[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text] [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Columbine

Friends of Deceased Reflect on Horrific Day, Want Change

By Stan Friedman | May 22, 2018

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]LITTLETON, CO (May 22, 2018) –

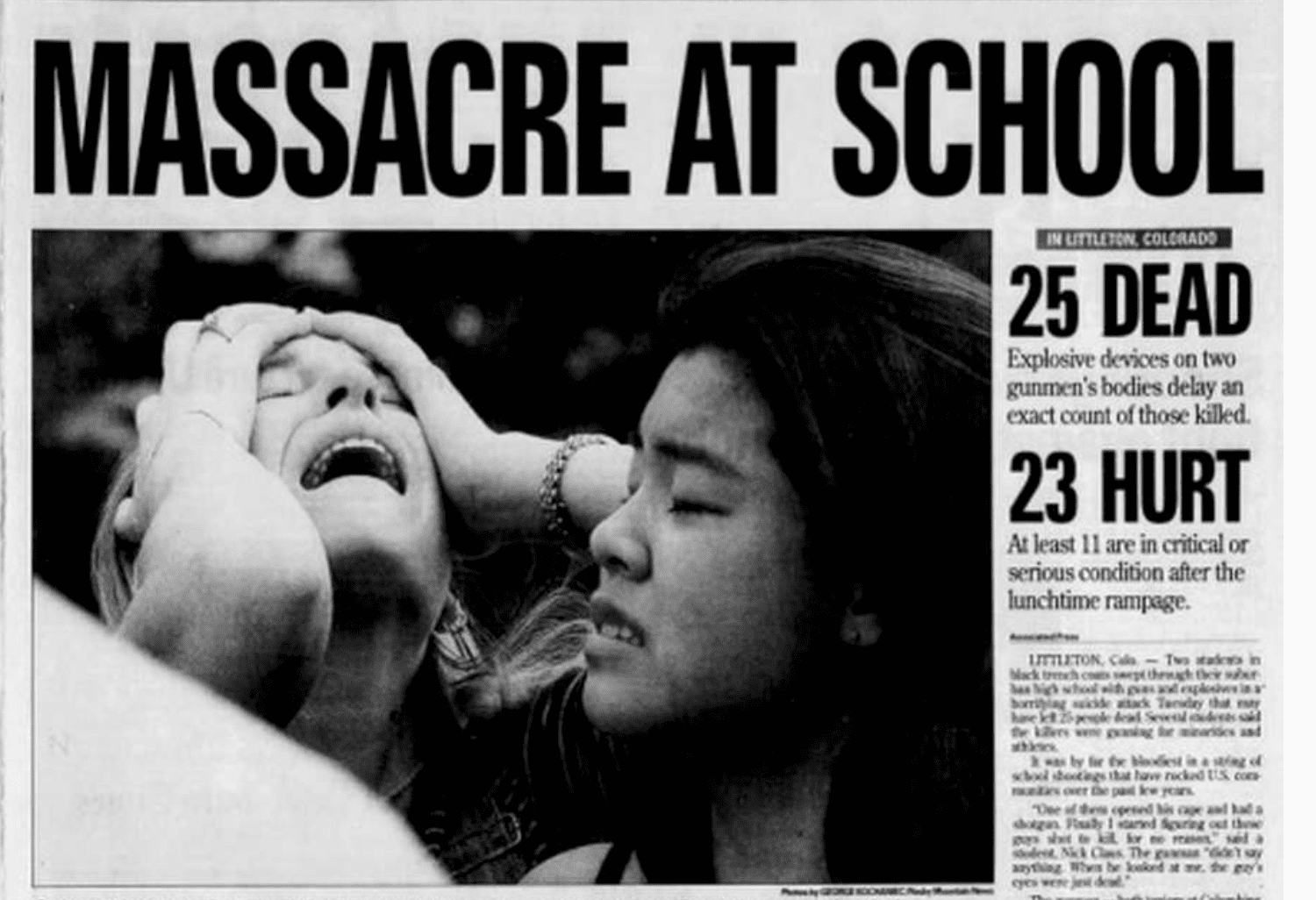

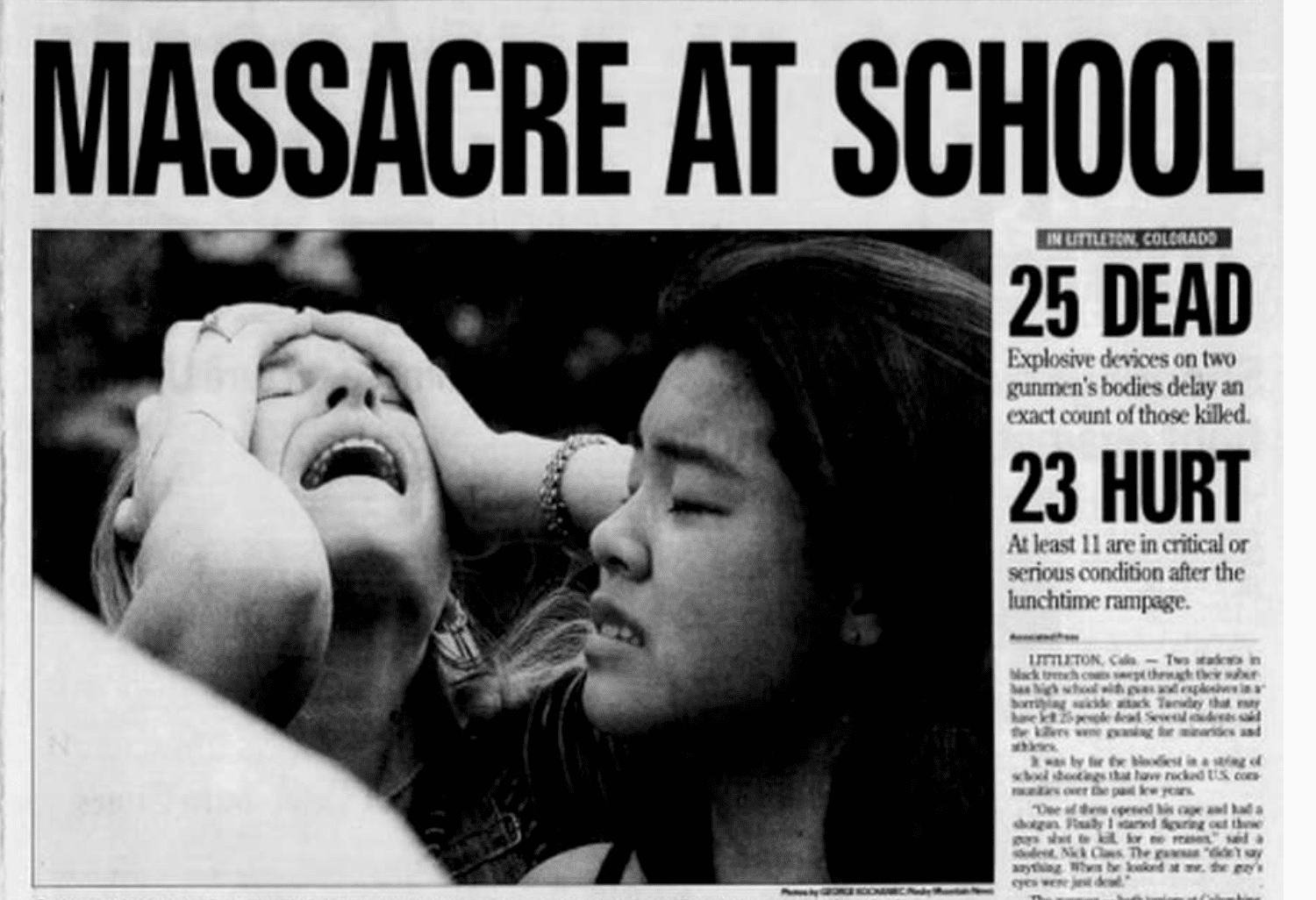

As students across the country walked out of schools last month to mark the nineteenth anniversary of the 1999 massacre in response to ongoing school violence, four Covenanters shared their experiences of the tragedy. They describe how their lives were impacted, what it was like to be the object of national attention, and what they think can be done to protect students amid a politically polarized society.

At the time of the interviews, no one doubted there would be more school shootings. Since then there have been at least three, including the shooting at Santa Fe High School, when a 17-year-old student killed eight classmates and teachers on May 18.

Amanda Meyer was a 16-year-old junior at Columbine High School when two fellow students killed her best friend, Cassie Bernall, 11 other classmates, and a teacher before killing themselves.

Lisa Holmlund was a sophomore at Seattle Pacific University when the massacre occurred. She had grown up in Littleton and was preparing to go back home for the summer to serve as a youth intern at Centennial Covenant Church, where Meyer and a number of other Columbine students attended.

Ryan Ashley was the youth pastor at the church and one of the first ministers on the scene.

Steve Thulson was the pastor at Centennial.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”2/3″][vc_single_image image=”39121″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”center”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”39105″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”center”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Every day, Meyer had lunch with her best friend, Cassie Bernall, in the school library. But that day in 1999, friends invited Meyer to go to Taco Bell during her open period. “I never left campus for lunch,” Meyer says. “I don’t know why I said yes. I don’t love Taco Bell, but I went with them.” She figured she would make it back to school in time to connect with Bernall.

But after Meyer spilled food on her clothes, her friends drove her home to change. Her dad was home, and she stopped to talk with him for several minutes. Then they drove back to the school.

“We parked the car and were walking in, but people were running out already telling us not to go in,” Meyer recalls. “Being 16-year-olds, we tried to go in anyway. But a teacher stopped us. I thought it was a big joke. Nothing like this had happened before.” They made it close enough to the entrance to hear the commotion and gunshots.

That night she and her family gathered at home with the pastors from Centennial waiting for news about Cassie. “People were holding out hope but we knew. When the coroner’s office called to ask what Cassie was wearing that day, it was confirmed that she had died.”

Lisa Holmlund was in her communications class. Two weeks earlier, she had accepted the position as full-time youth ministry intern for the summer back home in Littleton. On April 19, someone came into the class and said, “Lisa, aren’t you from Littleton? There’s been a shooting at the high school.” Then the class watched the news coverage on the TV in the room.

“I remember just looking at it in shock and going numb,” Holmlund says. “I knew I needed to do something but I wasn’t sure what. I felt like I wanted to cry, but I also wanted to be angry, and I also felt like I needed to be there.”

Her parents called to say that Holmlund’s next-door neighbor Lauren Townsend had been killed. The two weren’t close, but they used to chat in their adjoining backyards.

Holmlund wanted to come home, but was persuaded by her parents to stay and finish up the semester, which had only a couple weeks left.

These kids were trying to process trauma on a philosophical or theological level in front of a microphone. They were trying to make sense of it in the national spotlight. —Ryan Ashley, one of the first ministers on the scene

Ryan Ashley was in a staff meeting at Centennial when he heard the news. “I grew up in the YoungLife tradition, which included connecting with students on campus,” Ashley said. “Back in those days you could go to the school, bring a cheeseburger, and have lunch with students.” He knew a number of the students who were killed.

He drove to the elementary school where many of the Columbine students had been taken by bus. He spent the afternoon praying and talking with students.

Steve Thulson was in the same staff meeting with Ashley. “One moving experience I had that awful day was a phone call from Jerry Mosby, pastor at Fellowship Covenant Church in the Bronx, New York City,” Thulson says. “We barely knew each other, but he wanted to express that his church was praying for us and he prayed directly on the phone. After thanking him, I said I could imagine he’d been alongside families who’d lost children due to gun violence. He admitted, ‘I’ve buried way too many.’ It struck me then that our tragedy in suburbia, making international headlines, was all too common and unnoticed in black urban America.”

In the Following Days, the Country Watched

Two weeks later, Holmlund returned to Littleton. As the only woman on staff at the church, she says, she realized one of her roles would be to be present to Meyer. But Holmlund wasn’t sure whether she was helping. “I was so concerned as a college kid new to ministry about doing it right,” she says. “Am I doing the wrong thing? Am I going to make things worse? But some amazing women at the church reminded me often, ‘Lisa you are called and you are gifted, and you are making a difference with your presence.’”

The nation was glued to its TV sets. One of the hard parts, Ashley says, was responding to the media. “We got offers to fly to the Today show and do all these things. To be honest, that was hard. Although we wanted to tell the stories, it could really distract from the healing.”

“These kids were trying to process trauma on a philosophical or theological level in front of a microphone,” he adds. “They were trying to make sense of it in the national spotlight.”

“I was glad people cared,” Meyer says. “People showed a lot of love and support for us from all around the country.” At the same time, she says, “I wanted nothing more than for people to leave me alone, but I was 16 and I felt like I had to engage with people.”

She did talk to a number of news outlets. They especially wanted to know about Bernall, who was reported to have responded “Yes,” to the question, “Do you believe in God?” before she was shot.

“I was supposed to be with a friend who ended up dying. I wasn’t there with her—and because of that I’m alive. I know this is called survivor’s guilt. I know she would not have wanted me there. Yet I still feel guilty a little.” —Amanda Meyer

When she graduated, Meyer left Colorado to attend school in California. She hoped that relocating would help her escape the attention, but when people found out where she was from, they automatically wanted to know about the shooting.

“I remember being on a plane in college and my sister was talking with someone and started to say she was from Littleton,” Meyer recalls. “I wanted to jump on top of her and put my hand over her mouth. I learned that early on because you don’t want the questions.”

A year and a half after the event, Ashley left ministry, thinking he would never go back. “I was physically and emotionally exhausted. I had nothing left,” he says.

Meyer experienced her own PTSD. “I would be out somewhere, and I’d have this thought, ‘Oh my gosh, something could happen.’ A loud noise would throw me off. I’d really freak it out.”

But the greatest pain was thinking how she had left the school that day. “I was supposed to be with a friend who ended up dying. I wasn’t there with her—and because of that I’m alive. I knew this is called survivor’s guilt. I know she would not have wanted me there. Yet I still feel guilty a little.”

Continued Healing

Meyer is now a physician. She moved back to the area after her residencies and lives about 20 miles from Littleton. “I actually found it a relief moving back,” she says. People don’t ask as many questions.

She still keeps in touch with Holmlund, Ashley, and Thulson. “When I go back to see my parents, I go to the same church. It’s good to be in a place where you are known.”

“Every time there is another mass shooting, my heart sinks, and then it starts racing,” says Holmlund, who now serves as pastor of youth and family ministries at Grace Community Covenant Church in Olympia, Washington. “I know I don’t have PTSD the way those who actually went through the experience do, but it’s sort of like a pastor’s PTSD. Am I ready to be a person who is safe, a person who is representing the most holy God in the midst of pain and suffering? Am I able to be present and have the energy for people who need it?”

Ashley has returned to ministry. In 2011, he planted Restoration Covenant Church in Arvada, Colorado. A close friend, who also is a volunteer at the church, calls him after each school shooting.

“We can’t have a bumper sticker kind of faith. There is systemic evil. It’s not just the devil, it’s not just sin, but it’s also the systemic evil,” —pastor Steve Thulson, who waited with Meyer’s family

All four say they are impressed by the Parkland High School students and others around the country who are protesting to stop the violence.

“I’m so glad they are standing up,” Meyer says. She is frustrated that little has been done to stop such tragedies. “Are we not adult enough to put our heads to come up together with a solution?”

Solutions, however, are complicated.

“We can’t have a bumper sticker kind of faith,” Thulson cautions. He adds, “There is systemic evil. It’s not just the devil, it’s not just sin, but it’s also the systemic evil.” That presents itself in a number of ways, he says, including the lack of appropriate care for people with mental illnesses.

All four are adamant that care for people with mental illness needs to improve.

Meyer doesn’t discuss gun control with others. “They won’t talk to me about it,” she says. “I have a card to play that they don’t.” But, she adds, “It can’t be just gun laws. It has to be caring for kids, it has to be being part of a community.”

Meyer says she talks now about possible solutions when the conversations can be part of a real adult dialogue directed at stopping the violence.

“When I was 16, I did not think I was a kid, but now that I’m older, I see that I was a child. A child,” Meyer says. “I had no business dealing with those issues.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

For related story, see Can’t Tell Kids It Won’t Happen