Stories That Shaped My Faith

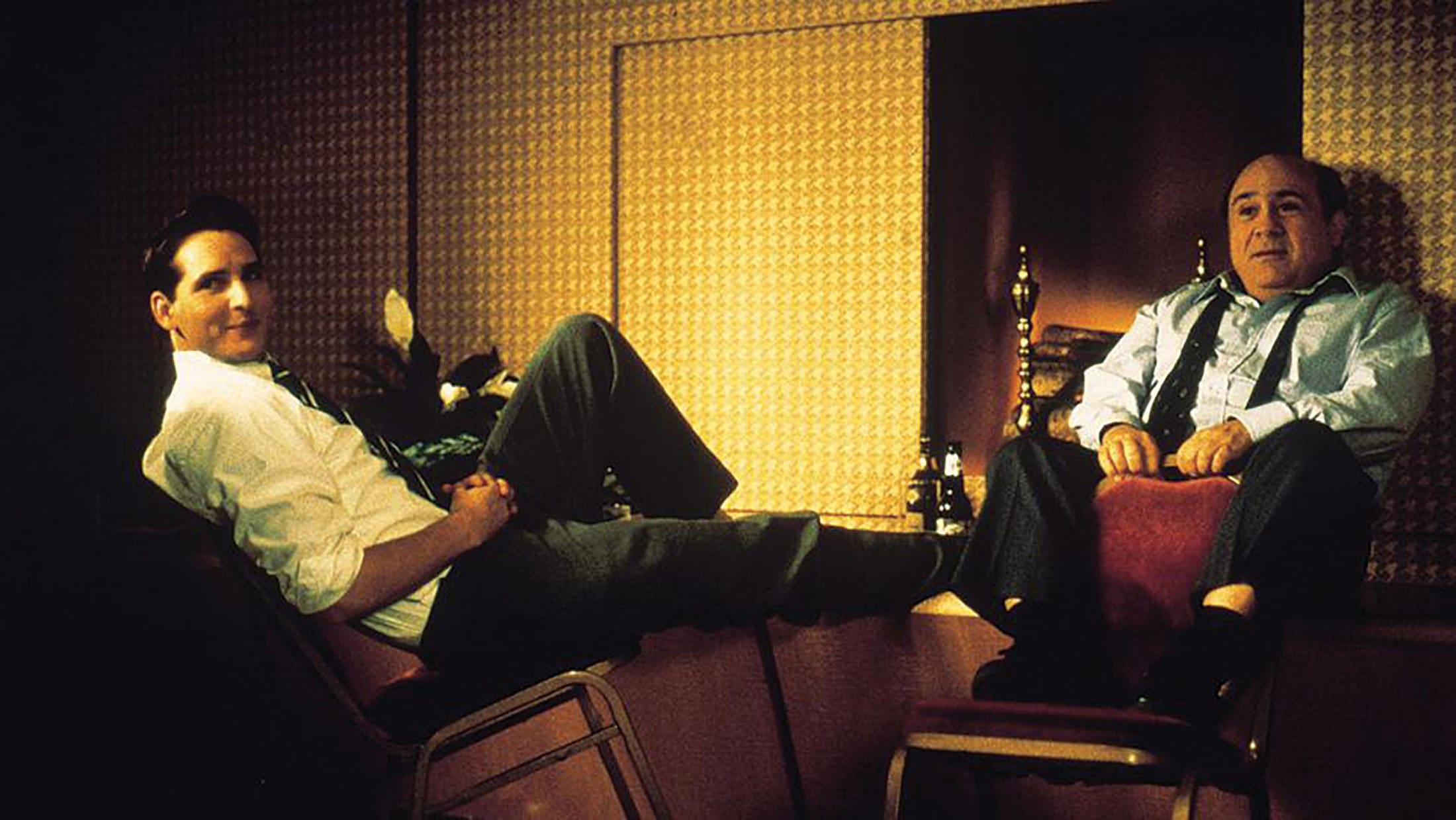

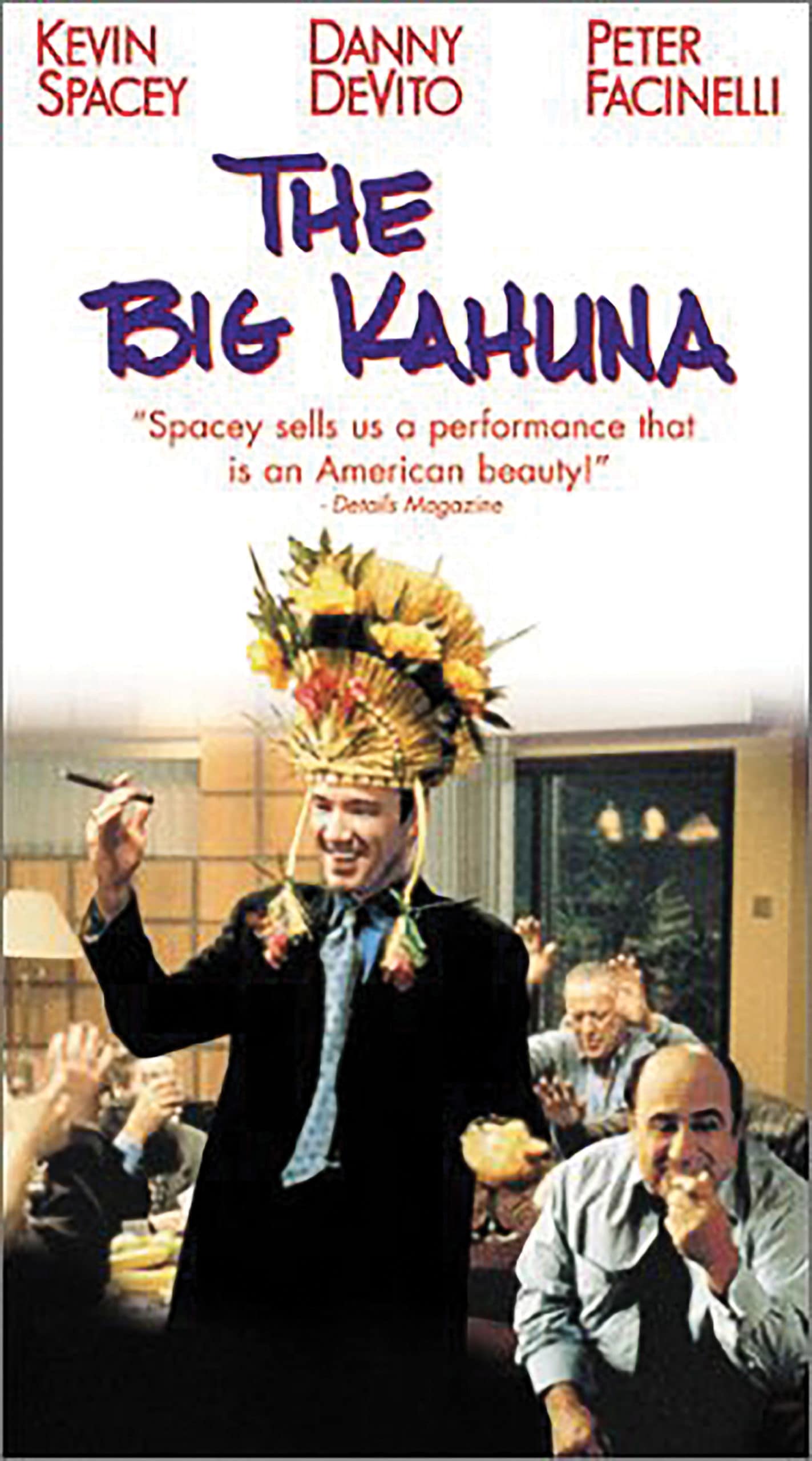

Ever since I first saw it, the 1999 movie The Big Kahuna has stuck with me. The film depicts two marketing reps—Larry Mann (Kevin Spacey*), an archetype of foul-mouthed hedonism, and Phil Cooper (Danny DeVito), a man living with regrets that he carries with a quiet wisdom. Attending a trade convention, the two colleagues meet Bob Walker (Peter Facinelli), a religious young man who works in the company’s research department. He has no experience making sales.

Ever since I first saw it, the 1999 movie The Big Kahuna has stuck with me. The film depicts two marketing reps—Larry Mann (Kevin Spacey*), an archetype of foul-mouthed hedonism, and Phil Cooper (Danny DeVito), a man living with regrets that he carries with a quiet wisdom. Attending a trade convention, the two colleagues meet Bob Walker (Peter Facinelli), a religious young man who works in the company’s research department. He has no experience making sales.

The three men spend the entire movie in a hotel suite, scheming ways to meet an important manufacturer (the “big kahuna”), so they can sell him industrial lubricants. Neither Larry nor Phil ever meets the big kahuna, but Bob encounters him repeatedly. The experienced pair try to coach Bob to do the barest minimum of a sales pitch but, instead, he keeps steering the conversation to talk about Jesus. The sale is never made, the conflict about making the sale eventually degrades into a physical altercation, and in the end all three go their separate ways.

This movie has captured my imagination, deeply impacting my sense of vocation as a pediatric chaplain. In the fall of 2015 I was participating in Clinical Pastoral Education (CPE) resident training to become a chaplain. My supervisor asked me what wisdom, beyond the Bible, might guide me. This movie was my response. At that time of my life, I had recently been shaken by my transition out of pastoral church ministry, and I wondered how I would be an authentic witness of God’s grace without a pulpit.

Toward the end of the movie, Phil has a conversation with Bob about “selling” Jesus, saying, “You preaching Jesus is no different than Larry or anybody else preaching lubricants.” He suggests that Bob ought to be more curious about others, continuing, “That doesn’t make you a human being. It makes you a marketing rep. If you want to talk to someone honestly as a human being, ask him about his kids. Find out what his dreams are. Just to find out. For no other reason. Because as soon as you lay your hands on a conversation to steer it, it’s not a conversation anymore. It’s a pitch, and you’re not a human being, you’re a marketing rep.”

Phil goes on to explain to Bob that character (and trustworthiness) comes from the way regrets in life impact us over time. “The question is, do you have any character at all?” he asks. “And if you want my honest opinion, Bob, you do not, for the simple reason that you don’t regret anything yet.”

We seem to be a culture that treats pain as the enemy.

Perhaps his words sound harsh, but I have to confess that I’ve watched my own faith become a pitch at times. Too often I want to seek an easy comfort, and I am tempted to spare people from the pain of regret, remorse, grief. Yet unspoken pain can never become hope. Rather, we need to make space for stories of regret to be shared so that healing can occur. If we take over the conversation prematurely, we risk hindering God’s work.

As a pediatric chaplain, I sometimes shudder at words I hear directed to parents and children. We may tell ourselves that we are providing comfort with our facile “words of hope,” but in fact, such words tend to communicate that there is no room for their painful emotions. We may try to provide a shortcut past the pain, but the right words at the wrong time and in the wrong way can add burden to the pain rather than offering healing.

An aversion to hawking Jesus like merchandise has slowly bloomed through my calling. To make the point plain, I am living in the shadow of acute regret and painful grief. I am constantly tempted to sell the perfect word to make it all better because the weight of seeing so much fear and sadness feels overwhelming. We seem to be a culture that treats pain as the enemy and so we try to inoculate ourselves against it.

If I want to be a healing presence, I must allow the pain to speak, to take root and shake the core. If I want to be an ally, I must believe the testimony of the oppressed without becoming defensive. If I am loving, I must be willing to respond when my passions may not feel loving at all. The dialogue between Phil and Bob in this film invites us as Christians into the painful discovery that steering conversations has more to do with our own anxieties and unacknowledged hang-ups than what is actually helpful or godly. Curiosity, even about pain, can be a natural antidote to those tendencies.

I have learned that Christians dedicated to discovery and surprise when walking alongside another person tend to be more trustworthy. Those conversations bear fruit. Bearing witness to someone else’s story makes us more fully human. Being present while they give testimony to their regrets yields growth that we couldn’t have imagined.

Bob’s attempts to pitch faith to the big kahuna rob both the kahuna and Bob himself of their humanity. When we do this, we obscure the gentle work of God along the way.

If you know the work of regret in your life, join me in the shadows. Listen to the preschooler with a life-altering illness, the adult with a terminal diagnosis. Listen for their resilience and treasure their anger. Listen and wonder, without intention to change, without intention to steer. Listen and remove the shoes from your feet. Where you are standing is holy ground.

*It’s important to note that more than 30 individuals have made allegations against Spacey in the midst of the #MeToo movement, ranging from harassment to attempted rape. This difficult truth leads us to wrestle with how we engage art—challenging us to name the brokenness of humanity while asking ourselves, “Is it still possible to find meaning in this work?” In this case, I hold in tension the evil of abuse with the fact that I would not have heard God’s call in my life the way I did without this film.