Seeking Safety

The painful passage of a family fleeing persecution and the power of Covenant voices

by Stan Friedman | March 15, 2019

In December 2017, a man on a motorcycle pulled up in front of Adriel Tirado’s home in Upata, Venezuela. A young girl and her mother were outside. He shot them, killing them both.

That’s when Adriel knew his family had to flee. A pro-government gang terrorizing the country had mistaken the two victims for his wife, Sofia, and one of his daughters, he says.

It was not the first time their lives had been threatened. Adriel, a pastor and attorney, had been a long-time critic of the government. Much of his legal work entailed prosecuting officials under Hugo Chávez’s regime.

Seven years earlier, Adriel had loaned his car to his brother. Hours later, gunmen pulled up to the car and fired inside, killing Adriel’s brother and a cousin. Shaken but uncowed, Adriel vowed to continue prosecuting corruption in high places, and fighting for the rights of all citizens.

“I felt I had to do it in memory of my brother,” he says.

Two years later, when Sofia and their daughter were visiting his mother-in-law, gang members burst into the house, demanding to know Adiel’s location. He and his father-in-law, a leader in the opposition party, had gone out of the state.

The gang beat the women, ripping out their hair.

“They were humiliated while being cruelly terrified to beg for their lives and that of our infant daughter,” Adriel says.

After that, he moved the family elsewhere in the country but continued to speak out as a member of the country’s largest opposition party, Acción Democrática.

Other subsequent assassination attempts occurred over the years, but the killing of two innocent people convinced Adriel his family needed to leave Venezuela.

“That was the trigger,” he says. “As a father, I couldn’t bear the possibility that something would happen to any of my daughters or my wife. That’s why I stopped the fight against the government and decided to abandon my ideals, after more than 16 years of trying to seek changes through democratic and legal means.”

So on January 13, 2018, Adriel, Sofia, and their two daughters, ages six and two, flew to Caracas, the Venezuelan capital. Several days later, they headed to the Mexican border city of Tijuana. Their intent was to cross the U.S.–Mexico border into San Diego and present themselves to the U.S. Customs and Border Patrol, requesting asylum.

Abraham Bejarano, pastor of Emmanuel Covenant Church in the Los Angeles suburb of Northridge, had planned to pick them up. Abraham is originally from Venezuela, and the two pastors knew each other from doing ministry there. Before Adriel and his family arrived in the U.S., Abraham had spoken to his friend on the phone. “I told him, ‘I trust the system,’” Abraham says. “‘Don’t worry, you are in a safe place.’”

He was wrong.

At the border, Adriel was separated from his family and detained. Sofia and their daughters also were held. Adriel says he never imagined he would be separated from his family, let alone incarcerated, especially since he had sought legal entry into the United States.

“I presented myself for asylum,” he says. “I told them I was coming from Venezuela. The situation in Venezuela is known to everyone in the world.”

Asylum seekers must show a “credible threat” to their safety in their initial interview and they have a year to complete their application paperwork.

Ever since the death of Chávez in 2013 and the presidential takeover of his handpicked successor, Nicholas Maduro, Venezuela has been in an economic freefall. Inflation in 2018 was more than 1 million percent. According to the United Nations, three million people—10 percent of the country’s population—have fled Venezuela since Maduro took power due to the economic crisis and violence against the opposition. International organizations have likened the refugee crisis to Syria’s.

Maduro was elected last May in elections widely considered to be fraudulent. Juan Guaidó, the head of the opposition-controlled National Assembly declared himself the interim president under the country’s constitution, a claim recognized by more than 20 countries, including the United States and other Central and South American nations. The government has enacted violent crackdowns against protestors and opposition party members.

Making his claim for asylum, Adriel showed agents his documents, which included news stories about how he had prosecuted Venezuelan officials for “atrocities” and been denounced by the government. Officials asked the family to move into another area.

“They immediately took my belt and my shoes,” he says. “They pushed me, my wife, and my kids against the wall and treated us like criminals.”

His family screamed and cried as he was led away. He found out later that Sofia and their daughters slept on the floor that night. The next day, an officer had mercy on Adriel, telling him, “You need to see your daughters and say goodbye because you are going to spend a long, long time away from them.”

The officer was right. It would be ten months before Adriel saw his family again.

Over the next 20 days, he was transferred from one facility to another via long bus trips and flights, during which he was shackled at the wrists, arms, legs, and waist. He eventually wound up in the Folkston ICE Processing Center thousands of miles away in Georgia.

The 800-bed facility is owned by GEO Group, one of the largest owners of private prisons in the U.S. The processing center is adjacent to D. Ray James Facility, a prison also owned by GEO.

While Adriel was being moved around the country, Abraham, the Los Angeles-based pastor, hired a lawyer in California. Together, they procured the release of Sofia and their daughters, who had spent ten days in a local detention facility. Once they were free, they moved in with Abraham and his wife.

While Adriel was being moved around the country, Abraham, the Los Angeles-based pastor, hired a lawyer in California. Together, they procured the release of Sofia and their daughters, who had spent ten days in a local detention facility. Once they were free, they moved in with Abraham and his wife.

But they had no information about Adriel—no idea where he was and no way to communicate with him. Abraham called various officials, seeking information, but he says no one would give him an answer.

It would be several days before Adriel was fully processed at Folkston and allowed to make one phone call. He called Abraham. “That was the first time we knew where he was,” Abraham says.

Abraham then hired attorneys in Georgia. Even though Adriel legally had the right to consult with counsel, he was prevented from meeting with his attorneys.

“ICE told him that asylum seekers can only have access to legal counsel if they have a family member legally in the United States,” Abraham says. “I’m a friend, a colleague in the ministry, so I applied to be his sponsor, but they wouldn’t accept my sponsorship.”

The treatment of detainees at the center was cruel, Adriel says. His description of the conditions mirrors complaints filed in cases around the country, including the two other detention facilities in Georgia. He says he slept in a room with 63 other men. Meals were meager and sporadic.

Adriel worked on a field crew cutting grass. He says the drinking water came from corroded tanks and often came out of the faucet brown.

During extended cell searches, which occurred every three hours and took hours to complete, prisoners had to remain in their beds. Lights remained on throughout the night.

The men who were approved to work in the detention center earned $1 for every four hours of labor. In addition to the field work, other crews cleaned offices or cooked meals for staff. Many of the incarcerated men used the money they made to buy food they could cook in a microwave.

“Sometimes you would wait in line for hours to put your food in a microwave,” Adriel says.

Project South, an advocacy group, released a report in May 2017 on the two other detention facilities in Georgia. “The unhygienic environment and poor living conditions not only take a toll on the detained immigrants’ health, but also have a negative and disturbing impact on the minds of the individuals being held in detention,” according to the report. “Detained immigrants are not provided with adequate access to legal information, and phone usage is both limited and expensive.”

In February, Azadeh Shahshahani, the group’s legal and advocacy director, wrote in an email that “conditions at the privately operated detention centers in Georgia, the Stewart Detention Center and the Irwin County Detention Center, are horrendous.” She added: “We have also documented racial slurs and verbal abuse by the guards, inedible food, foreign objects found in the food, and unsanitary conditions.”

Following the suicide of a detainee at a GEO-operated center near Los Angeles, the Homeland Security Office of the Inspector General found significant health and safety concerns in the facility, including improper and overly restrictive segregation, inadequate medical care, and nooses made of bedsheets in detainee cells.

“This happens all the time,” says Tim Campbell, an attorney for Adriel. “That’s the way they do things.”

ICE says it does not comment on individual cases and denies detainees are mistreated.

I told him, ‘Don’t worry, you are in a safe place.’

That was wrong.

Adriel’s physical and emotional health deteriorated. He also struggled to hold onto his faith. “Often,” he says, “I felt abandoned by God.”

He says ICE workers told him that no one was going to help him.

“I thought I would never see my family again,” he says. “I thought they were going to deport me back to my country, and I was going to die. I would never know where my daughters were.”

In fact, Abraham and others were working on his behalf. Abraham mailed packages of materials that were required to support Adriel’s asylum claims.

“They would send them back unopened, saying I was missing files,” he says. “The files were in the package, but they never opened it. Each time I sent an application, the fee was $300. It was just money-making.”

Abraham visited Washington to discuss Adriel’s case with Georgia’s senators, David Perdue and Johnny Isakson, as well as the representative of the First Congressional District, Buddy Carter.

Covenanters around the country responded, changing Adriel’s future.

In June, The Covenant Companion published an online column by Abraham asking people to send letters in support of Adriel to his lawyer. Covenanters around the country, as well as other readers, responded, changing Adriel’s future.

“Thousands and thousands of letters requesting his freedom were sent. They were presented to the senators and congressman,” Abraham says. “The next time I had a meeting with lawmakers, they asked me to come inside, and they said they had requested his release from jail.”

Within a week of the letters being submitted, the government released Adriel.

“If it hadn’t been for the article you published, and the fact that the light shined on the darkness, we never would have been able to get Adriel out,” Abraham says.

It would be another three months before a judge would hear Adriel’s case and grant permission for him to be reunited with his family in California. In the meantime, he stayed with an aunt whom his lawyers had discovered. She happened to live in Georgia.

When he was finally released back to California last September, the reunion proved bittersweet.

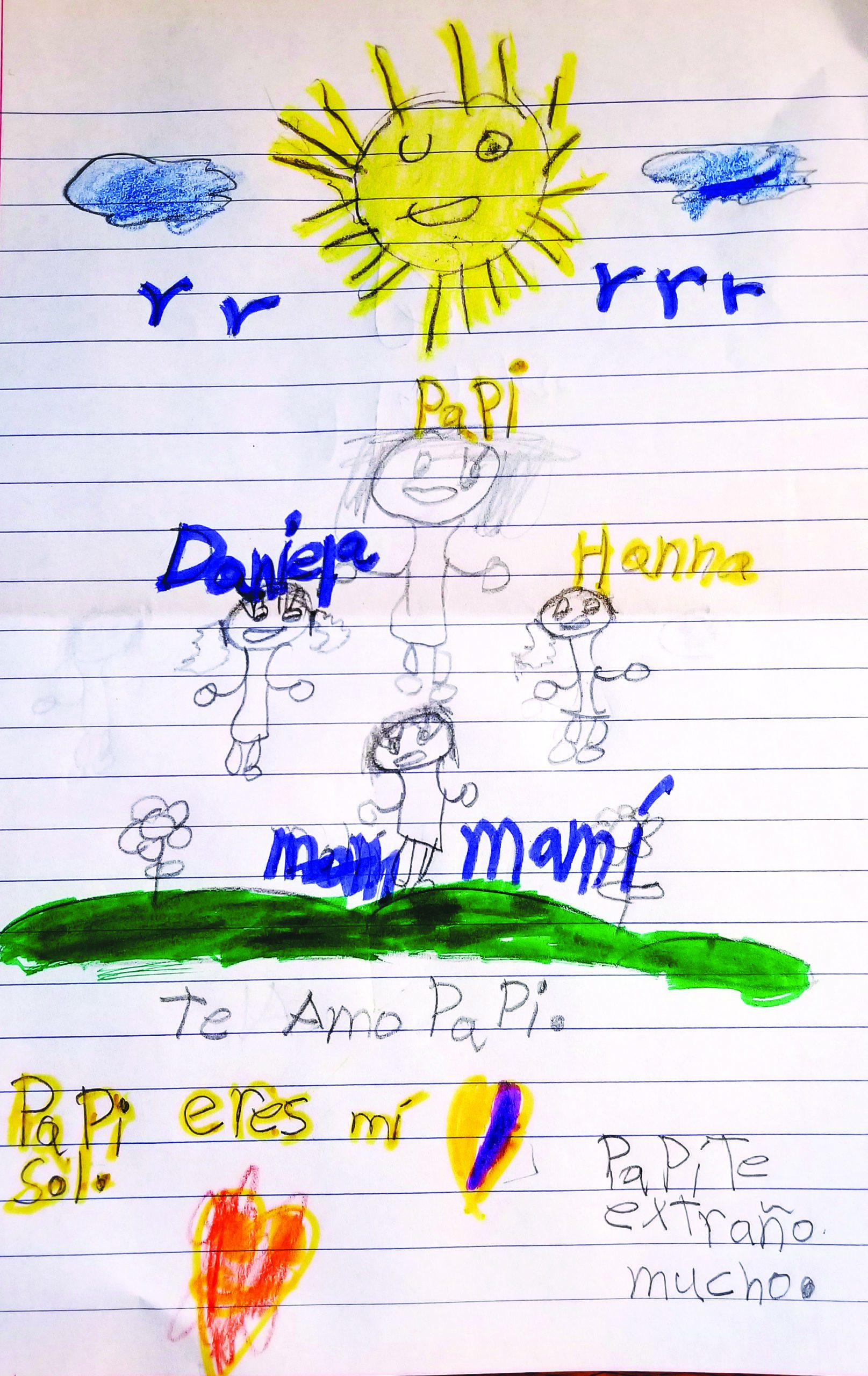

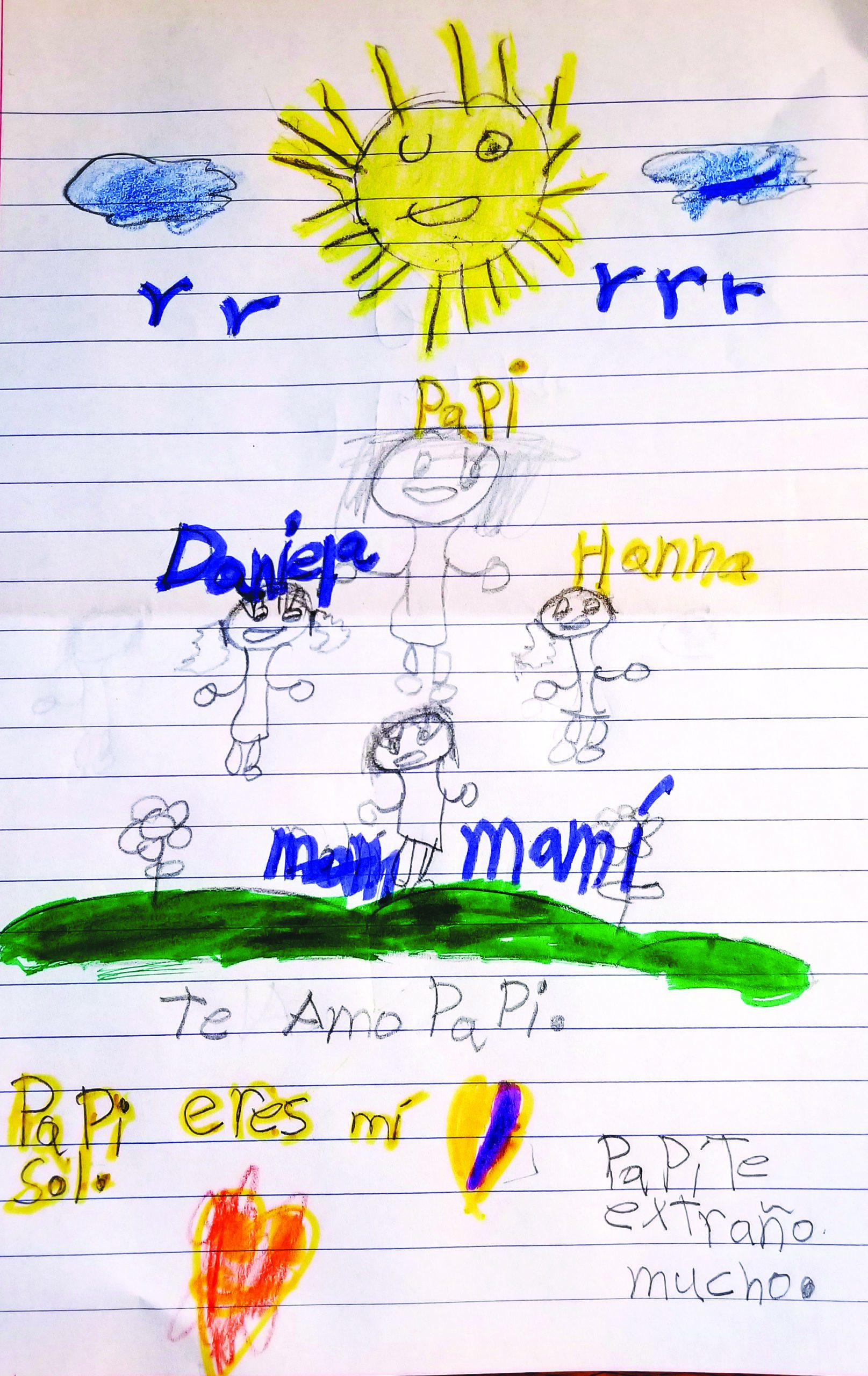

“My littlest girl could not remember me,” Adriel says, tearing up.

The family has been living with Abraham’s family, unable to work while they wait for their asylum request to be processed. They continue to submit paperwork. At the time of publication, Sofia has an appointment scheduled for March, and Adriel is scheduled for October.

Adriel remains grateful for the support they received from Covenanters.

“If Americans knew what was going on in the detention centers, they would respond,” Adriel says. “They would be broken in heart and soul.”

Donations for the Tirado family may be sent to Emmanuel Covenant Church, 17645 Saticoy Street, Northridge, CA 91325.

Please include a note that the funds are for the Adriel Tirado family.