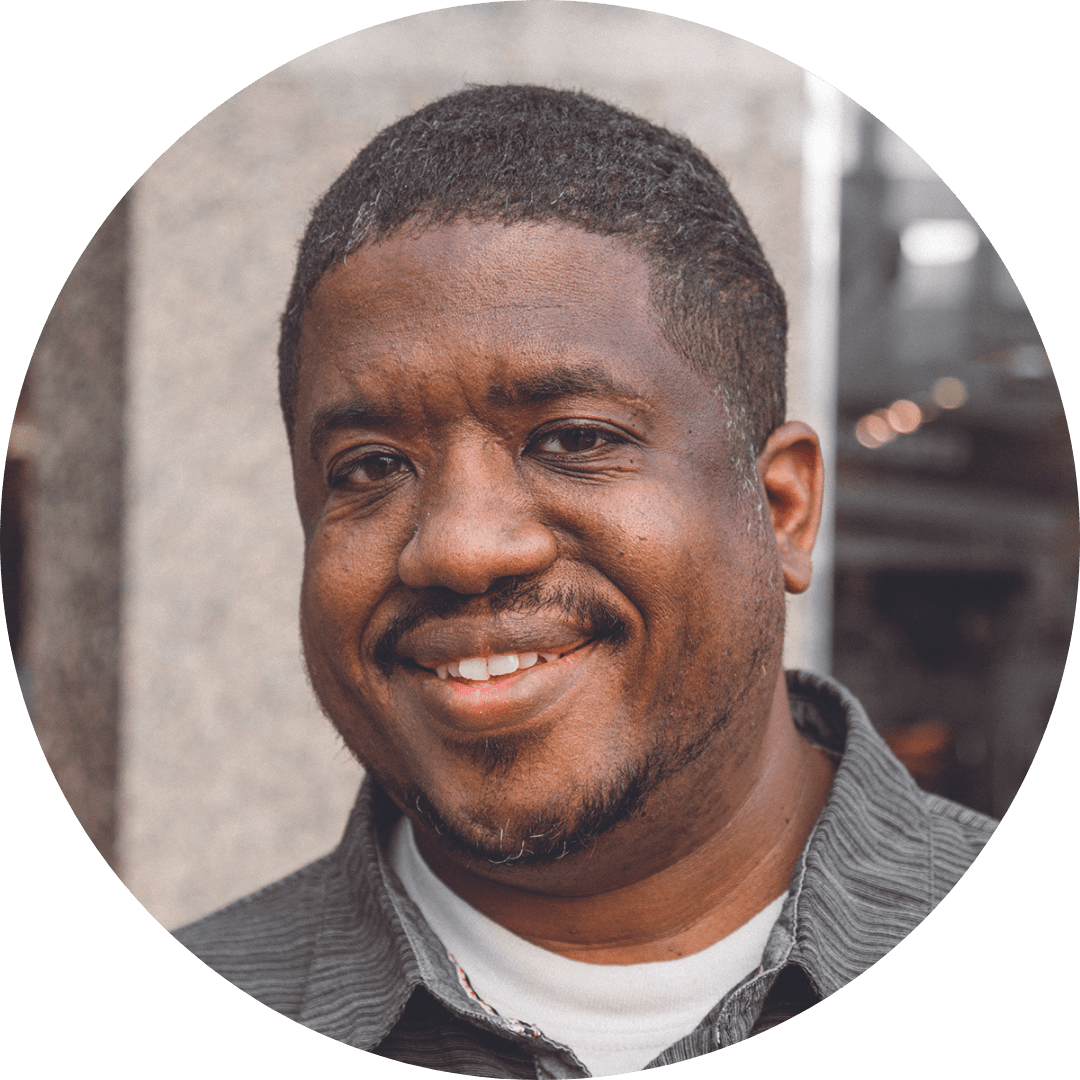

Many long-time Covenanters know him for his participation in leading worship at Covenant events or for his involvement with the African American Ministers Association (AAMA). However, semi-retired Covenant pastor Henry Greenidge also became one of the pioneers of the multiethnic church movement when he planted Irvington Covenant Church (now Portland Covenant Church) in Portland, Oregon, in 1988. For his groundbreaking leadership, he was honored by North Park Theological Seminary with an honorary doctorate in 2007, and in 2008 he received the Irving C. Lambert Award for excellence in urban ministry.

Although his youngest son, Jelani, was there for those early years, he wasn’t old enough to properly appreciate Henry’s work or impact. In honor of Black History Month, Jelani sat down virtually with his dad to talk about notable historical figures, how he found the Covenant, and what he’s learned throughout a lifetime of ministry.

Their conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Jelani: Dad, thanks for talking to me. One of my early memories of your transition into starting Irvington Covenant was your invoking the story of Abraham following God by journeying into an unknown land. Because you’re a preacher, I have a lot of memories of you mentioning biblical characters that connected to your story, but I wonder, are there any Black historical figures that you feel like your story connects to?

Henry: Thinking about Black historical figures makes me think of my upbringing. And the truth is, the influence of certain Black historical figures was blocked from me and my family.

I’m thinking about my great-uncle Richard B. Moore. He was an evangelist in Barbados at 16, a vibrant, dedicated Christian young man, part of the Christian Missionary Alliance (CMA), the tradition we grew up in. He went to Gospel Tabernacle, the big church in downtown New York off 42nd street. That was the mother church for the CMA. When he got there, they told him he couldn’t sit down on the main floor—he had to go up to the balcony. Coming from the Caribbean, he wasn’t used to that. Then he went to the YMCA, and they wouldn’t rent him a room, because he was Black.

Those experiences turned him off to Christianity, and he became focused on figures in Black history. During the Harlem Renaissance, he owned a bookstore in Harlem which was a gathering place for Black philosophers and intellectuals, and eventually, he traveled across the world. During that time, many Black folks were drawn to the Communist Party because they advocated for the rights of working people and Black freedom. So my uncle Richard joined the party because they were out there doing that work.

Uncle Richard had more than 5,000 published works in his collection, and after his death, they were eventually stored in an archive in his native Barbados. Later in life, I traveled with my brother Ralph and his daughter Joyce Turner to Barbados to petition government officials to release those works to the general public. It was a big deal; we were on the front page of the Barbados newspaper.

But before I knew any of that, what my parents said to me was, “Stay away from him, he’s a Communist.” I knew nothing about him growing up, and I didn’t meet him until I was in my late 20s. I had conjured up this idea of a rabid, angry, viscerally agitated persona, and he was nothing like that. He was a gentle old man.

JG: So Richard B. Moore was before your time, but you were also rubbing shoulders with important figures in Black history of your generation, right?

Henry: Yeah, definitely. The two others from that era are, of course, Tom Skinner and Malcolm X.

JG: I knew about Tom Skinner, of course, because you were friends. Once you asked me to introduce him at a church event before I was old enough to appreciate who he was. At the time, I sort of knew he was a big deal, but in my mind, he was just another one of my dad’s friends, so how big a deal could he be?

But wait, are you telling me you met Malcolm X?

Henry: I never met him personally, but I did hear him speak several times. When I was with the Harlem Evangelistic Association, we would be doing street meetings, and often Malcolm would be preaching on different street corners around the same time. So a few times I got to hear him speak.

What grabbed me about Malcolm was his courage, and his message of telling Black folks to be responsible for themselves, their knowledge, and their community and their children. What I’d heard from Mike Wallace and other media pundits at the time was that he was a racist, a rabble-rouser, a man who espoused violence. And Malcolm said, “I’m not an advocate of violence, I’m just saying if a man smacks me, I’m gonna smack him back.”

What grabbed me about Malcolm was his courage, and his message of telling Black folks to be responsible for themselves, their knowledge, and their community and their children. What I’d heard from Mike Wallace and other media pundits at the time was that he was a racist, a rabble-rouser, a man who espoused violence. And Malcolm said, “I’m not an advocate of violence, I’m just saying if a man smacks me, I’m gonna smack him back.”

That really helped to shape me. I was sort of a quiet, stay-in-the-background personality, and Malcolm gave me a backbone in a way that I’d never had. I mean, when he spoke, people paid attention. I have memories of watching him talk, and when I’d look around at all the high-rise apartment buildings, I’d just see all these shades going up. Everybody was paying attention. It was electric.

JG: So how did you get connected with the Covenant Church?

Henry: Well, you have to understand the context. In the CMA, there were only two Black churches in the whole city. Some of my first experiences with racism were at one of the CMA Christian camps in upstate New York. That was when I first heard certain racial slurs for the first time, and I have memories of being the only Black kid in a group full of white campers where the camp would show old National Geographic videos for entertainment, just so they could watch footage of bare-breasted African women. I remember being really ashamed and not wanting to do with anything African. At that time, even in my circle of friends, if you wanted to insult somebody you would call them African.

When I was older, I went to citywide events by Calvary Baptist, which was the leading evangelical church in the city at the time. I remember hearing a youth speaker spouting off statistics trying to prove that Blacks were intellectually inferior. I was watching that, and in the back of my mind, I’m like, I’m not sure about all this Christianity stuff.

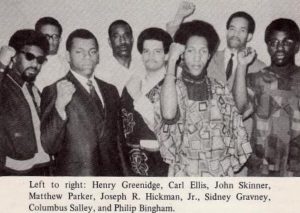

JG: A lot of that changed by your early adult years when you collaborated with Tom Skinner Associates and played in the Soul Liberation band, right?

Henry: Yeah, and a lot of that was the impetus that led me to work with Young Life, which is how our family ended up moving from New York to Seattle.

Now fast-forward to our time in Portland. I’d been on staff at Maranatha Church in Portland when our senior pastor, John Garlington, and his wife, Yvonne, passed away in a tragic car crash in Florida. Maranatha was such a significant church for the Black community of Portland that a lot of people were lining up to try to become his successor.

But I felt like God was calling me elsewhere. A friend of mine, Charlie Atkinson, who I worked with during my Young Life days, asked me, “You ever think about planting a church?” He’d just joined First Covenant in Portland.

I ended up connecting with the Covenant because of its immigrant history. There were periods in American history where you couldn’t hire Black folks, Chinese people, or Swedes. So I felt like they understood what prejudice and disadvantage were all about. Paul Larsen, when he pastored Pasadena Covenant Church in California, was outspoken in his support and advocacy of civil rights for Black people, and there were other Covenanters with him.

So eventually I got connected to Randy Roth, who was pastoring West Hills Covenant in Portland at the time, and he connected me with pastor Willie Jemison down at Oakdale Covenant on the south side of Chicago.

JG: So you planted a Covenant church because they seemed to understand the civil rights struggle?

Henry: Sort of. When Pastor Jemison brought me to Chicago to preach at his church, afterward we had a luncheon so I could share my vision for a multiethnic church. The men around the table were not optimistic.

“Alright Greenidge,” they said to me.

“That’s very nice, but let me tell you what’s gonna happen. You’ll have some white people with you for two or three years, and then one white man who thinks he knows more than you is gonna rise up and take all the white people with him. So just save yourself five years of heartache, because integrated churches don’t work.”

I said, “I understand where you’re coming from, but this isn’t Detroit or Chicago. It’s Portland, Oregon. My vision is to reach my neighbors, and my neighborhood is multiracial.”

I met with a guy from Church Growth and Evangelism (now Start and Strengthen Churches), and he tried to be nice about it, but he said, “That’s a beautiful vision, but can we encourage you? You need to narrow your focus. If you try to reach everybody, you end up reaching nobody.”

JG: So people weren’t exactly lining up to support you.

Henry: Not initially. After a while, people started coming around, but it was a process.

There was one Midwinter Conference where I had given our church’s business card to a pastor I’d just met. Our church’s logo was a heart with different light and dark-colored faces on it. And this man told me, “You got a sharp business card, but your logo is misleading.”

“Why is that?” I asked.

“Because you don’t have any white people in your church.”

JG: Had he been to your church?

Henry: No, yet here he was, essentially calling me a liar. Thankfully, before I could respond, several other pastors spoke up for me, telling him he didn’t know what he was talking about.

Eventually a few years in, our superintendent Glenn Palmberg came to speak at our church, and he was blown away by the sight of Black and white people worshiping together. He didn’t expect to see more than a few white people, but our church of around 100 people was about 50/50 Black and white. He apologized to me, not only privately but from the stage at our next conference annual meeting. “I had no frame of reference for multiethnic ministry,” he said. “I didn’t believe you because I just hadn’t seen it before.”

JG: So obviously things have changed quite a bit in the Covenant between now and then.

Henry: Back then there was no category for “multiethnic.” You were considered a Black church or a Latino church, or if you were white, you were just a church. Eventually, I connected with guys like Jim Sundholm in Minneapolis, who pastored Community Covenant Church, one of the first multiethnic churches in our denomination.

Then I started getting more active in the Worship Commission, collaborating with Paul Lessard and Rick Carlson for events like The Feast in Wisconsin and Colorado. When I led worship, for a lot of those folks it was their first time being led in worship by a Black man. For a while, before I started getting involved, Pastor Jerry Mosby from Fellowship Covenant in New York used to bring his organist to Covenant events and have him play after the main sessions were over, and we’d sort of have an after-hours type thing. Those things initiated something of a sea change in the approach to worship music at Covenant gatherings.

JG: Like a lot of career pastors, you’ve had a variety of geographical ministry experiences. What have you learned in your years traveling and ministering in all four corners of the Lower 48?

Henry: What I’m learning more and more is that racism and its fruit are more entrenched than I thought. It was providential for me to plant the first intentionally multiethnic church plant in the Pacific Northwest, because that’s a place where it was easier to thrive. It’s less rooted in many of the cultural norms—racism is there definitely, but folks are more open to the idea of operating differently.

JG: So would you say that in America we’re paying now because we didn’t want to do the hard work of reckoning with our racial past sooner?

Henry: Yeah, especially in the church. When we were living in Jackson, Mississippi, we had a young lady come to deal with the carpets in our home, and we struck up a conversation. That was one of the things that surprised me about living in the Southeast in general. I’d heard all the stories and all the history of all the terrible things that had taken place in Jackson, so I was prepared for the worst. But when I got there, everyone was so pleasant and welcoming and I thought, “Wow, this is not what I expected.”

So this lady asked me what brought me to Jackson. I told her I was helping out with a church in town that has a vision for Blacks and whites worshiping together. I told her, “Wouldn’t it be ironic if Mississippi, the place of so much cruelty and anger and hurt around issues of race, became an example of healing for our nation that set us on an entirely different course?”

All the color drained from her face. She said, “We don’t talk about those kinds of things down here,” and she packed up her stuff and left as quickly as she could.

All of this stuff today about critical race theory and January 6—it’s all staring us in the face and threatening to tear apart the dream of America.

JG: So speaking very broadly, culturally in the Pacific Northwest, they’re not so much into Christianity, but they’re open to diversity and inclusion. But it sounds like your experiences in the Bible Belt are the opposite. That lady wasn’t opposed to the church part, but she was against the whole blacks-and-whites together thing.

During the panel discussion at the end of Midwinter gathering, one of the panelists, Rev. David Holder, mentioned that he has to correct people when they assume he’s pastoring a multiethnic church. “No,” he says, “I pastor a Black church.” I don’t think he meant it as a corrective per se, but just as a way of expressing the need for ethnic-specific churches and ministries. With all the emphasis on multiethnic churches, do you think there’s still a place for mono-ethnic churches?

Henry: Absolutely, yes. I agree with David Holder, we need ethnic churches that are Black and Asian and Latino just as much as we need multiethnic churches. It’s just that for a long time, the multiethnic church was not an option. I mean, you had mostly white churches with a few Black people or other people of color in attendance, but that’s not the same thing.

JG: What else are you doing these days?

Henry: Here in Douglassville, Georgia, in addition to serving at church and playing organ with the band, I’m also part of a monthly lunch group with people of different backgrounds. There are some Black folks, a Jewish guy, a white lady who’s a Trump supporter. Even though some of us have diametrically opposed political agendas, we still gather to talk and eat together.

So I’m still a bandleader, still waving the flag for multiethnic ministry and dialogue. But I’ve switched my focus, and I’m trying to focus on the welfare and survival of Black boys with our Renaissance Leadership Academy. We’re discipling and training and trying to support the development of their brains and their opportunities to survive. We want them to be all that God created them to be.

It’s not all that different from what I did back in Portland. When I pastored for 20 years there, for the kids in our church—especially the young white kids—I was the main voice of the church for them. I like to think I imprinted something on their brains.