Called by God, Part I

How do we dismantle the stained glass ceiling?

by Erin Chan Ding and Cathy Norman Peterson | September 6, 2019 | See Part Two

When Stephanie Ahn Mathis began serving as co-lead pastor of West Hills Covenant Church, a brown-roofed building perched at the end of a cul-de-sac, a man approached her during her first few weeks.

She thought he had words of welcome.

Instead, he said, “I’m not okay with women in ministry,” he said as he welcomed her, “but I’m going to be okay with it because your husband’s co-pastoring, and he covers you.”

When Midwest Conference superintendent Tammy Swanson-Draheim served as lead pastor of First Covenant Church in Mason City, Iowa, one man would either leave or duck down in the pews when she preached.

The experiences of Mathis and Swanson-Draheim are far from unique. Many Covenant clergywomen have their own stories of being sidelined, overlooked, dismissed, or challenged as they seek to respond to the Spirit’s call on their lives.

Some encounters demean and objectify. Covenant pastor Cath Kaminski recounts an incident of preparing for a baptism. “Two of the girls were in bathing suits, and I was getting ready to enter the sanctuary, and this old man put his arm around me and said, ‘Are you going to wear your bathing suit too?’ ‘No,’ I replied, ‘I’m going to perform a sacrament.’”

Carmen Quinche says she spent months inviting a neighbor to her church, Comunidad Cristiana Pacto Evangelico in Los Angeles, which she co-leads with her husband. When her neighbor finally decided to come, she walked in the door, saw Quinche preaching, and “she never came back.” Quinche later found out her neighbor had begun attending a church led by a male pastor.

Mary Peterson, associate pastor at First Covenant Church of Omaha, says that when she was ordained, a friend wrote her a letter about “how I was taking people straight to hell.”

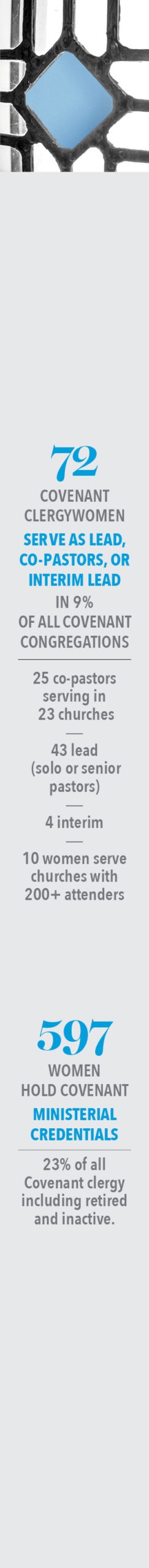

After 41 years of ordaining women in the ECC, only 72 Covenant clergywomen serve as senior, solo, or co-pastors of member Covenant churches, according to the ECC’s Ordered Ministry as of July 15. In other words, only 9 percent of Covenant churches have a woman as a lead pastor. Of those 72 pastors, only 10 are serving in churches with more than 200 attenders.

There has, however, been progress since 1978 when the Covenant ordained Sherron Hughes-Tremper and Carol Shimmin Nordstrom. Today, 597 women hold Covenant ministerial credentials, making up 23 percent of all Covenant clergy, including retired and inactive. Yet, just 12 percent of women who hold ministerial credentials lead or co-lead churches.

This is not just inconvenient—or damaging—for women seeking to fulfill their call to ministry. It impacts the entire church.

Swanson-Draheim, who also chairs the Council of Superintendents, says when Christians preclude women from living into their calls to lead and pastor churches, we limit the power of the gospel.

“You will hear occasionally people say this is not essential, or they will put it in the category of a ‘woman’s issue,’” Swanson-Draheim says. “It’s a gospel issue—the gospel of Jesus Christ. When we relegate it to some category of nonessential, then people can treat it in an entirely different manner.”

She asks, what are we teaching in our churches? “Are we teaching the complete gospel? Do we believe that what Jesus did on the cross was sufficient to restore broken humanity? Because when we decide that women don’t have the ability to fully live into their call, we’re literally saying that Jesus’s work on the cross wasn’t sufficient. We can choose to live in the shadow of the fall—or the light of the resurrection.”

Yet the obstacles are real. Sometimes they hinder women from recognizing or accepting their own call from God.

When God called Ramelia Williams to ministry, she ran from it—for ten years. She had crafted a career for herself in retail management and real estate, and she had no context to consider ministry.

It took revealing her pastoral desire to Debbie Blue, then-executive minister of Love Mercy Do Justice, for Williams to act on her decade-old call.

“She listened very well and deeply and affirmed the words coming out of my mouth,” she says. “It was the first time that what was happening in my soul, I was hearing as truth.”

Six months later, Williams started at North Park Theological Seminary.

Of the women in the Covenant who serve in senior pastor roles, Gail Song Bantum leads the largest congregation at Quest Church in Seattle, which draws approximately 750 worshipers each week. For decades, though, she did not want to be a pastor—not even when people told her as a child she was called to ministry—because she had seen her mother struggle too much.

Song Bantum’s mom had gone to seminary at the age of 40 and felt called to lead a church. She soon discovered her race and gender inhibited her ministry.

“In the Korean immigrant church, as a woman, she didn’t have a lot of support,” Song Bantum says. “Even my father gave her a hard time for it.”

Undeterred, her mother decided to plant her own church. She set out to find a church building where her congregation could meet. “For a year, nobody would rent her space because she was a woman,” Song Bantum says.

Finally, a white Lutheran congregation agreed to let her use their building on Sunday afternoons. Within nine months, the congregation had grown to 75 attendees.

Then, her mother died. Watching how she was treated, how much she had to fight, cut at her daughter. “For so long,” she says, “I honestly believed that the trauma of trying to live out her call killed her.”

In the Covenant Church, we believe the Bible teaches the full equality of men and women in creation and redemption. The ECC has long affirmed the full participation of women in all ministries of the church, and in 1976, delegates to the Annual Meeting voted to affirm the ordination of women. Two years later, the first two women were ordained.

The Covenant’s stand on women in ministry has attracted many pastors from churches that do not affirm women in their call to all areas of service. Cheryl Lynn Cain came to the Covenant after several years in a denomination in which, as a woman, she could write sermons but was not permitted to preach them. Called to Jesus and a life of ministry through reading a children’s Bible as a young girl, Cain says on Pastor Appreciation Day, staff “would come up to me and say, ‘Well, you know we consider you a pastor. We just can’t say it out loud.’”

ECC President John Wenrich often says he left another denomination in part because it did not ordain women. If women did not lead or pastor in churches, he says, “we wouldn’t have the full expression of the Holy Spirit. Every gift the Spirit gives to men, the Spirit gives to women.”

Wenrich told the 750 women attending the I Am Conference in July that men would “benefit by spending time sitting under the authority and leadership of women.”

“We hold to this conviction of co-leadership and gender equity not because of popular culture or political correctness,” he said, “but because of how we read the Scriptures together.”

Despite the church’s affirmation of women and ministry, societal barriers remain. The church is not unique in its restriction of women’s access to all areas of leadership. Of Fortune 500 company CEOs, just 6 percent are women, and only 2 percent of venture capital funding goes to women, according to Fortune magazine. The number of women in U.S. Congress is larger than ever before, but they still constitute only 25 percent of the Senate and 23 percent of the voting members of the House.

“When we decide that women don’t have the

ability to fully live into their call,

we’re literally saying that Jesus’s work on the cross

wasn’t sufficient. We can choose to live

in the shadow of the fall—or the light of the resurrection.”

Tammy Swanson-Draheim,

superintendent, Midwest Conference

and chair of the Council of Superintendents

Kaminski says, “During the 2016 election one of our faithful congregants—a guy I love so much—said to me, ‘Sexism doesn’t exist anymore because there’s a woman running for president.’”

But saying something doesn’t exist does not make it so.

Three decades ago, Covenant theologian Jean Lambert identified the impact of sexism in an open letter to Covenant women. “It is sexism when the only job available to a female seminary graduate moving toward ordination is at a rural crossroads 60 miles from the nearest hospital and five miles from any paved road. The problem isn’t her superintendent, her grooming, or her reputed emotional instability,” wrote Lambert, who was the ninth woman to be ordained by the Covenant and the first woman to serve on the Board of the Ordered Ministry.

She continued, “Women have a ‘right’ to be called and supported equally with their Christian brothers, but women are not, and changing the situation will require work.…Women will ‘pay their dues’ like their brothers, and then pay again, and again.”

When women are regarded as less capable than men, specifically in lead pastor roles, they often end up being called to small, struggling churches. In her effort to pursue every opportunity to do good ministry, a woman may accept a call to a church that isn’t thriving. However, the number of at-risk churches that genuinely turn around is statistically small. “Church revitalization is hard stuff,” says Becky Manseau Barnett, co-lead pastor of Highrock Acton, a Covenant congregation outside of Boston.

Sometimes the women pastors serving those congregations “look like they’re failing, and it affirms that bias that women aren’t as good at it as men. In fact, they were set up to fail.”

Sometimes the women pastors serving those congregations “look like they’re failing, and it affirms that bias that women aren’t as good at it as men. In fact, they were set up to fail.”

One challenge women face is a static understanding of what makes a good leader. Some people expect a booming voice and a male presence in their leaders. It’s a common complaint that behavior that’s perceived as strong leadership in a man can be viewed as bossy or demanding in a woman.

When she was 29, Kaminski accepted a call to serve a church in the Midwest as lead pastor. Once a congregation of 1,000 people, the church had dwindled to 70 weekly attenders by the time she arrived. She heard concerns on various fronts—she hadn’t been a lead pastor before, she didn’t have a husband, they had never had lead pastor who was a woman. “I’m not a risk,” she says, “but people saw me as a risk—single, young, female.”

Such bias is often deeply buried. “A man can preach and be adequate, or so-so, but we’re willing to give him more chances,” says Barnett. “But when a woman preaches and is so-so, we say, ‘Oh, I guess you don’t have a gift.’ It’s not malicious—most people are totally unaware they’re doing that.”

Greg Yee, superintendent of the Pacific Northwest conference, says he often observes female clergy being judged more harshly because “the same implicit bias that we talk about with race is applicable concerning women and leadership positions.” All male and female leaders, he says, need to help set a healthy tone and culture in churches.

“We need a culture shift,” Barnett says. “We are used to seeing a dominant, charismatic person in the pulpit, and we tend to understand the pulpit as the primary form of leadership for a pastor. But there are other forms of leadership that are just as, if not more, influential and important.”

Barnett grew up in a Baptist church, where a woman served as associate pastor. But that exposure did not erase stereotypes she herself internalized about ministers. “I had this particular picture of what a pastor was—he was a white male, and he led a particular way, with a particular style.”

Yet that picture didn’t match Barnett’s own gifts and personality. She describes herself as a helper who’s also highly relational—traits that are stereotypically feminine. “I just didn’t imagine myself in pastoral ministry.”

Eventually she realized she could care for people and serve them as herself, without trying to be somebody else.

“It’s not just a male-female thing,” she says. “This is about leadership styles and personalities and diversifying the picture of pastor for the sake of the gospel, for the sake of our image of who God is and what the church is called to be. As we get better at this, we’ll also get better at raising up men who are leaders, because all men are different too.”

Yet some congregations remain reticent about calling women to lead them because they still haven’t heard a woman preach in any regular way, if at all.

“There are always going to be people who have biblical arguments against women in lead or preaching roles,” says Devyn Chambers Johnson, co-pastor of Community Covenant Church in Springfield, Virginia, and founder of Four More Women in the Pulpit, a grassroots movement encouraging churches to invite four more women to preach than they did the previous year. “But I think the biggest hurdle is that having a woman in a lead role is different and unknown—and when it comes to church, people like what is familiar. Studies show that biblical arguments rarely change minds, but knowing female pastors does.”

Peterson, the associate pastor at First Covenant Church in Omaha, says she didn’t hear a woman preach until she was 27, at a Presbyterian church, and even then, conditioned biases fought their way into her head. “Afterward, I felt so guilty because all I could think was that her lipstick was a really weird color,” she says. “I

was so mad at myself for being so shallow.”

She came to recognize, however, that churches that do not allow women to lead or preach are “missing out on the voices that originally proclaimed that Jesus is alive. They’re missing out on hearing the woman at the well go back to her town and say, ‘Look what I found!’ They’re missing the timbre of those stories. I think they’re missing out on seeing how God calls all of us in unique ways. Leaders are not just white males with goatees and plaid shirts, you know?”

At the time she saw her first woman giving a sermon, Peterson had been enrolled at a seminary that wouldn’t allow her to take a preaching class. “I was going to have to take a public speaking class with only women,” she says.

She switched seminaries.

Swanson-Draheim says she didn’t hear a woman preach until she was 40 years old.

“It is really, really hard for our young women and girls to grow up and want to serve in ministry if they’ve never seen or experienced a woman in the pulpit,” she says.

Research shows that seeing women in ministry positions alters not only laypeople’s perceptions but also a congregation’s broader understanding of clergy and gender. Citing that data in her 2016 study on clergywomen’s experience in the ECC, sociologist Lenore Knight Johnson writes, “A paradox remains: if women’s pastoral presence alters the structure and culture of a denomination but that denominational culture and structure include significant barriers for clergywomen, how will change occur?”

Her challenge reflects a too-common experience among clergywomen. Jeanette Conver, pastor of Community Covenant Church in Essex Junction, Vermont, says, “I can’t tell you how many times I’ve heard Covenant leaders and superintendents say, ‘We’re a congregational form of government so we really can’t change churches.’”

At Quest Church, Song Bantum makes it a point to rotate responsibilities among the staff. She has the luxury of a large pastoral team, and she is intentional about including all pastors in planning the messages—not just the preaching team.

In addition, she invites other pastoral colleagues to do baptisms or preside over communion. “We’re always collaborating, asking, ‘what do you think about this?’ Or ‘what would be the challenge here, what should we not do?’” she says.

“The same implicit bias that we

talk about with race is applicable concerning

women and leadership positions.”

Greg Yee, superintendent,

Pacific Northwest conference

We can’t assume hearing from women in the pulpit is a box we can just check, says Kaminski. “We can’t say, ‘Well, we had a woman do this, so we’re all set,’ Or, ‘We’ve had four women in the pulpit, so we’re done.’” She emphasizes the value of preparing congregations to expand their view.

Search committees play a unique role in expanding women’s access to ministerial leadership. Conver suggests that committees have intentional conversations about whether they would call a woman before they begin looking at profiles. “If they don’t, then women get passed over because the committee doesn’t want disruption.”

Swanson-Draheim agrees, saying her conference has encouraged pastors to do studies with their congregations on women in ministry, using books and video resources such as the denomination’s Called and Gifted materials (available for download online). Male pastors also can cede their preaching slots to women.

It’s important to to start that work long before they get to the search process, because it’s often more difficult for a church to take a perceived risk once the process has started.

“By the time I am sitting in front of a search committee, it’s too late,” Yee says. “I am deliberate and clear with them (about considering a female pastor), but it was the responsibility of the last pastor to set that up. That pastor had the greatest power and opportunity.”

Laypeople have power to effect change as well. “They can make a huge difference by asking their male pastor to invite more women into the pulpit,” says Chambers Johnson. They can ask leaders and search committees to seriously consider women for pastoral roles. “And they can encourage gifted women in their own congregations to pursue ministry,” she adds.

Yet it is not enough to place the burden of change on congregations. Clergy can help pave the way by making the effort to mentor women who are entering ministry. Kaminski describes her experience as a young intern at Ceresco Covenant Church working with Jodi Moore. “She was intentional about mentoring her interns—and about preparing the congregation to come alongside me and letting me learn on the job. The job description reflected the responsibilities of the lead pastor, so I got to do everything. It’s the first place I was called ‘pastor,’” she says.

Chambers Johnson’s Four More Women in the Pulpit invites male pastors to make room for women, to intentionally share their power—and to model a willingness to learn from women.

“It does take intentionality to think outside the box and seek out women preachers,” Chambers Johnson says. “It takes humility to share the pulpit. Since beginning #fourmore, I’ve seen a renewed commitment by many male colleagues to listen to and support their female colleagues. And I’ve seen a renewed commitment of clergywomen supporting each other: mourning in our shared challenges and rejoicing with one another whenever possible.”

She heard from the Spirit,

“This is why I formed you in your mother’s womb.

This is why I’ve called you.”

Ramelia Williams, director of ministry initiatives, Love Mercy Do Justice

Williams, now the director of ministry initiatives for Love Mercy Do Justice, says men have a responsibility to speak with other men about women in ministerial leadership, and male pastors should normalize church environments in which women can preach and lead.

“You can’t just come into an environment that isn’t good soil, that isn’t tilled and ready to receive you so you can bear fruit,” says Williams, who also served as lead pastor at New Creation Covenant Church in Chicago and as intern pastor at New Community Covenant Church in Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood. “You can call me and plant me in rocky soil, but I’m just going to be a seed that sits on the top, and my roots won’t be able to go down deep in a way that I can thrive unless the ground has been broken up and it’s been made ready for me to stand in that place.”

Collegial support has become vital to the ascension and retention of women in pulpits. Swanson-Draheim says she consistently tells women, “You have to band together and support each other. You should never critique another woman anywhere, in any place. If you have a problem with something you need to go to that person, but do not do anything to denigrate other women.’”

Some needed changes must be systemic.

Some needed changes must be systemic.

Both Quinche, who says her role as a pastor “fills my heart and my soul,” and her friend Margarita Monsalve, lead pastor of Navegando con Jesus church in Torrance, California, urge changes not only in individual hearts but in corporate and congregational structures.

“Necesitamos cambios institucionales,” says Monsalve over lunch at the Brazilian churrascaria next to her church. “We need institutional change.”

She cites the need for supportive networks for women in the Covenant and for women to create opportunities for other women.

Peterson, who formerly served as president of Advocates for Covenant Clergy Women, and Swanson-Draheim are both advocating for a person in Develop Leaders whose sole role would be to focus on female pastors and on issues such as pay inequity. Lance Davis, executive minister of Develop Leaders, says hiring someone for the role is a priority; that person would collaborate with Marilyn Williams, the new director of women’s initiatives, whose job is to foster the flourishing of women across all five mission priorities.

Swanson-Draheim adds that the Midwest Conference holds women’s retreats for clergy women, “Called, Gifted, Here to Stay,” as well as “Exploring Call” retreats for women who are considering ministry.

When Conver entered the call process as she anticipated graduating from seminary, she felt the strikes against her—she was a woman and she was older than the other students. “I thought, no one is going to want me,” she says. Then East Coast Conference superintendent Howard Burgoyne told her how much she had to offer. “He said he was praying about me getting a call

to his conference. That’s one way a superintendent can be intentional.”

Cain came to the Covenant because a woman at a former church said to her, “If you don’t switch to a denomination where you’ll be ordained, you are actually doing more damage by perpetuating structures that diminish women. By letting them think this denomination ordains women because they see you there, I actually think you become part of the problem.”

She says the congregant helped her see that her call was about more than her own story. “When you have a justice or an equity issue, there is a bit of a burden that comes with being part of the community that’s looking for equity.”

The intersectionality of race and gender—Cain is Colombian-American and bilingual—added to her sense of responsibility. “In academia or ministry,” she says, “women who are Latina are not represented well.” Cain just graduated from the MDiv program at North Park Theological Seminary. Although she is not yet credentialed in the ECC, she is currently serving on staff at the Church of the Good Shepherd, a Covenant congregation in Joliet, Illinois.

Williams used to wear long skirts while preaching, so people would not see her legs shake and her knees knock. “Literally, with fear and trembling is how I would preach,” she says.

One Sunday, she felt such anxiety and weakness in her body she had to sit down before preaching.

As she started speaking, “I remember this intense moment of fighting with God, struggling that God was asking me to do what I was afraid to do,” she says. “I’m preaching and trying to connect with people with nerves running through my body, and in the midst of it, God broke through.

“The Holy Spirit stood up inside me and took the fear away, and I could see myself being a whole different person—who is still me—standing in that space.”

In those moments, as she spoke, she heard from the Spirit, who said to her, “This is why I formed you in your mother’s womb. This is why I’ve called you.”

After ten years of fleeing, God had given her clarity. She kept on preaching.

Jordan Cone, Stan Friedman, Linda Sladkey, and Jane Swanson-Nystrom contributed to this story.