My Journey from Haiti to Hagar

The story of Hagar is a compelling story of a marginalized woman, a brown-skinned woman, a woman without status, a slave who was displaced, oppressed, unseen, and tired. Genesis 16 doesn’t tell us if Hagar had a “happily ever after,” but it does tell us that Hagar, the African maid of Sarai, got so close to God that she named him El Roi, the God who sees.

As I reflect on my life from the place where God has brought me, I realize that I am a prime example that God is in the business of elevating those who are not seen, who do not have voice.

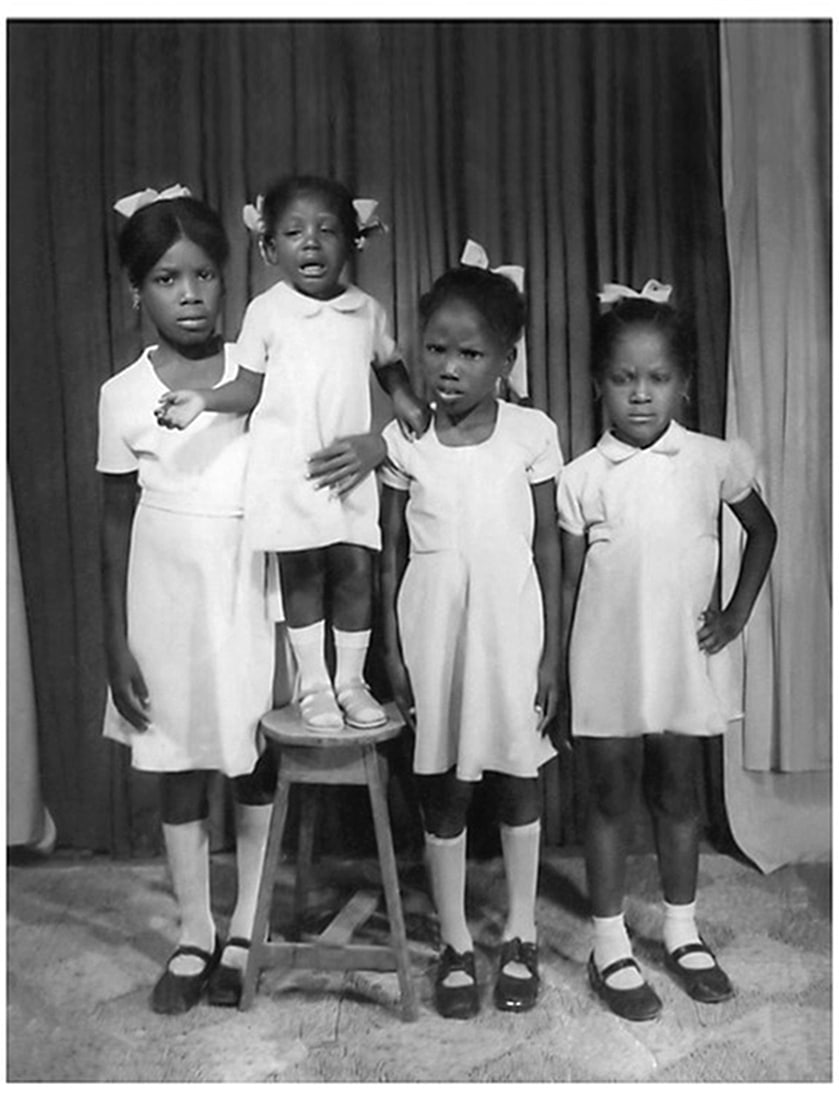

My parents immigrated to the United States from Haiti in the ’70s leaving my three older sisters and me behind to be raised by my aunt and grandmother. I was about one year old when they left.

Like many Haitians seeking to escape poverty and the lack of access to opportunities, my parents first went to neighboring islands—Saint Maarten, Puerto Rico, and Anguilla. Then they got a visa to come to the U.S. but when they overstayed their visa, they immediately began looking for a way to obtain residency status and send for me and my sisters to live with them. They had two more children while living in the U.S., which put them in a better position legally to send for us. I was about ten years old before they were able to obtain legal status and I could meet my parents again.

I never felt alone while living in Haiti. I was with my sisters, my extended family, and my community. We lived in the city with my aunt so we could go to school. During vacations, we spent two to three months with our grandmother in a more rural area.

While my older sisters and I were free to explore the outdoors and swim in the rivers along the coast of Haiti, my sister tells me that she and my brother, who were born in the U.S., were restricted to their apartment because my parents were fearful of everything. Living in a new country meant not knowing how to navigate the customs and traditions in this new land. While living in Haiti, we experienced poverty and lack of opportunity, but we were rich in other ways; we had a community where we felt known and belonged.

Haiti is a complex place. There is breathtaking beauty—majestic mountains, beautiful beaches, and lush vegetation. At the same time a broken government has perpetuated heartbreaking poverty, and communities like ours have experienced layers of loss. However, it was the church that nurtured our strength and hope.

Once a week we would fast and go into the mountains for hours to pray. Haiti is named for its beautiful mountains, which were the perfect place to call on the name of God. These weren’t just prayer services; they were lament services where we would cry out to God to show up in real and difficult circumstances. They taught me that God was truly all we had. We would sing, “Jezu se tout bagay pou mwen; la paix, la joie, la vie, se li ki fos mwen tou les jour.” “Jesus is everything to me; my peace, my joy, my life. He is my strength every single day.” I accepted Jesus as my Savior after one of those services when I was eight years old.

When our family was reunited in the U.S. and had become part of a Haitian immigrant community, the prayer services continued. Now it wasn’t just the adults crying out to Jesus; I needed the presence of God to help me survive in this new place.

We moved to New Jersey in the winter wearing strappy sandals and light dresses. We did not know how to dress away from our Caribbean weather. The language was different, the food tasted different. Eight of us lived in a three-bedroom apartment. We were no longer free to roam about as we did in Haiti. In school, no one could pronounce my name (“Jurla”). I spent a lot of time alone for the first two years because I didn’t know enough English.

I learned to pray. I learned to depend on Jesus. I learned that no matter the challenges life brought, I would make Jesus my default.

My parents found a Haitian church. That community was a saving grace. Members of the church had also immigrated from Haiti and we were all struggling through the same challenges. To be seen, to speak our language, to break bread together, and to offer support to one another was vital. And we prayed together.

The more I prayed, the more I fell in love with Jesus.

In elementary and middle school I was just trying to survive, but in high school and college, I started figuring out my identity as a Black woman and how I fit with other people of color. College was the first time I had my own room, my own bed. I met my husband, Fresnel, in our Haitian church, and we got married in my last semester of college. We had a son and then twin boys.

In the patriarchal culture we lived in, the culture I grew up in, there is no space for women in pastoral roles. Men led our churches and women took care of children’s ministry, women’s ministry, and all of the catering needs. So I followed the rhythm of my culture; I started teaching Sunday school to the children of our church.

One Sunday as I was teaching a group of four- and five-year-olds about Jesus falling asleep in the middle of a storm in Mark 4, I sensed a shift in me that said I would be in pursuit of this work for the rest of my life. It was both peaceful and disruptive. What would it look like for me to pursue teaching the Word of God to more than these preschoolers? How would I nurture this gift? Who could I talk to? Who could I trust? Would they take me seriously? I didn’t know what to do because I knew my church could not help me name my calling to preaching and pastoral ministry.

I had earned a degree in psychology in college, so I thought it only logical that I become a teacher. But after four years of teaching, something was still missing. I could not understand what God was doing in my life regarding my calling. Then God spoke loudly and clearly, calling me to attend Dallas Theological Seminary to work on my master’s in counseling and theology.

Before Dallas all we knew was the Haitian church. After moving to Texas, not only were we exposed to American churches, we now had to learn to navigate predominantly white churches. It was a major transition of cultural and racial differences. We blended in better with the African American churches, but there was still a learning curve for us culturally. It took us years to understand racial undertones, but it was a necessary journey. We needed to move away from our extended family. It was time for us to explore the rest of the world and to embrace God’s purpose for our lives. My husband found a job in Texas and I went to seminary.

When I was asked why I was going to seminary, I always said assuredly, “Not to be a pastor.” I focused on the counseling track. But after two and a half years of Bible and theology classes and seeing other women preaching, I could no longer deny that God was calling me to be a pastor.

At first, every door seemed closed. We ended up attending a predominantly white church where I got my first job as missions pastor.

Throughout my career in ministry finding spaces to minister where my race and gender are both celebrated was more of a challenge than I had anticipated. It posed a dilemma that I’m not sure I’ve yet resolved. I could return home to my Haitian community where I’m known and loved. However, home would not receive me as a pastor because of my gender. Or I could minister in a predominantly white church that is not structured to make room for a Black woman pastor. I often ended up feeling spiritually homeless.

But God has always found a way to move me onward to fulfill his mission. Friends from Dallas Seminary attended Redeemer Covenant Church in Carrollton, about a mile from our house and they invited us to attend a service. I became friends with the pastor’s wife and later started volunteering at the church. I was eventually hired as their associate pastor overseeing missions. I then went through the orientation process and became ordained in the Covenant.

Six years later, our children had all graduated from high school and we had an empty nest. We started feeling that we should return to our community in New Jersey and after a season of discernment, we moved back at the end of 2019.

I developed a deeper understanding of my calling when I was involved in a trauma healing conference in Kenya. I sensed the Lord calling me to work with women in the area of trauma healing. With the support of my husband, I founded a nonprofit called ElevateHer International, which does trauma training for women around the world. It has been eight years and I am still doing that work. We’ve been in Uganda, Kenya, Congo, Brazil, and of course, Haiti.

I’ve met many women of color throughout my journey and I can always tell when they are near giving up. Repeatedly I remind them that God is a God who sees. He hears our cries for help. He is the one who opens doors.

God took me, a little girl born in a village in rural Haiti, and allowed my feet to step into places and positions I could not have dreamed of. He has opened doors for me to see the world. I have been privileged to create platforms for women to heal from trauma, strengthen their relationship with God, and live purposeful lives. He’s in the business of elevating his children in order to display his goodness and love, especially for those without power and voice.

Hagar’s story is a lesson for women, Black women, and women of color in leadership and pastoral ministries who feel forgotten, lost, displaced, and tired. God sees us and God’s desire is to see his daughters flourish.