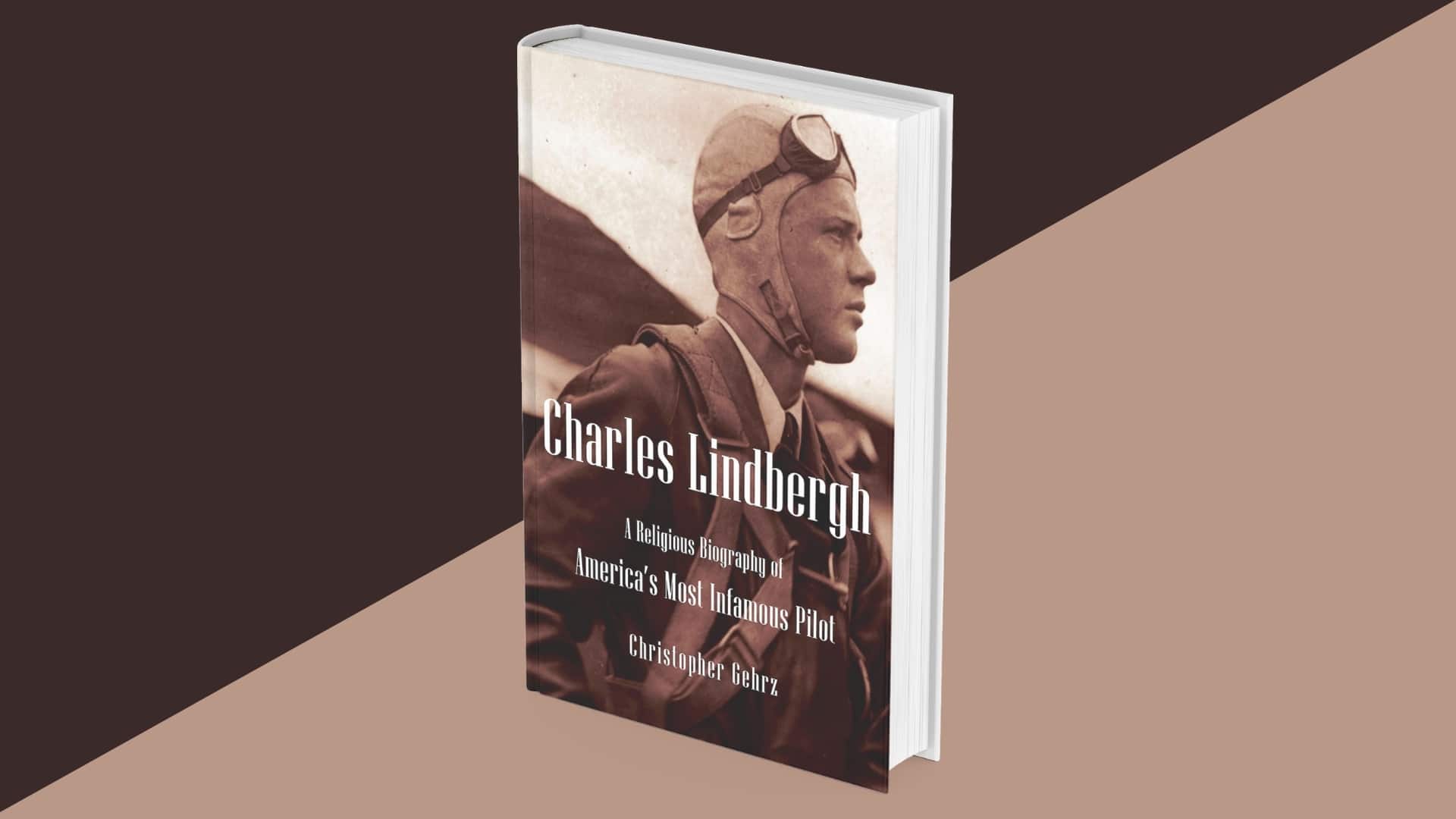

Charles Lindbergh: A Religious Biography of America’s Most Infamous Pilot

by Christopher Gehrz

Eerdmans, 296 pages

Little Falls, Minnesota, holds a special place in my heart. It is my father’s hometown and my wife’s birthplace. Generations of my family are buried in one of its cemeteries. Extended stays during boyhood summer vacations were the best. One visit included a trip to the Charles Lindbergh House and Museum. As a young boy, I entertained some awareness of Lindbergh’s historic flight, having read two of his autobiographies, We and The Spirit of St. Louis. I watched Jimmy Stewart’s depiction of Lindbergh in Billy Wilder’s 1957 film, The Spirit of St. Louis. In adulthood, my interest increased as I discovered other Lindbergh biographies as well as with Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s books.

Through all my Lindbergh Little Falls encounters—especially surrounding his last visit in 1973 to dedicate the new state park Interpretive Center—I sensed his spirit hovering over the town. The aviator was a rare visitor and occasional resident from another time, adopted by locals in a fit of civic pride. I realize that my annual or semiannual high-altitude appraisals of town life might not correspond with daily realities on the ground, yet I have a continuing sense that locals do not know quite what to make of their famous (or infamous) hero.

So I was pleased when I heard that Chris Gehrz, professor of history at Bethel University in Saint Paul, was contemplating a spiritual biography of Lindbergh for the Library of Religious Biography series published by Eerdmans. For Gehrz, “Lindbergh is best understood as a representative of the growing population of Americans we now refer to as ‘spiritual, but not religious.’”

Gehrz frames Lindbergh’s spiritual map with familial and contemporary references: “The child of a mother who questioned the veracity of the Bible and a father who found God in nature, he has much in common with the increasing share of ‘nones’ who grew up with no church background: people who had no particular childhood religion to renounce but followed their own path to an adult spirituality.”

The biography is framed around a question familiar to me in the person of another seeker from an earlier time, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (who lost family members during World War I and died three years after Lindbergh’s flight). Like Doyle—who cast aside Sherlock Holmes to the bewilderment of friends and fans in favor of a spiritualist quest which lasted to the end of his days—Lindbergh’s experiences during World War II “tempered his earlier enthusiasm for science, technology, and even aviation itself.” Gehrz observes, “All these decades and biographies later, nothing remains less known about this most famous American than the story of his spiritual quest.”

Why, he goes on to ask, would Lindbergh “spend so much of the last thirty years of his life writing about metaphysics, theology, and spirituality?” This book is the course Gehrz charts to answer that question.

Along the way, there are several beacons and at least one co-pilot. “Anne Lindbergh was both a key influence on Charles, encouraging and shaping his fledgling interests in literature, art, philosophy, and religion, and a particularly close and perceptive observer of her husband, sympathetic but also critical. (As is their youngest child, Reeve, through whose eyes we’ll often see a different perspective on her parents).” Those who helped mark Lindbergh’s way “include the pilot-poet Antoine de Saint-Exupéry and his fellow French Catholic Alexis Carrel, a Nobel-winning surgeon who balanced interests in anatomy, eugenics, and mysticism” as well as Jim Newton, “a Christian businessman who became a lifelong friend,” and a Maasai tribesman who “helped spark the aviator’s latter-day fascination with African and Pacific Island people groups that tended to find God within the wildernesses and waterways that Lindbergh worked to conserve.”

In the end, what we have in this book is a careful, experimental, and lonely Lindbergh—a largely solo flight within spiritual realms, buffeted by the realities of an exceptional life and guided by those few souls within his very small and private orbit. His daughter Reeve called it “his unutterable loneliness.” Did Lindbergh finally land in a spiritual sense? Sadly, the answer appears to be no.

Flying the spirit of Charles Lindbergh is not an easy task, but Gehrz does so with an informed grace bolstered by a historian’s expertise. What Lindbergh did for aviation, Gehrz does in this spiritual biography. The aviator charted major routes for future commercial aviation. The historian chronicles the primary paths in the pilot’s spiritual life. But the map Gehrz gives us is intentionally incomplete, like Lindbergh’s gravestone on Maui. On that stone, Lindbergh gave us one line of Psalm 139, “If I take the wings of the morning, and dwell in the uttermost parts of the sea.” Gehrz finishes the thought: “Even there shall thy hand lead me, and thy right hand shall hold me.” Charles Lindbergh extends an invitation to explore, enhance, and improve other parts of Lindbergh’s spiritual map, and to do so in the company of others.

It is a “spiritual, but not religious” biography calling for action and an “amen.”