Covenanters are practicing presence in their communities in the midst of crisis. In these stories, several share their reflections and experiences, inviting the church to join together on a difficult journey, with the hope of Jesus Christ to guide us.

When George Floyd was killed in front of Cup Foods in Minneapolis in May, racial tensions across the country spiraled out of control. But nowhere did they feel more real than in Minneapolis itself. Protests and marches turned into riots and fires, and clashes erupted between law enforcement and demonstrators.

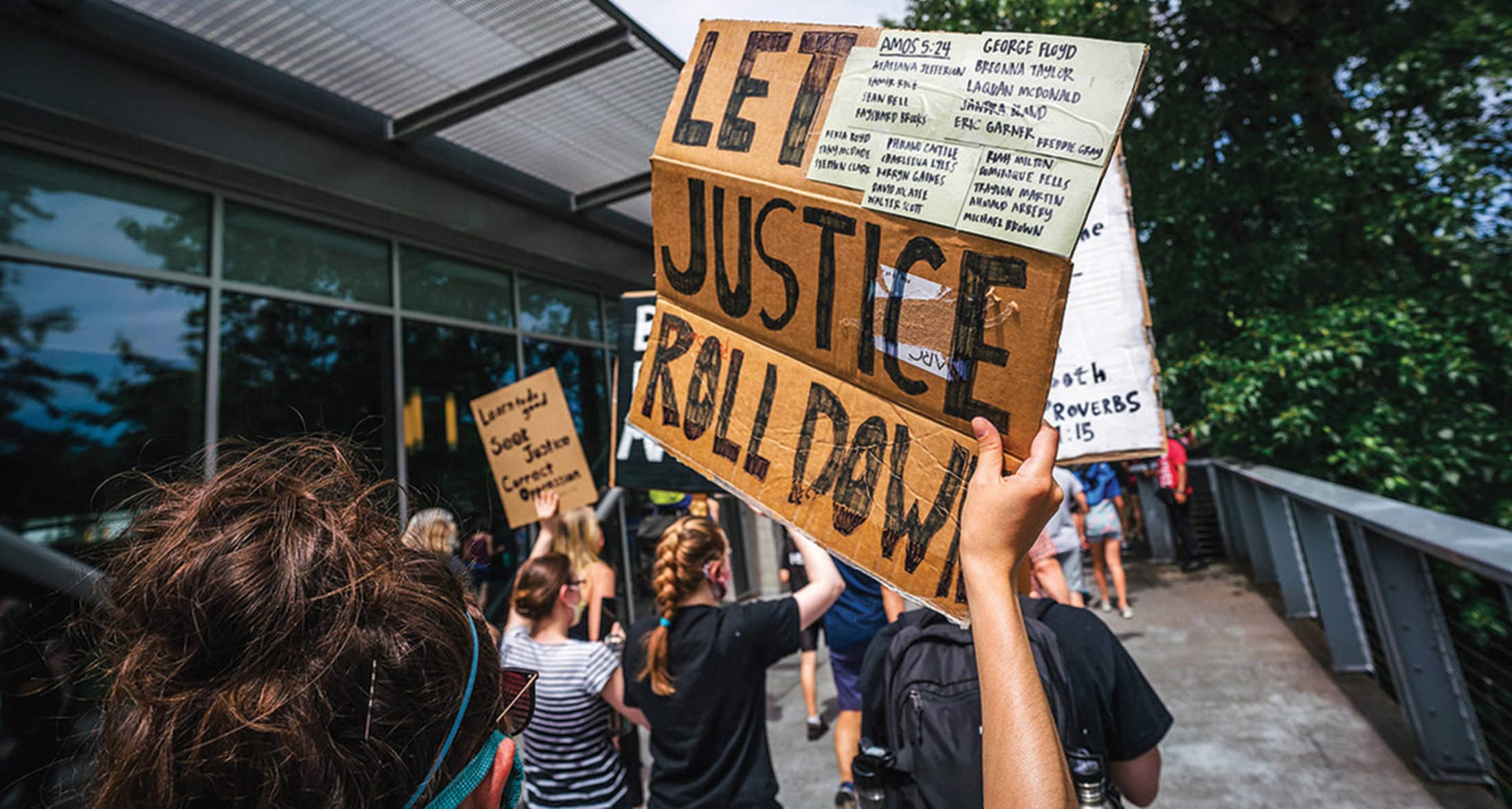

On Juneteenth, Radiant Covenant Church led a March to Surrender in Renton, Washington.

In the midst of grief, frustration, and outrage, local Covenant churches stepped in to serve their communities. When riots and looting shuttered local stores, the churches began distributing food, diapers, and cleaning supplies. So many donations poured into Community Covenant Church they had to clear out their sanctuary to make room. And Sanctuary Covenant Church hosted a peace barbecue that resulted in an outpouring of grocery donations.

At Destino Covenant Church, a congregation with a significant immigrant population, the scenes playing out in the surrounding streets mirrored all too closely the trauma those members had experienced in the countries from which they had fled. Grief and trauma counseling have been added to the spiritual and physical support Destino was already providing.

The pastors of these churches, Mauricio Dell, Luke Swanson, and Edrin Williams (pictured above), have stepped in to serve in the midst of crisis. They are standing in solidarity with their communities. They are practicing presence.

In the Covenant, we say we are in it together. We are relational people.

“As it is, God arranged the members in the body, each one of them, as he chose. If all were a single member, where would the body be? As it is, there are many members, yet one body…. If one member suffers, all suffer together with it; if one member is honored, all rejoice together with it” (1 Corinthians 12:18-21).

In these stories, we hear the voices of Covenant sisters and brothers, sharing their experiences, inviting the church to join together in a difficult and painful journey, with the hope of Jesus Christ to guide us.

by Paul Lessard

by Cecilia Williams

by Greg Yee

by Dominique Gilliard

by Michelle Clifton-Soderstrom and David W. Swanson

by Gregory Mesimore

by Dana Bowman

by Ramelia Williams

by Paul Robinson

A Lament: We Look for Justice but Find None

by Paul Lessard

On Memorial Day, George Perry Floyd, a 46-year-old African American man, was killed in the Powderhorn Park community of Minneapolis.

My first response, like many, was absolute disbelief that yet again, another Black man had been killed. The tragedy, coming on the heels of the deaths of Ahmaud Arbery and Breonna Taylor, brought anger and frustration about racism and systemic injustice to a boiling point in our country.

For many of us, it may be hard to know how and what to feel anymore. Months of home confinement due to COVID-19, plus all the racial unrest can feel like being repeatedly punched in the same place, over and over, a constant assault on the soul.

But our Black sisters and brothers are coping with this at a whole other level. Coupled with the outrage and anger is an overwhelming sense of loss and grief. For many the death of George Floyd has been nothing short of devastating.

Justice and righteousness are ongoing themes throughout Scripture, particularly in Isaiah: “We look for justice, but find none; for deliverance, but it is far away….So justice is driven back, and righteousness stands at a distance; truth has stumbled in the streets, honesty cannot enter” (Isaiah 59:11, 14).

The lack of justice, which is about systems and life lived together, and righteousness, being in right relationship with God and one another, stretch from beginning to end in Isaiah, a book that bears witness to 200 years of injustice.

Yet that pales in comparison to 400 years of the injustice of slavery in the United States.

We who are in the majority are called to recognize that much of the success of our country and even in many cases our ability to garner personal wealth, has come as a result of slavery and the oppression of particular people groups. Generational wealth is connected to property values, and African Americans across the country were consistently restricted as to where they could live, often in less desirable parts of our cities and towns. Have you ever wondered why the south side of urban centers in the Midwest always seems to house Black neighborhoods? It’s because most of the rivers flow south to the Gulf, carrying the refuse of the cities. Blacks lived literally downstream and downwind of those who are more privileged.

The call to action is simple and pragmatic:

White evangelical sisters and brothers, speak up.

The United States was on the verge of adopting universal health care in 1947, but segregationists blocked it out of fear that it would lead to integrated hospitals. Center for Disease Control data shows that Blacks suffer and die from the coronavirus at higher rates than whites, in every age category. But in the white community we often do not know these things or talk of them, and they are not taught in our schools. As a Black leader in the Covenant once told me, “I think white Christians only talk about this stuff when we are around and we bring it up, but the conversation dies when we are gone.”

We need to be mindful of inequity, in particular the inequity of voice and influence. I used to work for a university as an administrator, and one day a member of my staff, a student service adviser, came to me. She was frustrated by her inability to get a change made on a student record and asked me to contact the registrar’s office. In her words no one would listen to her, but they would listen to me, because I was the director. It made no sense to me that she could not get this taken care of on her own—she had the authority and it was a part of her job. But I called and the grade change was taken care of. She should not have needed me to make that call, but the registrar’s office—the system—would not recognize her authority. The point is this: Our African American sisters and brothers have been calling the registrar’s office for 400 years, to little effect. So we need to use the privilege we have to work to effect the change—to stand with them and move our society toward biblical justice.

The call to action is simple and pragmatic, yet potentially powerful and impacting: White evangelical sisters and brothers, speak up. Talk to your people. Make this conversation our conversation. Speak and advocate against racism in every form—systemic, corporate, and personal. Determine that you will no longer be silent.

When the Bible, our faith, and our places of worship are used as a prop by the white evangelical culture to maintain a status quo that allows justice for some and not for others, we become complicit when we say nothing. Our voices are needed because it is our battle too. This is about the kingdom of God coming here and now, the almost not yet kingdom of which we all are a part.

Hudson Taylor, English missionary to China and founder of the China Inland Mission in the late 1800s, once said, “China is not to be won for Christ by quiet, ease-loving men and women. The stamp of men and women we need is such as will put Jesus, China, and souls first and foremost in everything and at every time—even life itself must be secondary.” With apologies to Taylor, if we were to adapt that statement to our situation, perhaps we would say, “A just and righteous country is not to be won for Christ by quiet, ease-loving white men and women. The stamp of men and women we need is such as will put Jesus, biblical justice, and souls first and foremost in everything and at every time—even life itself must be secondary.”

Adapted from a service of lament held virtually at Covenant Offices a few weeks after the death of George Floyd.

The Word that Haunts

by Cecilia Williams

The phone rings. “Mama, may we come to your house tonight? We cannot stay at our house. We cannot breathe here.”

A dense fog and the unruly stench of tear gas had filled my daughter’s home a block or so from the scene of George Floyd’s murder. Her neighbors’ windows had been blown out by police flash bangs as forces haplessly attempted to quell uprisings. Scores of young people, finding no approved, acceptable outlet for their anguish, had poured onto the streets of Minneapolis. Something unwieldy, unsafe, unable to be contained had begun.

I recall returning to Minneapolis on the occasion of Philando Castile’s killing, four years ago. It had been only eight months since I’d made the same familiar trek around the place of the murder of Jamar Clark, a young man who had been a part of my church’s youth group. The gut-wrenching, heartbreaking pain of it whelms like a flood each time.

But this occasion somehow seemed different.

Perhaps it was the sheer duration of the event. The police officer knelt on the neck of a handcuffed, face-on-the-pavement George Floyd for 8 minutes and 46 seconds. Perhaps it was the strangely desperate and indescribably hopeless cries of young bystanders begging the officer to stop. “He is a human being. He’s dying. You’re killing him.” I was pierced by the calloused disregard for human life conveyed in an officer’s utterances, which betrayed his apparent, audacious assumption of absolute impunity. And then, there was the altogether too familiar refrain lifted once again into the unconcerned atmosphere… “I can’t breathe.”

So many words are now indelibly etched across our psyches and sensibilities from that horrific scene. But one outcry, for me, was far more haunting, one word pierced more deeply than the others.

With his dying breath, George Floyd called out for his mother. “Mama!” In a sacred invocation, his spirit summoned the one who had birthed him, nurtured him, embraced and comforted him. The one who suggested he could be anything and everything God had purposed him to be. Mama. The assurance of memory, the persistence of hope, “the sweetest earthly name” we know. As one observer eloquently reported, “To call out to his mother is to be known to his Maker; the One who through her, gave him life.”

Against my better sensibilities and amidst accumulating trauma, I forced myself to watch the video of George Floyd’s death multiple times. Compressed into the narrow frame of his last moments were images of a violent clash in belief systems, competing visions of sovereignty, ownership, and authority over Black bodies—and a most heinous, unmitigated lack of regard for the imago Dei in all of humanity. In that frame, I was challenged once again to confront the responsibility of being called into the divine sisterhood where belongs every African American mama with a Black son across history. Whether ours or another’s, each and every time, we are caused to bear grief, we are asked to persist through our own fear and despair, we are commanded to bear witness. It is our sacred charge. We are Black mothers.

While raw, hopeful moments of solidarity and community have pierced the smoke, simple outrage is not enough.

When that officer at last, after nearly nine minutes, got off George Floyd’s neck, the simmering pot of institutional racism finally boiled over in Minneapolis.

Now the world watches as my beloved home state—a state that denied justice for Jamar Clark, Philando Castile, and countless others—enters its moment of reckoning. It is a reckoning for a city that bills itself as progressive and tolerant, yet continues to sweep some of the largest equity gaps in the country under the rug. It is a city where inequity festers and simmers and waits. It is a moment of reckoning for a state, a country, perhaps for the world.

And it is a moment of reckoning for the church.

The rhetoric from the Christian community has, at times, been particularly desolating—partisan, divisive, devoid of the basic compassion of which our sacred texts speak. While raw, hopeful moments of solidarity and community have pierced the smoke, simple outrage is not enough. We must put those sentiments to work. While George Floyd’s precious life was singular, his murder was not, and we must not allow the shock of actually witnessing it to make it exceptional. We must muster the courage to tell the truth of what happened in Minneapolis—and tell it again and again. Changes to policing, changes to oppressive structures, changes in our country’s resolve erupted in an unprecedented way on the corner of 38th Street and Chicago Avenue in Minneapolis—and from there, sparked a movement all over the globe.

The phone rings.

I hear the voice of my son and my soul is (always) relieved.

“Mama, I think I have to go downtown and join these protests now. I know you probably won’t want me to go—but I don’t know what else to do. Something has to change.”

As my son headed out for peaceful demonstrations in downtown Los Angeles, I prayed for him and bid him safety. I asked that he call when he returned safely home.

And I recognize that it will be another sleepless night.

My son is a Black man in the United States. And I am a Black mother.

Where You Go I Will Go

by Greg Yee

When Michael Thomas, pastor of Radiant Covenant Church in Renton, Washington, shared with me his vision to organize a church-led march after the murder of our brother George Floyd, I was intrigued.

In the Covenant, the gospel work in racial righteousness has been a focus for more than 20 years. Of course I was intrigued. Michael and I are both leaders of color, we live in the same city and are friends. And Radiant has been discipling and incarnating the whole work of the church since their start seven years ago. How could I not be intrigued?

But intrigue can be cheap. Checking off the boxes of recommended reading lists and attending racial righteousness experiences does not extract a very high cost.

For years, I have been both proud and frustrated with our Covenant family in the area of racial righteousness. I’ve been proud of the genuine hard work we’ve done, of our willingness to stretch and learn, and of the beautiful growing mosaic of cultures and ethnicities that is the Covenant today.

But I’m also frustrated because we haven’t been able to break through to a level where our hearts are intimately connected and our commitments complete.

In the book of Ruth, when Naomi tells her newly widowed daughters-in-law to return to their people, to go back to a place that was culturally more familiar and safe, Ruth replies, “Don’t urge me to leave you or to turn back from you. Where you go I will go, and where you stay I will stay. Your people will be my people and your God my God” (Ruth 1:16). I long for such a rich, “Ruth-ian” expression and experience throughout the Covenant.

This is being family. This is solidarity. This is the expensive stuff. From Jesus’s prayer in the Upper Room in John 17, this is how the world will know that he is real. We know this today as the flow of resurrection power, filled with the Holy Spirit, launched in the church, and invited into God’s work.

We have made great strides in Covenant leadership and more than 30 percent of our churches are ethnic/multiethnic. But we still have a lot of work to do in our individual churches. As superintendent of the 74 congregations in the Pacific Northwest Conference, I long for us to cultivate the relational reflexes that jump without hesitation to the support of those who are facing hardship and injustice. Isn’t it natural to run to ensure the safety and well-being of our brothers and sisters?

I fought through my doubts as excuses rose. I knew our churches needed this. I knew I needed to reinforce kingdom culture.

When Pastor Michael shared the idea of the march with me, I immediately began processing how difficult it might be to invite the entire Pacific Northwest Conference to join him. At the time, we were in Phase 1 of reopening and the march would be in less than two weeks. We hastily gathered our area pastors on Zoom to gauge their interest.

It would be a stretch to pull it off, but I found myself deciding to submit to my African-American colleague who shared his convictions. I also had to make a decision about what was best for the Pacific Northwest Conference. I fought through my doubts as excuses rose. I knew our churches needed this. I knew I needed to reinforce kingdom culture in the conference.

I often remind our pastors to be faithful to their call as prophets and shepherds. Sometimes we need to speak difficult challenges to our people. Jesus himself said there are times when we speak and not only are our words not received but we ourselves are not received: “When you enter a house, first say, ‘Peace to this house.’ If someone who promotes peace is there, your peace will rest on them; if not, it will return to you….But when you enter a town and are not welcomed, go into its streets and say, ‘Even the dust of your town we wipe from our feet as a warning to you’” (Luke 10:5, 10). With that, sometimes we need to walk away—or let the other one walk away—and we must “wipe the dust from our feet” and move on.

The church was

not silent that day.

The church was

absolutely beautiful.

We also are called to be good shepherds leading our sheep up difficult hills by showing them the pathway forward. We don’t abandon our sheep. Yet sometimes they insist on not following, and they get snatched by wolves, like the weeds choking out plants in the four soils.

The pastors on that Zoom call brought us joy with their enthusiastic support. They committed to the event, and we came together unlike we have ever before. Representatives from 27 Covenant churches, more on the livestream, and 20 other Renton-area churches gathered for the March to Surrender on Juneteenth. On that day, the church led prophetically, declaring, “The church will not be silent!” It was a powerful outpouring to mark the start of a movement—a long needed movement from silence that has abandoned our Black family members and neighbors, to solidarity.

The church was not silent that day. The church was absolutely beautiful. I know that the experience of the body of Christ united, the clear message of the gospel of Christ, and the worship and prayers we lifted will be a foundation and fuel for the long work ahead.

A Light Unto Our Path

by Dominique Gilliard

Recently Efrem Smith, pastor of Bayside Church in Sacramento, California, tweeted, “The Bible is very clear in presenting sin as not just being housed in the souls of human beings but in the systems, structures, and institutions that they build and sustain.” When the Evangelical Covenant Church re-tweeted the quote, many responders online questioned the biblical legitimacy of his statement by asking the age-old Covenant question, “Where is it written?” While it is always right, and proper, to seek scriptural foundations for our theology, it is also illuminating and disheartening to see how quick many Covenanters are to respond with this challenge, before doing the biblical work of discovering what Scripture has to say.

Throughout Scripture, we see a pattern of leaders who do not fear God but are obsessed with earthly power. Pharaoh, Nebuchadnezzar, and Herod all succumb to sin and become tyrannical. When a leader’s individual sin is unbridled, it spreads like cancer into the systems, structures, and institutions they build and sustain. So, what began as one person’s individual sin metastasizes into structural and institutional sin, which legally leads constituents astray and results in the entire country becoming complicit with sin.

In Exodus we see how Pharaoh’s sin and fear leads Egyptian citizens into complicity with ethnic violence and oppression enacted against Hebrews, who were dehumanized, exploited, and enslaved to stimulate the Egyptian economy. A nation’s complicity with, and participation in sin is defined as corporate sin.

As the church, we are called to reclaim remembrance as a spiritual practice.

Biblically, corporate sin involves enforcing and adhering to sinful laws which explicitly oppose God’s will and harm our neighbors. Corporate sin is more than active participation in sin; it also includes apathy and complicity, or failing to act, in the face of evil amid oppressive contexts. This is why we liturgically pray for God’s forgiveness for both the things we have done and the things we have left undone. Martin Luther King Jr. addresses this in his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” speaking to the silence of white clergy amid Jim Crow oppression: “Never forget that everything Hitler did in Germany was legal.” He continued, “One has not only a legal, but a moral responsibility to obey just laws. Conversely, one has a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws.”

In fact, Scripture addresses corporate sin many times, ranging from xenophobia to the enslavement of one’s neighbor, the creation of ethnic caste systems that privilege some and disenfranchise others, the extortion of the least of these, infanticide, and idolatry. We see evidence in the empires of Babylon (Daniel 3), Egypt (Exodus 1:6-22), Persia (Esther 3), and Rome (Matthew 2). And God explicitly indicts Israel for its participation in, and complicity with, corporate sin (Micah 6) because it violates the covenant they made with God (Exodus 19:3-6, 10-12; Deuteronomy 4:6-8).

As I have studied history, I have gained eyes to see and ears to hear the depth and breadth of systemic sin caused by racism. My seminary education gave me a heart to respond and tools to articulate why the church must pursue racial righteousness. The only way to authentically heal our racial wounds and mend existing racial divides is through the gospel. This truth compels me to offer my life to God and to the church, and inspires me to zealously strive to help the church awaken to our potential as the hands and feet of Christ in the world today.

Empowered by the Spirit, we can become racism’s antidote, but this will require us to understand that racial righteousness is not merely a politically partisan call. Racial righteousness is a fundamental component of Christian discipleship. Rather than being a progressive agenda, racial righteousness is a kingdom summons rooted in who and whose we are. Racial righteousness is rooted in the imago Dei (Genesis 1:27).

The American church is in the midst of an identity crisis, and it is causing too many Christians to forsake Jesus’s instruction: “I give you a new commandment, that you love one another. Just as I have loved you, you also should love one another. By this everyone will know that you are my disciples, if you have love for one another” (John 13:34-35). By neglecting that call, we miss precious opportunities to bear witness to Christ through our love for one another.

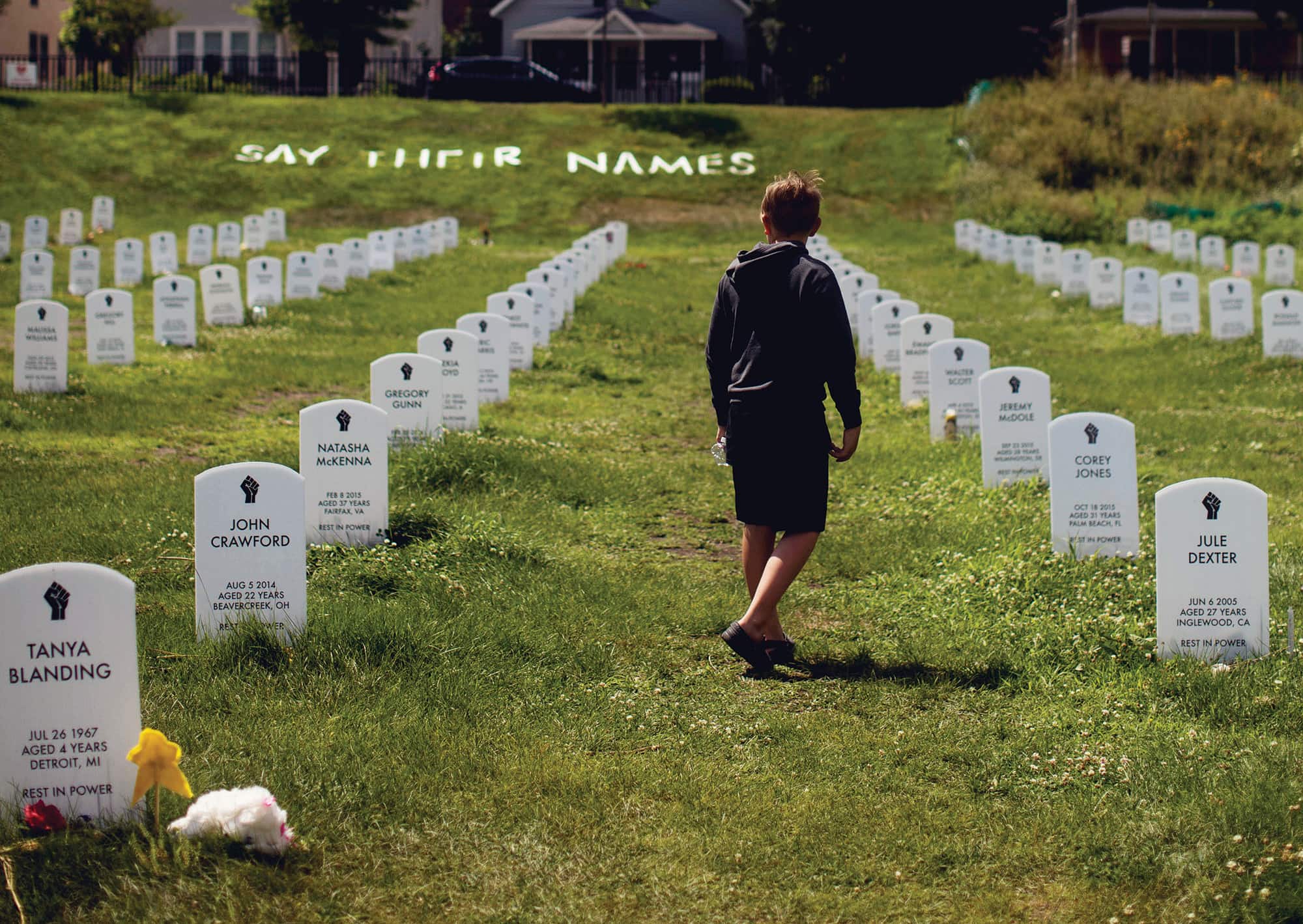

A clear foundational connection exists between identity and remembrance in Scripture. Consequently, the ahistorical nature of our theology is one of the primary challenges we face today. To heal the racial transgressions that fracture our land, we must remember, confess, lament, and produce fruit in keeping with repentance by turning away from our sins of omission and commission.

One reason I believe we have forsaken the spiritual practice of lament is because we have failed to heed Scripture’s call to remember. When we do not remember, lament seems unwarranted, pursuing racial righteousness seems optional, and the vital work of curating a common memory is forsaken. We see the effects of this within the Evangelical Covenant Church regarding ongoing efforts to repudiate the Doctrine of Discovery. A collective understanding of the genocidal violence and racial oppression the Doctrine of Discovery initiated would profoundly change the denominational tenor of this conversation. The racial divisions that continue to disjoint the body of Christ today are a consequence of sin and hardheartedness. We are too unwilling to confess the church’s culpability in corporate sin and to acknowledge how our ancestors’ sins continue to plague our land today.

Yet Christ calls us to do the hard work of curating a common memory that soberly articulates how racism, xenophobia, and white supremacy have distorted Christian ethics and discipleship in ways that infringe on the shalom God intended all God’s children to experience and the communion we were created to enjoy together.

As the church, we are called to reclaim remembrance as a spiritual practice. In the Old Testament alone, God instructs Israel to remember more than 100 times. Remembrance was the linchpin for Israel’s faithfulness. When Israel remembered, they were a faithful witness. When Israel remembered, they lived out of thanksgiving. They acknowledged that God freed them from slavery and called them to be a distinct people, set apart. God instructed Israel to live out of this remembrance and as a fruit of their remembrance, Israel was not to exploit migrant workers but to pay fair wages, not to deprive the foreigner or the fatherless of justice but to ensure that they made provisions for the poor, widows, and orphans.

Where many of us are today is not where we started, so let us have patience and grace with others who are doing the work but are still very much in process.

But when Israel forgot, they were just as prone to participate in, or acquiesce to, corporate sin as any other people and nation. When they failed to remember who they were, and whose they were, Israel created unjust systems and structures (Micah 6) that exploited the poor and the needy, and they mistook their chosenness as God always blessing whatever they did, even when they were covenantally unfaithful.

Scripture often ties corporate sin to generational sin.

- Israel corporately gathers to confess and connects its spiritual condition to its corporate complicity with sin and the sins of its ancestors. – Nehemiah 9

- The psalmist addressed culpability for the sins of Israel’s ancestors. “Both we and our fathers have sinned; we have committed iniquity; we have done wickedness.” – Psalm 106:6

- God speaks to generational sin, saying, “Because of their iniquity, and also because of the iniquities of their fathers they shall rot away like them…. If they confess their iniquity and the iniquity of their fathers in their treachery that they committed against me … then I will remember my covenant with Jacob.” -Leviticus 26:39-42

- Jeremiah connects corporate and generational sin, explaining that God requires Israel not only to acknowledge their own wickedness but also their ancestors’ sins. – Jeremiah 3:25; 14:20

- Isaiah speaks to corporate sin, declaring that he lived “in the midst of a people of unclean lips,” and warns that the Lord would repay “both your iniquities and your father’s iniquities together.” – Isaiah 6:5; 65:6-7

- Ezekiel links corporate and generational sin when he tells Israel to confront “the detestable practices of their ancestors.” Most of the chapter focuses on the judgment upon Israel due to the sin and unfaithfulness of its ancestors. – Ezekiel 20

We too have failed to remember, and this failure has led too many believers to cling to individualist responses to sin. Consequently, many Christians declare that we are absolved from any responsibility to repent of and tend to the systemic sins of our ancestors’ and the inequities their sins caused.

Rather than downplaying corporate and generational sin, or trying to absolve ourselves from the responsibility to serve as co-laborers with Christ reconciling all things, which includes not only broken people but also systems and structures, Christians should be leading the way in this pivotal moment. When it comes to advocating for racial righteousness and biblical justice, our elders and pastors can lead the way by confessing their own blind spots and the ways their discipleship has failed to attend to systemic sin, racism, and white supremacy. The point where many of us are today is not where we started, so let us have patience and grace with others who are doing the work but are still very much in process.

This is sobering work, but we do not do it in our own strength. We are empowered by the Holy Spirit, and Scripture assures us that when we stand firm, letting nothing move us, always giving ourselves fully to the work of the Lord, our labor in the Lord is not in vain.

An Equal Opposite Reaction

by Michelle Clifton-Soderstrom and David W. Swanson

People of color live with racism every day. For them, racism is not a matter of debate. White supremacy is neither elusive nor difficult to define, and it is not just political. Racism is both daily and generational trauma. It is not a relic of the past, and it is not something our Black and brown brothers and sisters can choose to opt out of.

White people live with racism every day too, but we have a much harder time seeing it. When it comes to our attention, rather than responding with empathy and solidarity, our instinct is often to debate, discuss, or deflect. We focus on the occasional hurt or confusion we’ve felt during discussions about race rather than on the systemic racism experienced by people of color. We are selective about which Black voices we listen to, prioritizing a few pundits who affirm our perspectives over the chorus who testify to the ugly legacy of racism and white supremacy. As white people, we often expend more energy on not being viewed as racists than we do lamenting the deadly impact of racism on Black, brown, and Native communities.

Whiteness is a power that benefits whites politically, economically, and socially. White supremacy is the positioning of white people and all that is associated with whiteness as the ideal. It rests on the premise that whiteness is the standard, and things associated with people of color are deviations from the norm. In Philippians 2, Paul emphasizes two movements that Christ embodies in the incarnation. First, he divests himself of the power of self-interest. Jesus empties himself of the thing that makes him most powerful—equality with God. Second, he is obedient to the point of death. This obedience is reminiscent of Jesus’s definition of love as laying down one’s life for another in John 15. In our racialized society, white Christians too often emphasize obedience while overlooking the call to humble ourselves in the pattern of Jesus: even unto death. Until white Christians understand the ways whiteness serves our interests, we remain complicit in arguably the deepest divide in the American church.

One year ago at the Covenant Annual Meeting, the ministerium passed a resolution committing to the work of antiracism. The resolution names the impact of racism on our ministerium and our denomination. It celebrates the biblical work in previous resolutions on racial righteousness and specifically names ongoing ways that white cultural dominance persists in the Covenant.

Approving a resolution is easy, but the follow-up work is much more difficult.

For some, the language in the resolution seems harsh. Others feel the resolution has silenced white voices, or they believe the ministerium voted to pass it without enough debate. Still others interpret the resolution as a form of public shaming. Yet Christ has entrusted the church with the ministry of reconciliation. To our white colleagues who may be struggling to understand the importance of racial righteousness and the role of antiracism in reconciliation, we offer words of encouragement and challenge in response to four common obstacles on the journey to racial righteousness.

Culture of Niceness. Covenant dominant culture emphasizes relational niceness, which often translates into well-intentioned efforts to make others feel better. This can be a pitfall of discipleship, however, because emotional comfort takes precedence over candid feedback that names sins and its effects. For those who experience discomfort, consider taking an approach of curiosity. Consider asking yourself, “What may I need to learn?” or “Whose perspectives have I previously misunderstood?” Curiosity engenders a posture of care, honors relationships, and creates greater openness to feedback.

Centering White Experiences. Beginning with curiosity helps those of us who are white avoid another pitfall that is common to the work of racial justice: centering our emotions. This happens when, after encountering new information about how racial injustice impacts particular people and communities, we elevate our own emotional responses, whether that be grief, shame, anger, or even skepticism. It’s not that the emotions of white people don’t matter. Yet, for too long they have drowned out the lived experiences of people of color. It’s possible to acknowledge the feelings that will inevitably arise on the journey to racial righteousness while still turning our attention to the realities faced by our friends and colleagues of color.

Claims of Moving Too Fast. The work of racial justice can seem overwhelming or as though things are moving too quickly to those of us who are awakening to the realities of racism. We easily slip into critiques of antiracist methods without learning why antiracist work is urgent. It can be easy to see antiracism as a program and racial righteousness as a “good idea” rather than as a matter of life and death and Christian discipleship. To counteract this tendency, white Christians can learn the histories of people of color in the U.S. as part of our purposeful narrative. We suggest clergy join the new pathways offered by the Antiracism Working Group of the ministerium and work with colleagues to convert learning to action.

Accountability. A genuine commitment to antiracism requires accountability. At times this elicits feelings of shame, because accountability to people of color is new to us. We encourage those who might feel this way to think about the social and systemic nature of racism, rather than focusing on racism as an individual problem. Society is not morally neutral, and white supremacy has a hold in our institutions, policies, schools, and government. It is helpful to acknowledge this impact on all of us. Also, embrace the discomfort of public accountability, and look for the ways the Holy Spirit may be forming you. Transformation rarely comes without the discomfort of being wrong or discovering our own complicity with sinful structures and ideas.

We recognize that approving a resolution is easy, but the follow-up work is much more difficult—so difficult, in fact, that it will take the ongoing collective will of the ministerium and the denomination to move in the direction of racial healing. It is our sincere hope that this antiracism work is one small part of the overall effort within the Evangelical Covenant Church to live into our identity as a multiethnic mosaic. Racial righteousness is not a ministry or a program—it is our identity in Christ. May we remain captivated by the beautiful vision found in Scripture of a people reconciled by Jesus across cultural lines of division and hostility.

The Silence of Our Friends

by Gregory Mesimore

It began with the release of the video of Ahmaud Arbery being chased down and killed by two white men, a dad and his son. It continued with the video of a woman in Central Park calling 911 to falsely accusing a Black man of assaulting her. It culminated in the murder of George Floyd, an unarmed Black man, pleading for his life as Derek Chauvin, a Minneapolis police officer, slowly strangled him in broad daylight while three other officers either looked on or helped pin Floyd to the pavement.

Massive peaceful protests catalyzed by these atrocities erupted. Some were accompanied by violence and destruction. These protests were not limited to major cities. Protests, most of which were peaceful, were held and continue to happen in cities and small towns across all 50 states. Others took place in cities around the world, people of all races united against the systemic injustice against Black people rooted in the American criminal justice system.

In the midst of it all, a seismic shift seems to be occurring. White America, particularly white Christians, are being forced to look in the mirror and ask, “How have I contributed to the racism that persists in our country, in our society, in my church, in my family…within me?”

The Oxford English Dictionary defines racism as “prejudice, discrimination, or antagonism directed against someone of a different race based on the belief that one’s race is superior.” By this definition, racism is mistreating people of a particular race based on the perpetrator’s consideration that such people are racially inferior. Based on this definition, I’m not racist—at least as far as I’m aware.

I don’t think of myself as racially superior to anyone. I don’t make jokes about African Americans or use the “N” word—ever. I grew up in the racially segregated South. I’ve seen racism. I know what racism is. I’ve seen the KKK, in their white robes and hoods, openly recruiting people across the street from the church in which I grew up.

If racism were fundamentally a political issue, I would have no hope. Look where our politics have gotten us today.

As a high school junior, I was bused to the one all-Black high school in my hometown of Greensboro, North Carolina. I was part of the first integrated graduating class from that high school, a minority white student in a class that was 85 percent African American. And I’ll tell anyone what a great experience it was for me to attend and graduate from James B. Dudley High School because it helped me confront my prejudice and the false assumptions I had about Black people. Ever since those high school days, I’ve considered myself “woke” when it comes to racism.

But. The problem is, I haven’t grown much in my understanding about racism since those high school days.

The problem is, because I don’t personally consider myself a racist, I have conveniently ignored all the ways the advantages of being white in America have benefited me at the expense of Black people—for all of my adult life.

The problem is, the Bible and the Lord Jesus hold me to a higher standard of obedience and life than the Oxford English Dictionary.

When it comes to the racism that exists in our society and in the church, I have remained complicit because I have largely remained silent. Taking comfort in the fact that I believe that I am not personally racist, I have basically, blissfully, lived my adult life doing nothing about the systemic racism that has benefited me.

The Bible and the Lord Jesus hold me to the standard of justice. They hold me to the standard of lovingkindness. They hold me to the standard of humility, servanthood, and sacrifice on behalf of others.

To be a part of the church of Jesus Christ and to be a follower of Jesus means I am commanded to work for justice, to practice lovingkindness, and to walk humbly with God. And that’s where my silence and my inaction in regard to racism convict me of my sin.

Martin Luther King Jr. famously said, “In the end, we will remember not the words of our enemies, but the silence of our friends.” Years ago my junior high social studies teacher taught me that silence about injustice is agreement with that injustice. Her words haunt me especially now: “Silence gives consent.”

I have thought of myself as a friend, even a brother to Black people. So why have I done basically nothing to ease the pain and right the wrongs and injustices African Americans face every day in this country?

Dahleen Glanton, an African American columnist for the Chicago Tribune, provided an answer to my question. To be honest, I did not like it, but I have no doubt that she is right. In her column on June 1 entitled “White America, if you want to know who’s responsible for racism, look in the mirror,” Glanton wrote: “(I’m talking to) those of you who see yourselves as intolerant of racism—those who were sickened by that video of George Floyd pleading for mercy. Too many white people are satisfied doing nothing to bring about substantive change. Admit it. You enjoy the opportunities and privileges that white supremacy affords you. Yet, you want to distance yourself from the racist individuals and systems that keep you at the top of the hierarchy.”

She goes on: “Regardless of how much you say you detest racism, are the sole reason it has flourished for centuries. And you are the only ones who can stop it.…Black people, for the most part, are powerless to stop racism. If we could, we would have done it a long time ago.”

Racism is not a political issue. It is a human issue. It is a sin issue. And as hard as that truth is for me to acknowledge for my own life, that truth gives me hope. If racism were fundamentally a political issue, I would have no hope. Look where our politics have gotten us today.

But if it’s a human issue, well, the Bible has an answer for that. If it’s a sin issue, the Bible has an answer for that too. Healing the ravages of racism, both personal and systemic, starts with confession, which leads to repentance. And it grows into faithful obedience—an obedience that values justice above my own comfort and conviction, and action above my past complacency. That gives me hope—even for me.

Adapted from a sermon preached on June 7 at Edgebrook Covenant Church in Chicago.

Active Duty

by Dana Bowman

It was mid-summer, and my little home town was responding to the world blowing up again. I was standing at my kitchen sink, downing some coffee, when the texts from friends started piling in.

“I’m heading to the protest march this morning if anybody wants to come.”

“Sure! What time?”

“Yep, we’re all going—meet you there”

“I’ve got extra water if u need”

In the morning sunshine by my kitchen window, my coffee cooled in its mug as I read and became very still. My friends were so excited, so ready to hold a sign and walk, to mask up and show up. To do something.

I was not.

I looked around, mentally tallying all the chores I had planned for that day. Re-pile all the piles on the dining room table. A basket of laundry that Sisyphus would shudder at beckoned at me from the living room. As chores go, they were pretty nonessential. The laundry could wait; it was always very patient that way. Nothing on that dining room table, amidst the flyers and Amazon receipts and board games, would change the world.

I also didn’t want to change the world that morning. I clunked the phone face down on the counter, suddenly irritated with these women and all their chirpy texts and plans and spontaneity. And so my next task pretty much sealed my fate for the rest of the day: I started another load of laundry.

About an hour later I finally chimed in: “Sorry—just now responding: I can’t today. Be safe! Good for u!”

My exclamation points seemed forced.

I am a white woman, middle-aged, living in the Midwest. I have a husband and two kids. Our family is firmly in the middle socioeconomic bracket. The majority of my Instagram photos are filtered just a teensy bit. They are of my two cats or of Bible verses scripted in pretty graphics. In sum, I fit in.

I am so very privileged. So much so that I don’t even see it, like those invisible fences folks set up on their wide, green lawns. Fences keep things in. And out.

There were lots of easy reasons why I did not want to protest. The most obvious—COVID-19—had already burrowed me into my home like a rabbit, only darting out of my house when absolutely necessary.

My introversion could also be blamed, I suppose. Crowds and noise make me flustered and anxious. So, introversion plus a pandemic provided a strong one-two punch of an excuse.

Also, my kids wanted to play Monopoly with me later, so there’s that.

But what really kept me home was I was ashamed.

My head-in-the-sand mentality had worked for me very well all these years. Suddenly I was ashamed of my comfort, and that the latest in the news was making me really uncomfortable, and I was amazed by that.

And then I was ashamed about feeling ashamed. It had been a long time since I’d been in that space. I pride myself on my authenticity. It’s one of the emblems of my sobriety, after all, and I’ve worked so hard to make sure my insides match my outsides. But it felt like participating in any sort of protest would ring untrue. It seemed fraudulent or forced, like my earlier exclamation points. I was not a protester. All my life I had followed rules and stayed within the lines. I lived within that bubble where all authority was good and law breakers were bad, and I made sure that my life never intersected with either. To now carry a sign and argue against the rules seemed false, like when a child is caught lying and only then starts to cry.

My head-in-the-sand mentality had worked for me very well all these years.

And on that Saturday morning, one final thought stopped me: It won’t change anything.

Enter my friend James.

James is a rap artist, a Jesus follower, a husband and father. I met him when he was running sound for a cable TV interview during my first book release. He wore hip, dark-framed glasses and was quiet. When he smiles, he means it. He is Black.

James and I met for coffee recently, and as I plunked myself down in front of him, I told him I wanted to understand. I wanted to listen.

And then I started talking.

Friends, if that doesn’t pretty much sum up white privilege right there, I don’t know. But he was attentive and patient while I told him I feel guilty. I feel like a fraud with naive ideas and a lot to learn. And I feel hopeless and sad. I feel afraid. And, I feel so very bad about all of this. “I wish I had marched that day,” I tell him as I stir my coffee and avoid eye contact. “I feel like a coward.”

James adjusts his mask, takes a long sip of his drink, and then puts the mask back on. He says, “But Dana, it’s not really about your feelings, is it?”

That’s when I finally shut up. I listened to listen, as James put it. I didn’t listen to formulate a response or a reaction. I just listened to his story.

James told me that he is so weary, that he has been asked, numerous times, to comment on racial tension and trauma. “I have turned them down,” he said. “I am just tired. I don’t need to talk anymore. I mean, the evidence is there and they can figure it out for themselves.” And then he tells me a bit about his childhood and how this isn’t new. And, that for every incident that gets recorded, for every video evidence that goes viral, there are five more without all those witnesses. “Five more families that won’t see any justice at all. I’m tired,” he says.

My eyes filled with tears. I asked him how he deals with all of this. What does he tell his children? He shrugged as if the answer is a given (and it is), “The gospel.” Life has no meaning without it, he says. Without it, he would devolve into bitterness—bitterness that would be earned. Jesus walks with James. And he walked with my friends on that sunny Saturday. He is right alongside the police and the justice makers. He walks beside us all. Jesus is the only sense in all of this. And his marching orders are clear and simple: “Seek me first, with all of your heart.”

As I started to understand what Jesus is asking, all my tricky feelings slipped away for a moment. To seek Jesus is to love him and love others. This is obedience, we know, but it’s also known as active duty.

“You know, you don’t have to march,” James tells me. “Start somewhere though. In your neighborhood. Or with your kids.” Or by writing.

Even so tired and sick of explaining, James keeps hoping for change, which is the harbinger of Jesus.

And that changes me.

Monumental Changes

by Ramelia Williams

In 1876, the Freedman’s Memorial monument was unveiled in Lincoln Park in Washington DC. The statue depicts a Black man named Archer Alexander with broken chains, crouching before Abraham Lincoln.

Controversy around the monument prompted Frederick Douglass to offer his opinion on statue symbolism. In a speech at the unveiling, Douglass said, “Admirable as is the monument…it does not, as it seems to me, tell the whole truth, and perhaps no one monument could be made to tell the whole truth of any subject which it might be designed to illustrate.” He went on to advocate that the statue be joined by monuments to other collaborators in the abolitionist movement for justice.

Recently the Mississippi state legislature voted to retire and redesign its flag, removing Confederate symbolism from it. Crowds of protesters have defaced and destroyed countless statues that memorialize the Confederacy, slave-holding leaders and colonial founders of our nation. As bronze and marbled memories topple in harbors and upon grassy knolls, we are left to ponder the destruction and dismantling of well-manicured recollections of our collective American history.

As the Civil War emerged, Alexander H. Stephens, vice president of the newly forming Confederacy, said, “Our new government is founded upon… its cornerstone rests upon the great truth, that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery—subordination to the superior race—is his natural and normal condition.” A statue of Stephens still sits in our nation’s U.S. Capitol Building where we make laws that aspire to perpetuate freedom and justice equally for all citizens.

Images, monuments, memorials, and statues tell the story of a people. They mark a legacy of lives and times that once existed in a particular place. In Scripture, as Joshua is leading the Israelites over the Jordan River toward the Promised Land, God commands them to remove 12 stones from the Jordan River so they could build an altar of remembrance. “When your children ask in time to come, ‘What do those stones mean to you?’ then you shall tell them that the waters of the Jordan were cut off in front of the ark of the covenant of the Lord….So these stones shall be to the Israelites a memorial forever” (Joshua 4:6-7).

God invites us to think about our practices, our false gods, and the idol worship we practice in our own culture.

In other words, the parents and grandparents would tell the story of the God who delivered them from oppression, enslavement, and shame. It would be a celebratory monument to the power of God to redeem and usher God’s people into new life and deliverance. And embedded in that remembrance would be the opportunity to share the struggle of what it meant to be an enslaved people who longed for their inherent right to freedom.

In Judges 6, we read that the people of Israel had done evil in the sight of the Lord by worshiping idols in the foreign land where they resided. The book of Judges speaks to the danger of assimilation. God consistently admonishes the people to go into the land, but not to worship the gods of the people. In part, God is saying, “I am sending you into a culture of people that is unlike you, but I want you to take with you the gift of who you are. Your God-reflection is on display to expose the people of the land to who I AM.”

But Israel is all too eager to assimilate into the religious idol worship practices of the foreign cultures around them, which were diametrically opposed to their own. So God uses his prophet Gideon to tear down the idolatrous Baal altars of the people of God. These Baal altars misrepresented the story of God by uplifting Baal as the god of fertility, weather, and the changing seasons. The idols encouraged human child sacrifice in exchange for fertility of the land. The altars of that false god represented genocide and human extermination. So the God of Israel declared they must be torn down.

Like Israel, we need to repudiate the false gods in our land—such as the oppression of people of African descent, ideologies of white supremacy, and lifting up whiteness over ethnicities of non-white immigrant origins. These are false constructs, devised to perpetuate a false narrative that whiteness denotes one who is smarter, wiser, more dominant, more powerful than all others. Confederacy, white supremacy, Black oppression, American racial social constructs—these are the false gods being worshiped when monuments to leaders who touted these concepts as ideal remain on American soil in public spaces. God admonishes the Israelites not to fear, not to worship or assimilate to the impotent gods of the land. Likewise, God also desires to set us free from the dangers of assimilating to a theology and culture that are opposed to the righteousness, justice, and supremacy of God.

In this season of racial trauma, heightened tensions, civil unrest, and protest, God invites us to think about our practices, our false gods, and the idol worship we practice in our own culture. These stand in contradiction to the freedom God calls all creation into.

Let’s Talk About It: FAQs on Race, Justice, and Culture

by Paul Robinson

Our team serving the Love Mercy Do Justice mission priority frequently receives emails and comments on social media threads—even more so recently in light of current racial tensions. This list of FAQs is not exhaustive, but it is a start. Our hope is to expand dialogue throughout the Evangelical Covenant Church surrounding these topics.

The mission of Love Mercy Do Justice is to “join God in making things right in our broken world.” If you have questions you would like us to tackle, please email us at Love Mercy Do Justice-xx@covchurch.org.

What do you mean when you say you are “doing justice”?

When we use the term “doing justice,” we mean we are working toward righting what is wrong in the world. Sometimes when people hear the word justice, they assume we are referring to social justice, yet in our work we make a distinction between social and biblical justice. One definition of social justice from the human rights sector is that it depends on four essential goals: human rights, access, participation, and equity.

Biblical justice fights for the shalom of people who are unable, or limited in their capacity, to advocate for themselves. Scripture calls us to fight for the rights of widows, orphans, and the poor—those who were considered vulnerable groups (Isaiah 1:17). Sadly, in addition to these populations, those who suffer under the weight of racism are included in the vulnerable groups in our society.

Our work pursuing racial righteousness is an effort to expose and fight against unequal treatment based on race. Love Mercy Do Justice-xx defines “racial righteousness” as a discipleship pathway that exposes the sin of racism and illuminates how we can honor God by faithfully loving our neighbor across lines of racial or ethnic difference. Racial righteousness empowers us to reimagine life together amid division, gives us tools to seek first the kingdom of God, and demonstrates that we are disciples of Christ through our countercultural love for one another.

When racialized laws such as Jim Crow laws were eliminated, didn’t we dismantle systemic racism?

No. The absence of laws legalizing discrimination does not automatically eliminate discrimination in practice, whether in individuals or in the systems they operate in.

Beginning 528 years ago with the Doctrine of Discovery and followed by 400 years of racialized terror and destruction, our country has a long history of discrediting the existence of the image of God—imago Dei—among non-donimant groups. We cannot expect to dismantle systems of racism after just 50-80 years of legal reforms.

Criminal justice journalist Radley Balko says, “Of particular concern to some on the right is the term ‘systemic racism,’ often wrongly interpreted as an accusation that everyone in the system is racist. In fact, systemic racism means almost the opposite. It means that we have systems and institutions that produce racially disparate outcomes, regardless of the intentions of the people who work within them.” Systemic racism doesn’t require laws, or even racists, to be maintained. The rules for how the system works are baked into the American narrative. It was built around bad policies and practices.

One example could be captured in the phrase “driving while Black.” In a recent survey of Minneapolis, researchers found that more than 50 percent of people pulled over for vehicle equipment violations were Black, even though Blacks make up only about 20 percent of the city’s population. Unfortunately, such policies and practices are sustained by ignorance, complicity, or resistance to uprooting them because we are conditioned to believe they are normative.

What do you think of the claim that bad policing is just a case of “a few bad apples”?

Systemic racism is never about just the laws or individual racists. The whole system is bad—soil, seeds, land, equipment, farmers, and the apples. For people in the majority culture, the justice system typically works exactly as it was designed to work. There is no incentive for those who benefit from an unjust system to change it unless they are called to something higher.

Yet as Christians, we do have a higher calling. Jesus calls us as brothers and sisters in the family of God to love our neighbors as ourselves (Matthew 22:39). Indifference or willful ignorance about the experience of family members not from our “immediate tribe” is inconsistent with the heart of the gospel, as we see when Jesus heals “outsiders” again and again (i.e., Matthew 12:9-13).

What is your stance on Black Lives Matter?

The slogan “Black Lives Matter,” or #BLM, is a statement recognizing that Black people have disproportionately negative experiences in American society, not the least of which is with law enforcement. While the statement asserts the value of Black lives, it is not an assertion rooted in exceptionalism that Black lives matter over and above other lives. One way to consider this statement through the lens of Scripture is this: Jesus was a Jew, but one could argue that he purposefully elevated certain Samaritan people, who were deeply unpopular within his culture (see John 4:4; Luke 9:51-56; 10:30-37; 17:11-19).

How do you respond when you hear people say, “I don’t see color”?

This statement is often an effort to convey the idea that “Your racial identity won’t make a difference in my interactions with you.” The problem with this comment is that Black, indigenous, people of color (BIPOC), and those with more melanin in their skin seldom have the ability to remain unaware of their racial identities in public.

God created people from all different nations, tribes, and languages—all of whom have their own ethnicity and culture. But it was human beings who attached value to the color of one’s skin. Humans created race—and racism. God created all human beings, we all share a common ancestry, and we know that every human was created in the image of God. If God created me to be the ethnicity I am and calls my existence “good,” why do some find it difficult to see what God has “wonderfully made”? In Revelation 7:9-14, we see a depiction of the kingdom of God with a multitude “from every nation, tribe, people, and language, standing before the throne and before the Lamb.”

I feel called to do something about injustice. Where do I start?

If you’re just getting started on the path of biblical justice, start with prayer! After prayerfully entering the work of justice, find opportunities to intentionally learn, listen, and self-reflect. Note that learning precedes action. Isaiah 1:17 says, “Learn to do right, seek justice, defend the oppressed. Take up the cause of the fatherless; plead the case of the widow.”