money back in our pockets, thanks to new tax laws.

I understand that we disagree with each other on these issues. And I understand that people do not like the president personally. But in a two-party system there is no way we are going to agree on everything. We are left with an either/or choice—which is always an imperfect option. The fact is that neither the Republican nor the Democratic party aligns with the kingdom of God—and that is where my first loyalty lies.

While we are swamped with news in an endless twenty-four-hour cycle and we have the internet at our fingertips, we rarely really know what is happening beyond our own circles. We are just too busy with our daily lives and responsibilities. It takes a significant amount of energy and curiosity to put up the periscope and see what is happening out “there,” wherever “there” is.

Yes, I have tractors, drive a pickup, and live in the country. But I believe we in the church have more in common than that which separates us. We do better when we talk with each other rather than about each other.

Eva Sullivan-Knoff

Founder and executive director of Journey Center of Chicago and Covenant minister who attends Resurrection Covenant Church in Chicago.

I have the honor of being a mom to an amazing son and daughter. I focus here on my experience with my trans daughter, Bea, who came out just over four years ago. This has been one of the most life-changing events I have ever experienced.

It’s life-changing because of the hostility and discrimination that immediately became a part of her life when she came out. So much changed. Accessing medical care, getting a job, an apartment, using public transportation, public bathrooms—all became avenues of discrimination just for being herself. Fear for her safety and well-being became interwoven into the daily realities of our lives. As a parent, there is nothing more heartbreaking than to see one’s child suffer. Our ready availability and support for Bea literally became a lifeline for her.

While this journey has been hard beyond anything I can describe, it has also evolved into something incredibly beautiful. To witness Bea’s courage moves us deeply. Her living on the outside of what is on the inside has led to her deep contentment and peace—and our own. Her sense of God being with her in it has only deepened her experience.

Bea has always been deeply spiritual. With me as her clergy mom, she grew up in the church, loving and serving God, with a special affinity for the homeless. She always attended church camps—until she couldn’t. She worshiped at church—until she couldn’t. She left the Covenant with a broken heart. My heart broke too. She has found community, but it is outside the church. What have we done?

When I was a student at North Park Theological Seminary, I remember Professor John Weborg talking about religious pain versus spiritual pain. He said religious pain was pain people experience through the church or those who represent it. Spiritual pain is pain we experience in our relationship with God through suffering and unanswered questions. The danger is when people associate religious pain with spiritual pain—when someone believes they are unloved or rejected by God because that is what the church has communicated. This is heartbreaking.

Bea’s experience with religious pain is deep. In contrast, she has known God to always be there for her. After she came out, Bea heard the God who created and loves her call her by name, “my beloved daughter.” Bea has taught us much about what it means to live with integrity. Our hearts are full of gratitude for her.

Our current congregation at Resurrection Covenant Church in Chicago has been loving, supportive, and uplifting. It’s a place for our family to breathe, heal, and be ourselves. We have been raw and real there and have been met with love and support.

We don’t usually understand what we don’t know. I encourage us all to listen deeply to one another and listen deeply to God, so that we might love one another well as God intended. Bea is not an issue.

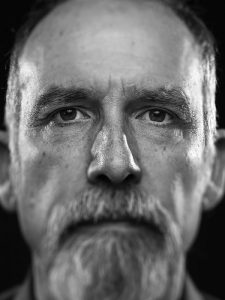

Jim Hampton

Retired police officer who attends First Covenant Church in Oakland, California.

I was born in the Philippines and came to the US in 1945 when my granddad, who was an American citizen, decided we were all going home. I was two.

My father steered me into police work—law enforcement was like a family business. He had worked in the Philippines as a type of customs officer, and his father was the chief of police for an organization that dealt with the national mining industry. Early in my career, I worked undercover in narcotics. It was the time of the flower children, and everyone was coming to San Francisco. I went on to the juvenile division and later worked in child abuse and molestation cases. That was very difficult but important—they are some of the most heinous crimes. I also worked in the intelligence bureau as an investigator inspector and later as chief of institutional police at a San Francisco hospital.

At age fifty-nine I decided I wanted to work the streets of Oakland. After a career mostly in plain clothes, I took a lateral move and started working in uniform with officers half my age. On patrol, you find out things. You develop contacts with the people who live and work in the community.

I think police officers should be evaluated on whether or not they like people. If you do, you recognize that everyone has made mistakes. You may not like what someone has done, but you don’t make it personal. That’s what I try to share with younger people on the force—don’t get to the point where you hate the job and hate the people. If you store up bitterness and cynicism, you just hurt yourself. My faith has informed the way I think about this. Jesus included everybody. There was no exclusion. He tried to make us aware of a better way.

My wife and I started attending First Covenant Church of Oakland in 1980. At that time my younger brother was a police officer in San Francisco. He was involved in a robbery in which the suspect took a woman hostage and held a gun to her head. My brother had to use his weapon and the suspect died. This was very difficult for him because police are not trained to kill. They’re trained to shoot to stop a situation. Many people told my brother what a great job he did, but he kept thinking about the guy’s mother and his family. I’ve never had a traumatic experience like that. I’ve been in shoot-outs where I shot people, but no one died.

Policing in areas where crimes are being committed can be complicated. Sometimes a community is supportive in general, but then there is a group who hate the police and teach their kids that the police are not trustworthy. When I was working in San Francisco, very young children in the street would yell, “Pigs, pigs!” to us.

Often people do not speak out against those who are committing crimes in their own area because they’re afraid. And sometimes police officers make fatal mistakes because they are scared too. When you’re fearful, you don’t assess things clearly.

I want people to understand how important both training and exposure to different parts of the community are. Police officers who don’t live in the cities where they work aren’t familiar with the community. Education and contact with residents will help members of law enforcement get to know the people and the cultures so they’re not automatically fearful every time they step into a situation.

I also want people to understand that the vast majority of police officers come in to protect and serve. That is the credo, that is the mission.