Stories that Shaped my Faith

A Shadow of Hope

by Alicia Vela | January 21, 2019

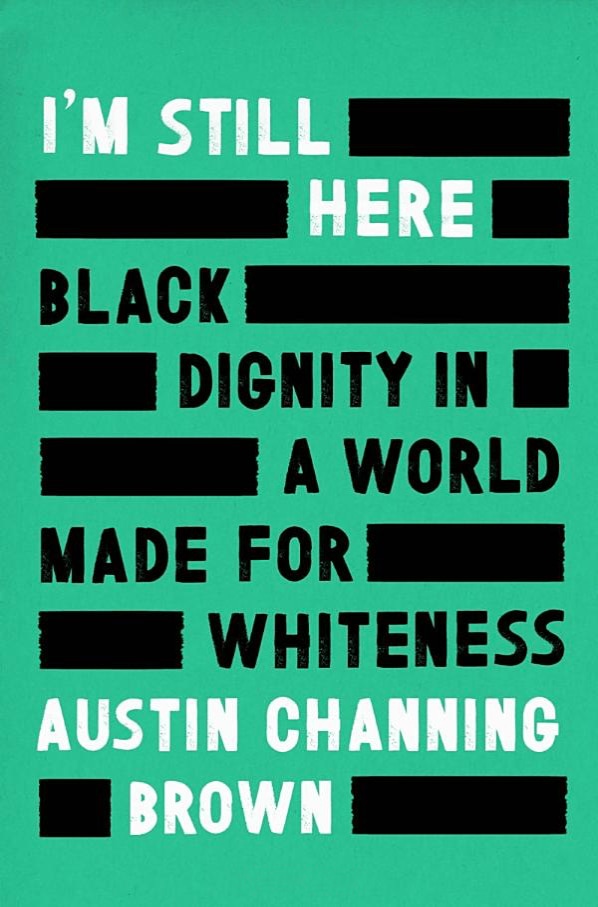

Whenever I hear Austin Channing Brown interviewed about her book I’m Still Here: Black Dignity in a World Made for Whiteness, one of the first questions she is asked refers to the opening line of her book: “White people can be exhausting.” It’s more than just a provocative first line—it sets the tone of the book. It’s a signal to readers that Brown is not going to dance around the truth in this space.

Whenever I hear Austin Channing Brown interviewed about her book I’m Still Here: Black Dignity in a World Made for Whiteness, one of the first questions she is asked refers to the opening line of her book: “White people can be exhausting.” It’s more than just a provocative first line—it sets the tone of the book. It’s a signal to readers that Brown is not going to dance around the truth in this space.

It’s also a signal to all of us who know the deep truth of that sentence. Brown’s book came to me when I was in a season of exhaustion and desperation. I had been wrestling with my own voice and identity in the conversation of whiteness and the minority experience. I had been labeled “divisive, negative, toxic,” just as Brown has.

And I realized that I had developed a habit of giving in and shying away from debate because I can “pass” as white—and I was horrified. I needed some sort of revitalization in this journey toward reconciliation. I came to I’m Still Here with a hope that I would find some inspiration or a way forward. When I read that first sentence, I breathed a deep sigh of relief.

The pages that follow are a deep dive into the reality of being a black woman. Brown challenges white fragility and reframes what reconciliation could look like in our churches and workplaces. She’s vulnerable in sharing her experience with whiteness and how it has affected her. She recalls her own version of “the talk” that many minorities have experienced—the lessons handed down by parents to their children on how to interact with the white world around them. She shares the ups and downs of trying to find her space within both the black and white communities she has been part of throughout her life.

Even when it feels like hope has died,

a shadow of it remains.

Brown also writes about the ups and downs of being one of the only black women in organizations that say they strive to be a safe place but in practice do more harm than they know. She shares her experiences of encountering white privilege and how she learned to respond in those spaces of her life and career.

These stories weren’t shocking to me; rather, they were tender and real. As a biracial woman who has navigated primarily white (and male) spaces most of my life, I saw myself in her pages. Brown drew me into her experience. While my friends read alongside of me, expressing shock and disgust at the behaviors she describes, I simply nodded. I underlined passages, not because they challenged me but because I saw myself in them. She spoke of raising uncomfortable incidents in her workplace and how the reaction was often to placate her or to challenge her to think better of the white people she interacted with. I resonate so deeply with the hope that just once someone would name the racism or white supremacy rather than calling it a “misunderstanding.”

I’m Still Here is a reminder to all of us that we live in a culture that expects black women to cut part of themselves off in order to survive in the dominant culture. Time and time again we place limits on people of color, expecting them to amend their actions, their words, and their appearance in order to fit in. Too often, even in the church, we don’t want to admit that for centuries we have continued the legacy of white supremacy. Too often we act as if it’s enough to say we’ve moved on and we’re better than that now. But as Brown points out, “Racism never went away, it just evolved.”

And yet Brown finds a way to find “a shadow of hope.” She reflects on the weariness of working toward reconciliation. But even when it feels like hope has died, a shadow of it remains. It’s “knowing that we may never see the realization of our dreams, and yet still showing up.” This is the call for those of us who want to see a change, a way forward out of our racist history. It’s a call to continue to show up, even when it feels like a constant uphill climb.

As I read this book, I realized that what Brown was showing me how to do was steward my story well. The experiences she shared, the stories she told are incredibly vulnerable. All these instances of being marginalized, talked down to, and treated as if her voice didn’t matter shaped her into the woman she is today. Her story is one of grit and resilience. She does not owe us an explanation of what it’s like to be her, but she chooses to share her story in order to call attention to how whiteness has stripped dignity from people of color.

Through her story, through her challenge to find a new sense of hope in a time that too often feels hopeless, I realize that my own story is no accident. I see God’s handiwork on creating me in this body, with these experiences because of this body. How I choose to steward my story from the biracial female perspective is vital. If Austin Channing Brown is standing up to say that she’s still here, I’m standing alongside her, demanding that we call attention to the things many are afraid to see in our communities.

About the Author

Alicia Vela is pastor of youth and young adults at Roseville (Minnesota) Covenant Church. She’s a two on the Enneagram, which basically means she loves nothing more than sitting across the table from someone, drinking coffee and telling stories.