Okay, admit it. You saw that headline and thought this was a story about the evils of Facebook as a gateway drug to online misbehavior, didn’t you? I would’ve done the same thing.

Nah, this is about a video game, and what its evolution says about culture and the future of the church. (Hang with me, I’ll get there.)

At the beginning of the pandemic, I stumbled onto a series of video games available on my Xbox all-you-can-play monthly plan. The first, Yakuza 0, was advertised as a fighting game, in the vein of such classic game franchises as Street Fighter, Mortal Kombat, or Tekken. In those games, there are cutscenes to provide narrative context to what would otherwise be meaningless combat.

So when I fired up Yakuza 0, I expected to jump right into combat and learn little chunks of the main character bit by bit, as I cleared levels, did missions, and beat bosses. Instead, I ended up watching almost eight minutes of carefully framed cinema before I ever touched the controller. In it, Kazama Kiryu, a Japanese gangster in the fictionalized city of Kamurocho, goes through the motions of enforcing on behalf of a loan shark, all while wearing a weary expression of deep ennui.

Sporting a stylish suit and deadly fists, Kiryu is known as the Dragon of Dojima. The nickname refers to a large, ornate dragon tattoo on his back, which he dramatically unveils as a menacing prelude to battle. Throughout the Yakuza series, Kiryu ascends the ranks of the Japanese mafia and then walks away from it all to rebuild his life from nothing. It turns out I had the formula backward. Instead of a fighting game with just enough story, the Yakuza games are basically hard-boiled gangster melodramas with just enough fighting to keep you from getting restless.

Playing through seven different titles in about a year’s time, I’ve grown kind of attached to Kiryu. The Yakuza series depicts him as complex and three-dimensional with traditional leading-man characteristics. He carries a deep sense of honor despite his violent, criminal career path. He’s often compelled to sacrifice his own contentedness to defend the welfare of the downtrodden and preyed-upon. He carries a deep wellspring of emotions hidden behind a hardened, laconic persona. Kiryu can lay waste to hundreds of deadly assassins at a time, but he operates with the weariness of a veteran warrior, tired of bloodshed and wondering if it’s all worth it.

It’s like God is saying, I know you’re used to that, but I want you to try this instead.

As such, Kiryu’s numerous adventures provide a window into urban Japanese culture as it existed during the production of each game. The open-world format makes it possible for the player to visit a variety of urban sectors and institutions—not just typical gangster locales like restaurants and nightclubs, but also taxi companies, children’s homes, music competitions, pro sports teams, and even fishing villages. Each story provides insight into the various problems that cities like Kamurocho face, including corporate greed, homelessness, political corruption, undocumented immigration, sex trafficking, and escalating cycles of violence. But the stories also highlight values that chart a potential way forward, like trust, loyalty, honor, perseverance, and redemption.

In the final chapter in his saga, Yakuza 6: The Song of Life, Kiryu has put down roots and sustained meaningful relationships. Even though his ending is not without heartbreak, he’s become a very different person than he was at the beginning. If there’s a takeaway to his character arc, it’s that even someone as fearsome and independent as the Dragon of Dojima still needs a family.

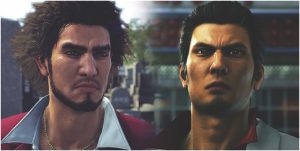

Once I finished Yakuza 6, I was pretty excited to play the next game in the series, Yakuza: Like a Dragon. Not only was it the first one to feature an English-speaking voice cast (instead of Japanese dialogue with English subtitles), but it also featured a new protagonist named Ichiban Kasuga. In many ways, Ichiban (“number one” in Japanese) is the diametric opposite of Kazuma Kiryu.

See, where Kiryu is quiet and stoic, Ichiban is gregarious and loud. Kiryu wears his hair slicked back, and Ichi’s sticks straight out, like a Japanese afro. Where Kiryu keeps his emotions bottled up, Ichi wears them proudly on his sleeve. And where Kiryu has a huge dragon tattoo on his back, Ichi’s tattoo is just as bright and vivid, but it’s a dragonfish.

They both have troubled, violent backgrounds, and they’re both expert warriors. But the changes in the leading character, along with changes in the core fighting mechanic, signal to fans that this latest installment is a departure from the norms that preceded it. No matter what similarities they may share on the surface, Ichiban is like the Dragon of Dojima, but he’s not the same guy.

And when you think about it, that “Like” in the title is doing a lot of heavy lifting. It’s promising an epic adventure worthy of the Yakuza title, but different enough to stand apart as its own kind of story. It’s saying to the player, I know you’re used to having that, but I want you to try this instead.

Now, as a Christian who came of age in the early ’90s, I’m wary of those kinds of comparisons because I know how badly they can turn out. I remember going to the music section of my local Christian bookstore and seeing charts on the wall that would identify trendy pop acts and recommend Christian alternatives, such as, “If you like Tupac, you’ll love TobyMac.” (I did eventually come to appreciate TobyMac, but that chart wasn’t doing him any favors.)

But for me, the implicit promise from SEGA’s Ryu Ga Gotoku Studio—well, it worked. Yakuza: Like a Dragon was very different, and many elements of its plot, gameplay elements, and character development took some getting used to. But the departure was a worthy journey.

In the same way, I’m looking back on the last year or so of my life since I left my last church job, my first pastoral call. I’m in a very different place now from where I thought I would be then.

There are people who say you never stop being a pastor, even if your job title is different. But I’m not so sure that’s true. I don’t think I am a pastor anymore.

But you know what? I’m like a pastor.

The original Yakuza games had Kiryu unlocking all these different moves to defeat a burgeoning phalanx of antagonists with ever-increasing intensity and difficulty. But in Like a Dragon, you start with Ichiban and learn his moves, and then as he becomes acquainted with friends, they join his party, and you all fight together. As the party swells to seven-strong, the player is introduced to moves and countermoves that escalate in intensity and ridiculousness. To beat the game, you have to mix and match their varying techniques to address the challenge at hand.

Since I started serving as worship director for Access Covenant Church in southeast Portland, I’ve noticed a similar team-based approach. Whereas in my last situation the worship service was focused around one or two people, at Access I serve on a staff of seven combined volunteers and paid staff. In our services, usually at least five different people are involved in some form of prayer, proclamation, or invitation. I get to do what I’m good at, without the pressure of having to provide in areas where I’m deficient. I get to marvel at all of the giftedness on display. Everyone is needed to accomplish the mission at hand.

It’s like God is saying, I know you’re used to that, but I want you to try this instead.

This is what I mean when I talk about being a pastor versus being like a pastor. I get into all these pastoring-type mini moments when I’m on the job as a school bus driver and I get to encourage the youth as I transport them from place to place. Or when I’m DJ-ing an event, helping to provide an atmosphere of joyful excitement or relaxation. Or when I’m engaging someone’s real dreams, concerns, and fears in an online forum. Or when I’m singing tenor and baritone in a local choir. These were all things I did in my previous role, and they helped people. I think God was honored by that work, and I like to think the people in the congregation were blessed—but it wasn’t as successful as it could or should have been. I reached a point where the role of pastor stopped being a good fit for me, but since those pastoral gifts remained, they morphed to fit my new context.

Something similar is happening in the church. We’re seeing pastoral and leadership giftedness on display in surprising new contexts. There’s a growing understanding that pastors come in different shapes, sizes, and genders. And that recognition is crucial because if you grew up with a pastor who was as stoic as Kazuma Kiryu, and then an equally gifted leader like Ichiban Kasuga comes along, you might not otherwise recognize their ability or the validity of their ministry. In pastoral leadership, we need a range of expression, skill, and technique that allows for the wide tapestry of God’s creation to come to fruition.

Besides, in the evangelical world I think perhaps we’ve put too much emphasis on the role of pastor, to the detriment of other crucial roles such as apostles, teachers, prophets, and evangelists. Maybe by decentering the pastorate as a career path—or at the very least, continuing to emphasize bi-vocational ministry positions—we can facilitate more of God’s people to be like pastors, using their pastoral gifts wherever they are called and equipped.

None of this is to say that the pastorate should be canceled or that pastors are unnecessary. Far from it. We need good pastors now more than ever. But the question remains, where do we need them most? And how can we help called and gifted women and men recognize their calling and contextualize it effectively?

I don’t have all the answers, but I know one thing: I’d rather be like a pastor, than Like a Dragon. Because full-length back tattoos? No thank you.