The Holy Invitation of A Loud and Messy Welcome

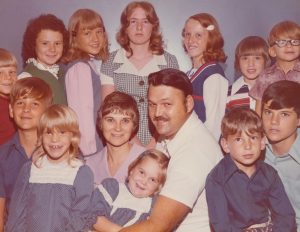

I was born into a house of welcome. On the day my parents brought me home from the hospital in Excelsior Springs, Missouri, I was welcomed by my two older brothers, Terry and Doug, and nine additional children who lived in our house. Six teenage girls and three elementary-age boys also called 1011 Miss Belle Street home because my parents fostered children. If you’ve already done the math, your calculation of 14 human beings living under one ranch-style roof would be correct. We added my little sister, Tami, to the mix four years later. The best explanation I can offer for what seems an extraordinary way of life is “welcome.”

In the late 1960s, my mom ran a residential daycare, welcoming little ones into our home each day while their parents went to work. She lost her mother at age four to an infection that followed a ruptured appendix. That loss set her on a lifelong path to care for children when their parents couldn’t. Three kids left in her care for several days were the first foster children when one became very sick and her parents could not be reached to authorize medical treatment. Child protective services said there was a shortage of foster homes and asked my parents if they’d be willing to keep the children.

In the late 1960s, my mom ran a residential daycare, welcoming little ones into our home each day while their parents went to work. She lost her mother at age four to an infection that followed a ruptured appendix. That loss set her on a lifelong path to care for children when their parents couldn’t. Three kids left in her care for several days were the first foster children when one became very sick and her parents could not be reached to authorize medical treatment. Child protective services said there was a shortage of foster homes and asked my parents if they’d be willing to keep the children.

They said yes. For the next 20 years, a caseworker would call to ask the same question: “Can you take this child into your home?” Always, the answer was yes; maybe because my mom knew this unique childhood pain of losing home and parent. But my gregarious dad also never missed an opportunity to befriend a stranger, so welcoming vulnerable kids who needed the love and care of a parent wasn’t too strange after all.

Living a Way of Otherness

I can’t even begin to unpack how those yeses shaped the trajectory of my life— so many indelible marks of gracious welcome that have informed my vocation, affected my friendships, challenged my assumptions, deepened my faith, convicted me of prejudice, and even invited me into a personal hospitality of accepting myself. Historian and theologian Amy Oden writes in her book And You Welcomed Me: A Sourcebook on Hospitality in Early Christianity: “Hospitality is not so much a singular act of welcome as it is a way, an orientation that attends to otherness, listening and learning, valuing and honoring. The hospitable one looks for God’s redemptive presence in the other, confident it is there, if one only has eyes to see and ears to hear”.

She makes two good points. First, genuine welcome has a way of orienting our whole lives toward “otherness” if we allow it. My parents certainly extended welcome when they said yes the first time to fostering three siblings. But their lives became oriented around welcome when they continued to say yes to dozens and dozens more over 20 years.

She makes two good points. First, genuine welcome has a way of orienting our whole lives toward “otherness” if we allow it. My parents certainly extended welcome when they said yes the first time to fostering three siblings. But their lives became oriented around welcome when they continued to say yes to dozens and dozens more over 20 years.

Second, when we welcome, we are confident that God’s good and redemptive presence is already at work in the person whom we don’t yet know, don’t yet understand, and with whom we don’t yet have a shared history. We demonstrate that we believe the goodness of God flows through another in how we pay attention, how we listen to them, learn from them, and value their thoughts and perspectives. One of the first to-dos, when a foster child arrived, was to get them clothes, shoes, and set up a bedroom space that was theirs. The way they attended to each child’s immediate comfort needs was a picture of God’s goodness at work before they even knew the child.

A Deeper Hospitality

The last decade for me has been a deep dive into a lived hospitality that invites people beyond the doorstep of my geographical and emotional home. I am always struck by our Western practice of keeping people on our front porch and not inviting them in. In most parts of the world, if there is a knock on the door, the guest on the threshold is invited in, offered food and drink, and all activity stops to focus on his or her presence. Sometimes the best—or even the last remaining—food resources are used in honor of guests who may or may not be a stranger.

We leave people standing on our “relational” front porch too when we keep our guard up and don’t let others truly know us. My dear friend Marshanna, who passed away in May, endured years of life-threatening health issues that often made her financially vulnerable, yet her generosity and authenticity taught me more about giving resources and self than just about anyone I’ve ever known. Looking back at leading student, worship, and connection ministries over the years, I realized that this is what my parents modeled for me too—a welcome that requires more than I sometimes think I can give. When I do invite someone into my home, my schedule, or my heart—even when my time or emotional bandwidth seems limited—it multiplies in their life and in my own.

A few years ago, I could no longer quell a restlessness that had been nagging me for almost a decade. It was part longing, part insistence that called me out of Redeemer Church where I had served for most of 25 years. All those childhood and ministry experiences were now culminating in a new way of doing church. With the love and commitment of 35 friends as well as the encouragement and support of Redeemer and the ECC, we started The Well, a dinner church here in Tulsa, Oklahoma. There is a growing movement of dinner churches across the U.S. where the shared meal becomes the central focus from which the music, conversation, and message all flow. A shared meal can be a sacred space where we welcome each person to be heard, to feel refreshed, and to find they have a place to belong at the table of faith.

This all sounds beautiful, and it is. But it is also messy and challenging. I don’t really remember experiencing quietness growing up. All those lives and stories and traumas colliding under one roof meant strong emotions, noisy dinners—and an enormous amount of laundry! It was a lot of work becoming a family under those circumstances. But there are more than 70 souls who might not have had a place to sleep or a family to belong to if my parents had not welcomed them in.

Starting a church where we invite people from an intersection of economics, ethnicities, and experiences to sit across the table from one another, listen to each other’s stories, and offer this deeper hospitality is a similar kind of challenging and messy. You cannot enter The Well and slip into the back row of a dark sanctuary unnoticed. Instead, you step across the threshold and are welcomed into a dining space or outdoor picnic where the opportunity to belong together as all our lives and stories and traumas collide.

Sometimes there are prompts on the table such as “What’s your all-time favorite movie?” or “Share your best moment from last week,” to help us move past our apparent differences and discover the fullness of “You too?” And by practicing this holy invitation, we also invite the very real, very welcoming presence of God.

If you drove past my childhood homes in Excelsior Springs or in Casper, Wyoming, your first thought might be, “There’s no way 12-14 people lived in that house!” And yet, my parents’ willingness to welcome somehow always made room for one more. It is the same posture that caused the first-generation church to explode in numbers. It wasn’t the music, a cool location, or even a great sermon. It was people always making room for one more as they gathered around food and the stories of Jesus, inviting God’s presence to join them. Practicing that kind of welcome, in my experience, has always made room for people to belong and flourish.

I like to think that The Well did not get started in March of 2020, but rather around the dinner table at 1011 Miss Belle Street in 1967.