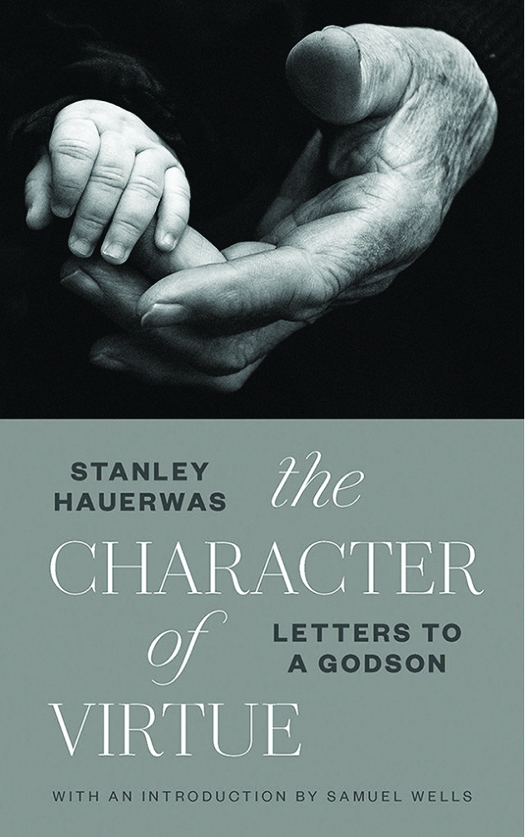

The Character of Virtue

Letters to a Godson

Stanley Hauerwas

Eerdmans, 205 pages

Reviewed by Don Johnson | February 6, 2019

Grandparenthood overwhelmed me and took my heart hostage. From November 2016 until August 2018 I had the unique privilege of spending every Friday night through Saturday afternoon with an alternating set of grandchildren (there are two sets). During that time, I was able to observe the wonder and mystery of their development—from lying on the ground to rolling to crawling to standing and walking. I watched their language form and vocabularies expand. I prayed with them over meals and at bedtime. And I would snuggle with them Saturday mornings while their parents got some much-needed extra sleep. Because their parents invited me in, I was an honored guest observing emerging personalities.

I confess that I am a much better grandparent than parent. When my children were young, I was so busy at the church and at home there was always a list of things that needed to get done. I felt like I was pushing kids through tasks and cleaning up messes. Not so as a grandparent. I make messes with them. When we return from the beach or park, we are always messier than when we left.

So it is with the eyes and heart of a grandfather that I read Stanley Hauerwas’s book The Character of Virtue: Letters to a Godson. The compelling beginning is from the author’s friend Samuel Wells who asked Hauerwas not only to be the godparent of his son Laurie but also to write his son one letter per year on a Christian virtue. Hauerwas is an American from Texas who is writing to Laurie, who is English. Every chapter begins with the anniversary date of Laurie’s baptism and the year. The book is composed of fourteen chapters on virtues: kindness, truthfulness, friendship, patience, hope, justice, courage, joy, simplicity, constancy, humility (and humor), temperance, generosity, and faith. The closing chapter, a reflection on the nature of character, is written with the knowledge that these letters were becoming a book.

The chapters are a personal, intimate, and vulnerably honest conversation from an older man to a child he hopes to know. As he writes, Hauerwas proposes that every virtue has a vice to either extreme of it—the virtue lies in between. The virtue of kindness can slide into the vice of sentimentality. Truthfulness can be compromised into lying, friendship can devolve into shallowness—Hauerwas writes, “Americans are friendly, but we aren’t good at being friends.” Hope can slide into either optimism or cynicism.

Often the chapters are a devotional reflection on New Testament texts that make a theological argument for these virtues being foundational to the life of a disciple. One cannot read The Character of Virtue without being aware of Hauerwas writing to Americans who see truth, virtue, and character under assault from the highest levels. While not going political, Hauerwas calls for courage and bravery to speak the truth regardless of personal cost. I could not help but reflect personally that in my pastoral desire to remain politically neutral (a longstanding Covenant position), I wonder if I have not compromised on some virtues so that I could remain professionally safe.

This book would be a powerful tool for a small group to read together and discuss. While the first letter was written in 2002 and the last one in 2017, this book is as timely as any could be for us today.