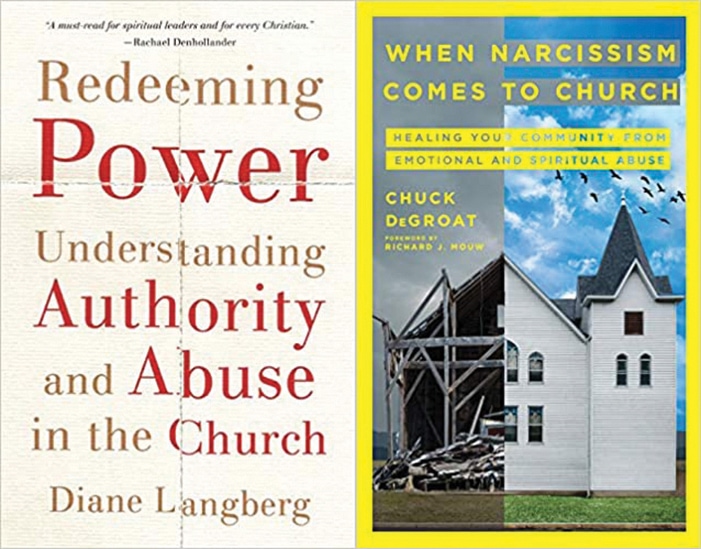

Redeeming Power

Understanding Authority

and Abuse in the Church

Diane Langberg

Brazos Press, 224 pages

When Narcissism Comes to Church

Healing Your Community from

Emotional and Spiritual Abuse

Chuck DeGroat

IVP, 200 pages

I’ve been intrigued lately by the account of Saul’s leadership in 1 Samuel 15. Samuel the prophet has instructed King Saul to attack the Amalekites and destroy all their livestock. Saul’s army, however, spare the best sheep and cattle.

Their rationale—that they only kept them to sacrifice to God—is flimsy. Even if they did make that sacrifice, the soldiers would likely feast on whatever meat the priests didn’t eat. Besides, doesn’t the work of combat entitle them to at least some reward?

Saul’s concession to the men might have made him a popular commander in chief, but it made him a disobedient king. So the Lord tells Samuel, “‘I regret that I have made Saul king, because he has turned away from me and has not carried out my instructions.’ Samuel was angry, and he cried out to the Lord all that night” (1 Samuel 15:11). Samuel had been there to anoint Saul king and now is grieving the consequences of Saul’s failure. He grieves for Saul, his family, and the entire kingdom.

When Samuel meets with Saul, he confronts him with these words: “For rebellion is like the sin of divination, and arrogance like the evil of idolatry. Because you have rejected the word of the Lord, he has rejected you as king” (1 Samuel 15:23).

This exchange serves as a cautionary tale. It tells us pride is tantamount to idol worship. The text sounds the alarm: arrogant leaders who set themselves against God, whether unintentionally or unconsciously, will be dethroned.

Unfortunately, there is no shortage of recent examples in American evangelicalism. The regularity with which these cases surface in the news may cause some of us to grow numb to these accounts. The stories don’t surprise us anymore. Ego, deceit, secrecy, bullying, power plays, and gaslighting among church and nonprofit leaders feel like the rule, rather than the exception.

The tragic result of these meltdowns isn’t just the damage they cause to the credibility of our ministries and the gospel they seek to proclaim. Very real suffering is inflicted on staff, volunteers, and supporters.

Our evangelical subculture needs surgery to address an often self-serving, toxic leadership culture. But effective surgery demands an accurate diagnosis, and this is where recent titles from Diane Langberg and Chuck DeGroat are helpful.

In Redeeming Power, psychologist and counselor Diane Langberg organizes her book in three movements: power defined, power abused, and power redeemed. In the first movement, she offers a biblical definition of the source and purpose of God-ordained power and explores how power is often corrupted by the church and church leaders. She describes the different types of power (verbal, emotional, physical, informational, absence, economic, spiritual, and physical) and their misuses.

Her section on power abused identifies how mishandled power affects human systems, relationships between men and women, dynamics between people of different ethnic backgrounds, church health, and the interplay between Christianity and culture at large. Langberg cites her own experiences and those of her clients, personalizing the stories of abuse victims and their trauma.

Finally, Langberg contrasts how the church has wrongly co-opted personal power with the way of Jesus. She calls both individuals and churches to self-examination, repentance, and transformation. And she reminds us that as the Good Shepherd, Jesus lays down his life for the wellbeing of the sheep, rather than manipulating the flock for pleasure or gain. Her invitation to intimacy with Christ and the pursuit of godly character first is simple, but not simplistic.

If Langberg broaches the subject of power in broad strokes, DeGroat narrows the focus to how narcissists inflict harm in local church contexts. DeGroat is a licensed therapist and spiritual director who teaches pastoral care and Christian spirituality at Western Seminary in Holland, Michigan.

DeGroat identifies narcissism as a diagnosable disorder, but he also recognizes that every person struggles with pride in our own lives, as well as a temptation to self-promotion and self-protection. In When Narcissism Comes to Church, he addresses both the personality disorder of narcissism and our own narcissistic tendencies as they emerge in the lives of leaders and laypeople.

In exploring the roots of this issue, DeGroat says, “Shame drives narcissism.” Many narcissists are running from the shame of past failure or the threat of future failure.

After describing how narcissism may manifest in each of the nine Enneagram types, the author offers a detailed list of some characteristics narcissistic pastors display: they feel threatened by competent people, they tend to withhold power, they lead through intimidation, and convey an insincere sense of vulnerability. He goes on to identify the forms spiritual abuse can take in a local church: silencing, certainty, experientialism, unquestioned hierarchy.

The first portion of the book helps readers identify and unmask narcissism in their own lives, their families, and their churches. The latter chapters point toward hope and healing. DeGroat contends that churches affected by narcissistic leaders are not “healed” when said leader leaves or is removed. Instead, such congregations must enter into a season of soul searching and truth-telling.

In his final chapter on transformation, DeGroat relays the story of a pastor he was counseling to work through issues related to narcissism and the abuse of power. He invited the pastor to ask his staff, “How do you experience me?” Posing the question—and being willing to receive the answer—is a risky proposition. But the exercise was a turning point in the pastor’s journey toward wholeness, self-awareness, and emotional maturity.

These books reveal the stark contrast between the way Jesus held power and the way our culture, including the church, tends to see it. We see the contrast depicted in Luke: “A dispute also arose among them as to which of them was considered to be greatest. Jesus said to them, ‘The kings of the Gentiles lord it over them; and those who exercise authority over them call themselves Benefactors. But you are not to be like that. Instead, the greatest among you should be like the youngest, and the one who rules like the one who serves’” (22:24-26).

In his book The Motive: Why So Many Leaders Abdicate Their Most Important Responsibilities, business writer Patrick Lencioni contends that healthy leaders “understand that…serving others is the only valid motivation for leadership. This is what annoys me when people praise someone for being a ‘servant leader,’ as though there is any other valid option.”

Unhealthy leaders, Lencioni writes, “see leadership as the prize for years of hard work and are drawn by its trappings: attention, status, power, money. Most people understand intuitively that this is a terrible reason to become a leader.”

These two books frame ways that power, rightly held, can be a gift to a church and a community. They are compelling and should be required reading for any pastor, church staff, church and nonprofit board members, and anyone who has experienced mistreatment from leaders in their church or family.