[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row el_class=”hero-header-text”][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Stories that Shaped my Faith

When the Cup of Endurance Runs Over

by Erika Carney Haub | June 8, 2018

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

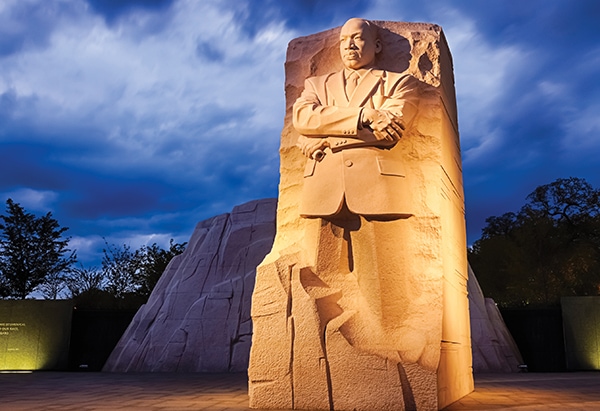

I stepped out onto the tiny porch of my sister’s second floor apartment and settled into a chair nestled among a handful of potted plants. Palm branches flanked the porch, creating a tiny urban sanctuary in the South L.A. neighborhood where she lived. It was night and the porch light lit the pages of the small paperback I had brought to read—Why We Can’t Wait, by the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Seldom has a book so captivated me—pain and beauty and hope came barreling at me full speed that night. Having spent seven years in urban Chicago working with youth, I found language for many of the fights and furies I had experienced in ministry. It also raised a deeper challenge and conviction for what it meant for me, a white woman, to push for racial justice in the church. King’s words jumped off the pages as I acknowledged my own ability to self-protect and retreat and stay silent when speaking up might cost more than I was willing to give.

I hesitate to summarize Dr. King’s text—it’s so much more than a thesis statement or a single story. Perhaps the most helpful introduction to this work is found in the opening to the famous “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” which speaks to the title of the book:

“I guess it is easy for those who have never felt the stinging darts of segregation to say ‘wait.’ But when you have seen vicious mobs lynch your mothers and fathers at will and drown your sisters and brothers at whim; when you have seen hate-filled policemen curse, kick, brutalize, and even kill your black brothers and sisters with impunity; when you see the vast majority of your twenty million Negro brothers smothering in an airtight cage of poverty in the midst of an affluent society…then you will understand why we find it difficult to wait. There comes a time when the cup of endurance runs over and men are no longer willing to be plunged into an abyss of injustice where they experience the bleakness of corroding despair. I hope, sirs, you can understand our legitimate and unavoidable impatience.”

Covenant minister, speaker, and educator Brenda Salter McNeill suggests that the road to racial reconciliation is a journey. King’s words have been for me “rod and staff” companions on this road. And his clarion call to repentance and repair remains timely today for the legacy of racism in our country and the clear and present suffering it produces—suffering that is too often met by the scandalous silence of the church. The very existence of the Twitter hashtag #WhiteChurchSilent gives evidence to the continued urgency for a book like this.

When King writes of police violence, I can only shudder considering the horror of today’s headlines and the protests that continue to erupt from justice denied:

“… armies of officials are clothed in uniform, invested with authority, armed with the instruments of violence and death, and conditioned to believe that they can intimidate, maim, or kill Negroes with the same recklessness that once motivated the slaveowner. If one doubts this conclusion, let him search the records and find how rarely in any southern state a police officer has been punished for abusing a Negro.”

After the events in Ferguson, Missouri, put our nation’s racial division on stark display, I decided to speak about police brutality from the pulpit to my mostly white congregation. I did not give statistics, nor did I seek to litigate the death of Michael Brown. I simply shared a story of one of the kids I knew in Chicago whose face was pounded into the concrete because he made the mistake of running when he saw a police car. I contrasted his story with the many I could recall of my own high-school peers where the most humiliating thing that happened at the hands of a police officer was having them drive you home to your parents.

We are not so distant from King’s description of lives lived “harried by day and haunted by night by the fact that you are a Negro, living constantly at tiptoe stance.” This book reminds me that silence is never a neutral stance.

This book reminds me that silence is never a neutral stance.

A seminary professor once told me that “a prophet is someone who knows what time it is.” For all of us who wish to enter dialogue or practice true Christian listening or move in a direction of Philippians 2 compassion when it comes to our life together as the body of Christ, Why We Can’t Wait is a must-read for its insight, prophetic urging, and truth-telling.

I don’t want to find my life and my church and my denomination so exposed in this book’s pages, but I do—and that tells me that we are still asking our brothers and sisters of color to be measured, to practice moderation, to wait. And to that, Dr. King’s words rise from the pages: “We need a powerful sense of determination to banish the ugly blemish of racism scarring the image of America. We can, of course, try to temporize, negotiate small, inadequate changes and prolong the timetable of freedom in the hope that the narcotics of delay will dull the pain of progress. We can try, but we shall certainly fail. The shape of the world will not permit us the luxury of gradualism and procrastination. Not only is it immoral, it will not work.”

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row el_class=”cc-author-bio”][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

About the Author

[/vc_column_text][vc_separator color=”black” style=”dotted”][vc_column_text]

Erika Carney Haub is the associate pastor of Shoreline (Washington) Covenant Church, where she serves alongside her husband and four children. Having grown up at Shoreline Covenant, Erika finds particular joy in raising her own kids in the same church family that taught her to walk with Jesus. When she is not busy at church and serving in the community, she can be found on any number of soccer pitches, baseball diamonds, auditoriums, and performance venues. Erika enjoys poetry, live music, and posting pictures of her boxer puppy on Instagram.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]