My phone jostled me awake near midnight with a call from a friend, “They broke the front doors of the church and there are still fires in the streets.”

On April 12, our church was one of many small businesses and large corporations damaged in citywide protests across Portland, Oregon. For weeks we had been hearing stories of broken windows and graffitied storefronts. Our church sits two blocks west of a police precinct where protestors had gathered almost weekly following the murder of George Floyd. And now in the wake of the killing of Daunte Wright, protests resumed.

I was called to pastor First Covenant Church in Portland in the midst of the pandemic and racial unrest of last year. Even though I hadn’t met most of the people in the congregation, we all knew we had reconciliation work to do, though it was hard to know what that work would be. Some joined the protests, standing side by side with our neighbors. Some began a journey of repentance, as they began to learn chapters of history they had not known. But this was our scattered, individual work. It seemed as if the pandemic had broken our collective witness, and we longed for God to make us whole.

Generations of families have come through our doors, out into the city, and around the world, working and witnessing to God’s gracious and abundant love. But sometimes God invites us into a new work.

Videos on social media of what happened the night of April 12 were haunting. Just steps away from the front doors of our church, police and protestors clashed in the street. In the heart of our neighborhood people threw rocks at one another, launched fireworks, dragged garbage cans into the street, and set them on fire.

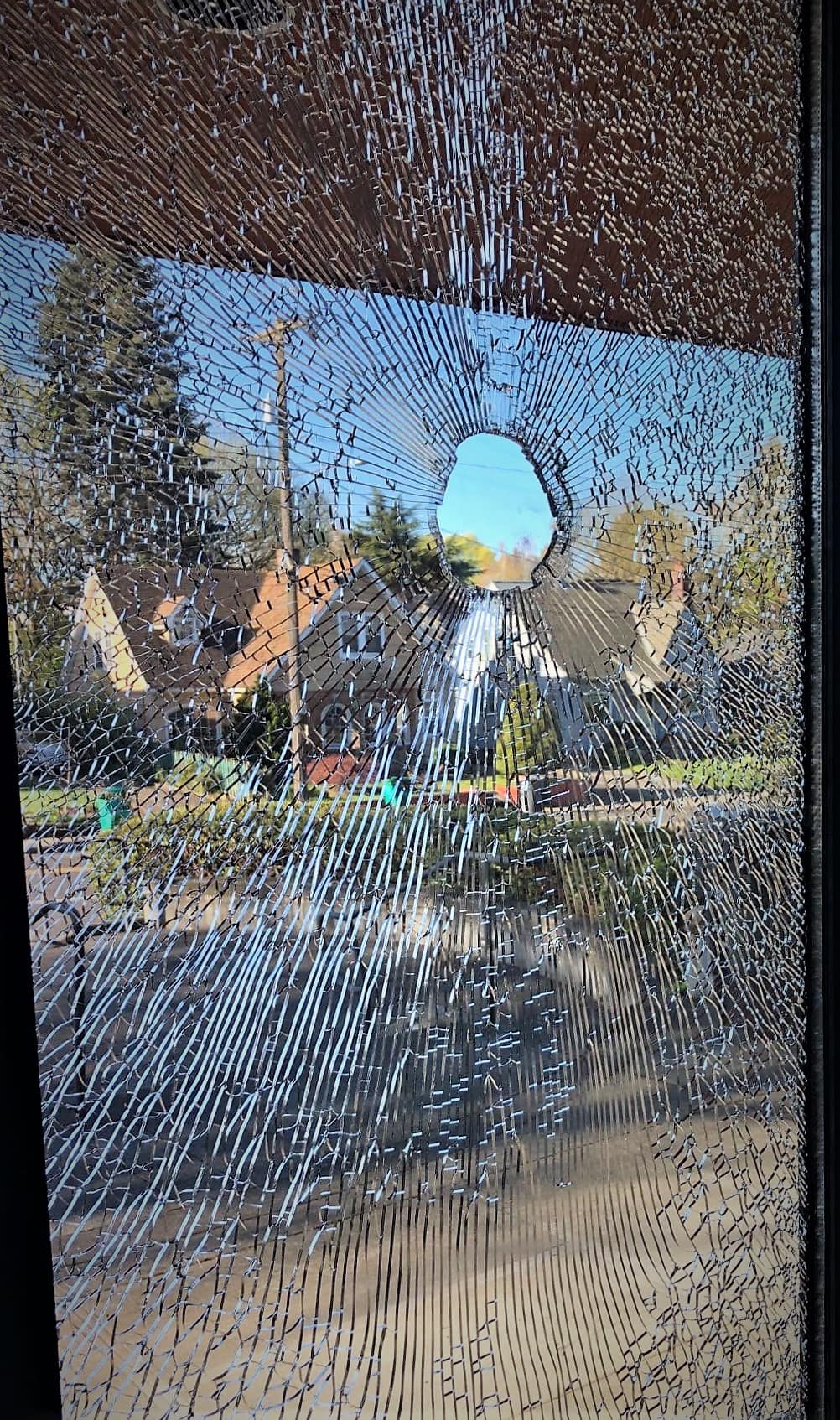

Against that backdrop, someone walked to the front doors of our empty church building. Hammer in hand, they smashed four clean holes in our four front doors. Just as quickly, they disappeared into the crowd and chaos. They did not attempt to enter the church, and no other part of the building was vandalized.

By the next morning First Covenant began to attract media attention. I had expected to quietly sweep up glass, but our little neighborhood church had been caught up in a war of competing narratives. In the minds of many, the protestors had crossed a line; it was one thing to smash the windows of Starbucks, but a church? That was an unforgivable violation—or so the story went.

When I saw the glass the next morning, I was relieved that there wouldn’t be much to sweep. The door frames had held the glass intact and the cracks hadn’t crumbled. I propped the doors open, sweeping the entryway as the sun started to crest above the rooftops.

On one door the cracks radiated from the center like fissures in a frozen pond. As the sunlight filtered through, I was reminded of stained glass—a geometric pattern of rectangles and squares, artfully arranged. The words of Leonard Bernstein came to mind: “I never knew that broken glass could shine so brightly.” The doors were radiant, unexpectedly beautiful.

The shapes of these cracks seemed familiar. Where had I seen this before? The longer I looked, the more the pattern came into focus. The perfect, empty circle in the center, the fractures spiraling from the center into larger and larger figures—It was the same pattern as Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s stained glass at St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, telling the story of the descent of the Holy Spirit.

Holding the image of the stained glass and the broken door before me, I could no longer see the doors as just an act of violence. Perhaps it was a sign of the presence of the Holy Spirit. Had God visited our church in destruction? Was God evoking something new in us?

This certainly is a gospel possibility. The story of salvation includes violence perpetrated against God’s own Son. The crucifixion makes way for the sending of the Spirit. Somehow God transfigures violence and evil, opening a door to life from within the heart of darkness.

In the empty space the hammer made, vandalism was transfigured into holy art. The broken doors symbolized God’s Spirit pulling us forward into a future we could not have imagined or predicted.

For more than 130 years, this small church in Portland has been a faithful and fruitful missionary presence. Generations of families have come through our doors, out into the city, and around the world, working and witnessing to God’s gracious and abundant love. But sometimes God invites us into a new work.

As Pentecost people, we know God may suddenly arrive in ways we did not seek or expect. God may call us into bold, faithful action that seems unfamiliar. God may ask us to give up more than we want.

This sign of God’s presence means we will step forward, working for justice and equity in our city. What was meant for violence, God has meant for good. With these broken doors, we see not destruction but a new kind of icon. In the center of this destruction is the space the Holy Spirit made, graciously shattering our illusions of security.

God is calling us from the silent sanctuary, into the streets of the city he loves as faithful ambassadors of reconciliation, his beloved peacemakers.