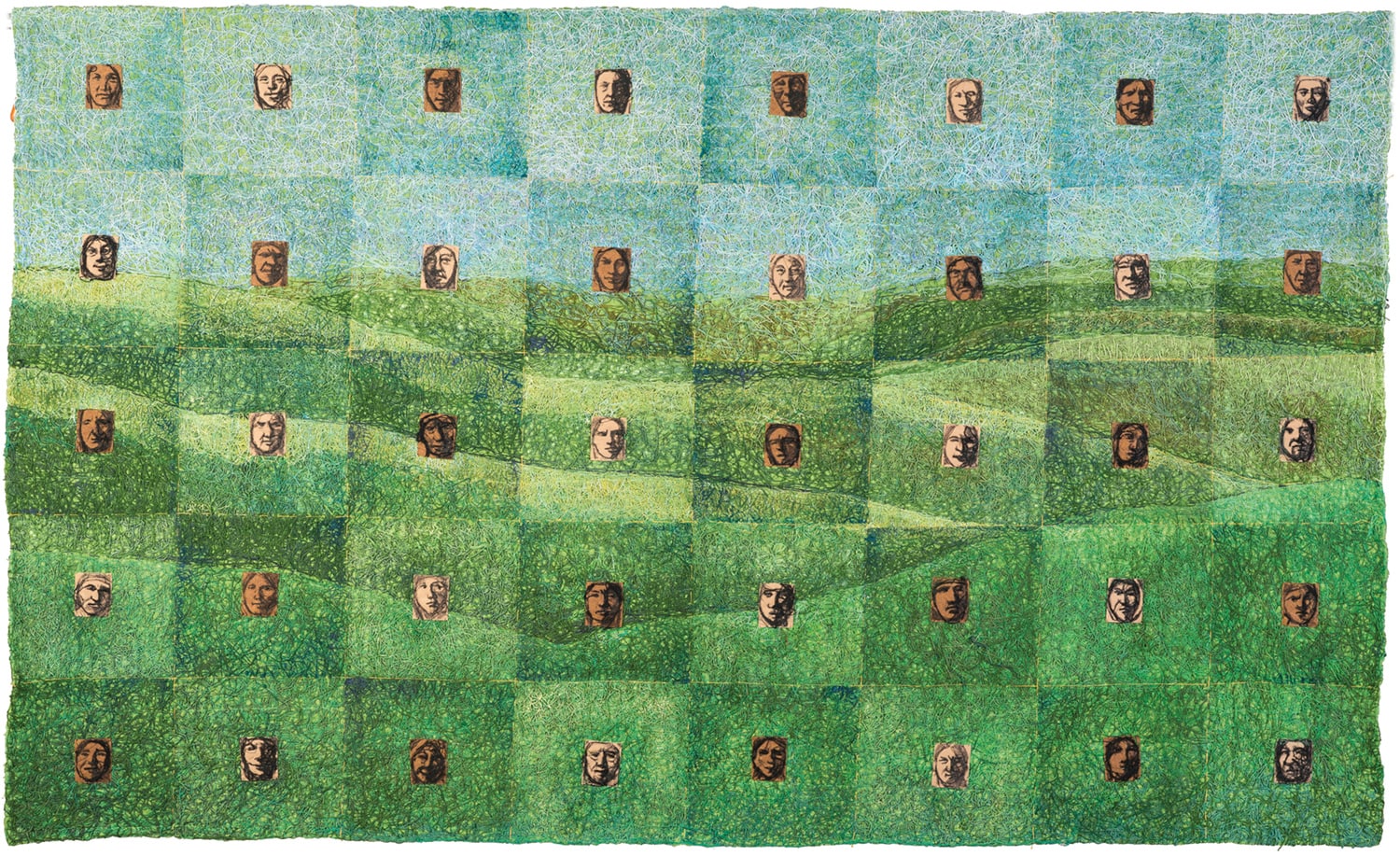

People of the Wind: People of the Wind, which is a rough translation of the Kansas Native American tribe name, is a collection of portraits of Indigenous Americans created by random stitching. The gold tones emphasize the hardships they have endured as well as the golden prairie grasses of their surroundings. Image transfer, dyed, painted, metallic paint, rust, patina, oil pastel, 60” x 40”

Turning Vulnerable Stories into a New Creation

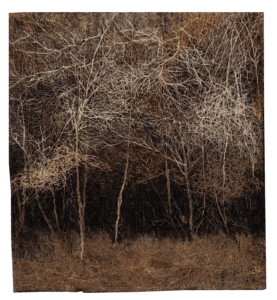

From across the room the image appears to be a very large photograph. As you approach, the edges soften and it becomes apparent you were mistaken. A painting, perhaps? Closer still, and you’re surprised to find the brush strokes are actually colored threads and recycled fabric in a textured 3-D maze of thousands of tiny stitches.

While Shin-hee Chin is an internationally renowned artist who is awarded and featured in trade magazines, the member of Countryside Covenant Church in McPherson, Kansas, maintains an unpretentious modesty concerning the works of her needle-pricked hands. She says she is just doing the work God created her to do.

The daughter of an English professor at the prestigious Seoul National University in South Korea, Chin says she felt cultural, familial, and internal pressure to study English—at the expense of her heart’s truest longing.

“I felt a little bit guilty when I spent time drawing,” she says. “So if I studied English hard enough, each night I gave myself permission to draw.”

When she was 17, while her peers were worried about studying for university entrance exams, Chin asked permission from her pastor to teach children at church. In creating Sunday school visual aids, she first discovered that God met her in that work. She says her art and listening prayer helped her realize, “This is who I am. When I do art, I become myself. And so I prayed to God that if I have talent, then I really wanted to go to art school. Through the art I want to grow. That was my prayer.”

Eventually, her parents gave her their blessing.

As she experienced the life of a “starving artist,” valleys of self-doubt, moving to the U.S., supporting her husband while he pursued a PhD in sociology, and raising children, she says God showed up again and again, sustaining her, imbuing hope, and helping her remain true to her life’s passion. She had earned a master’s of fine arts from Hongik University in Seoul, Korea, before coming to the U.S. in 1988 at the age of 29 and another MFA from California State University-Long Beach in 1998. At the age of 40 she became an art professor at Tabor College in Hillsboro, Kansas.

“For me, being an artist and being a Christian go together,” says Chin. “Art and spirituality serve similar functions in my life. Art uses visual elements to explore and communicate truth; spirituality is another mode of doing that. Both help me understand life and this world. While the feminine activity of needlework has influenced my choice in media and technique, my faith has shaped the concepts and themes in my work.”

Chin says, “My ongoing series of works explore humanity and dignity in human beings, highlighting their interconnectedness. I have also created a series of pieces that depict marginalized and forgotten people who have remained voiceless, faceless, and nameless.”

Her work has been exhibited throughout the world, including Washington DC; Tokyo, Japan; Hampton, Virginia; Geneva, Switzerland; Tainan, Taiwan; and Alsace-Lorraine, France; as well as her hometown of Seoul, Korea.

After the Korean War, Bertha Holt adopted eight abandoned children who had American fathers. She broke taboos around interracial adoption and eventually founded Holt International Children’s Services with her husband. Two types of fabric are interwoven and merged to create both mother and child.

Each piece is personal, born out of a process of wrestling with ideas and themes in prayer. Chin narrows down and weeds out, sketching and exploring mediums and materials to fit the concepts and message she feels compelled to portray in thread, paint, or scraps of recycled clothing.

While Chin often depicts human faces, she says she is determined to “portray the soul and what their life tells us about humanity.” This is true also for her depictions of nature, where rather than copying the form, she mirrors it.

“My message is more important than the image. At the same time, art has to speak on its own. It’s a tension,” explains Chin. “I want to make my art to be kind. Some art is arrogant. But I want my art to tell the truth about life, which isn’t necessarily always pretty. If we create something with good intentions, and tell the truth even though it is uncomfortable, it makes us think about humanity.”

She often has several works in progress at once. Even “finished” pieces may come back out from under the bed or up from the basement years later to find new life in an exhibit or venue that was waiting to give them life. In a sense they are “reborn.”

“When I choose to recycle an abandoned quilt, and then add stitches on top, I make new art,” Chin says. “I think about redemption through Jesus Christ and how all our souls can be saved—and then the medium becomes the message.”

She laments the ways world hurries us toward greatness, to find shortcuts to the finish line. Even paintings can be blown dry. But there are no short-cuts with hand-stitching. The slow, meticulous, steady rhythm of stitch after stitch allows time to re-examine one’s life prayerfully and intentionally. She finds meaning through this hard work.

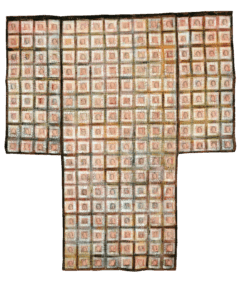

This gallery of inked female faces from the artist’s high school yearbook is created in the shape of a kimono. It recalls the tragic loss of innocence and life experienced by thousands of 10- to 18-year-old girls who were conscripted as sex slaves to serve as “comfort women” to Japanese soldiers during World War II. These voiceless, forgotten women are remembered by their Creator.

“Doing hand-stitching is more like a factory worker,” says Chin. “It’s not the master artist method; it’s more like I’m with the laborers and I can relate to the people in the factory through my work. I love that.”

“The process of arbitrary wrapping and stitching, which does not differ much from the variety of tedious and repetitive activities that preoccupy women at home, enables me to understand the dynamic, creative, and inspirational potential of the seemingly trivial and devalued aspects of women’s labors.”

To stay fresh as an artist, she turns to the ordinary routines of laundry, meal planning, grading papers, and even “artist dates.” Coined by author Julia Cameron, the term refers to dates with herself—activities with no purpose other than relaxation to make space for creativity. Chin may often be found wandering in second-hand stores while pondering the stories behind each donation or helping her husband in their backyard garden.

Chin admits that making new art or utilizing new techniques always scares her, but she invites those challenges because she doesn’t want to be a lukewarm artist. “I always challenge myself by putting myself in a vulnerable situation, in a field that I haven’t done before, but with a fresh mind.”

Chin was invited to exhibit a work on the 100th anniversary of women’s suffrage in 2020 for the Clinton Presidential Library in Arkansas. The Future Is Female portrays 12 women who have made significant contributions or demonstrated great potential in furthering global peace, equality, social and political rights, and environmental justice.

As a rule, Chin prefers not to depict people who are living, but rather to give voice to women who have been victimized or forgotten by history. The persistence of the Clinton Museum curator, along with the opportunity to challenge herself to see her art from a new perspective, persuaded her to portray living women in this piece.

She is not above ripping out several hours’ worth of handiwork, backtracking and starting over.

“My artwork is always mending—and my faith is too. I have confidence that I can be mended, awakened through my artwork, through my teaching too. I want my students to see something they didn’t see before.”

As the apostle Paul reminds us, “If anyone is in Christ, the new creation has come: The old has gone, the new is here!” (2 Corinthians 5:17, NIV). So too thread and fabric, whether found at a yard sale or in a second-hand store, may be woven by this master artist’s hands into something new. Shin-hee Chin has given her talents and gifts to the Hand who created her. Through her collaboration with God, we see God’s life in us being glorified.

For further exploration and inspiration, as well as videos of Shin-hee Chin at work in her studio click here >>