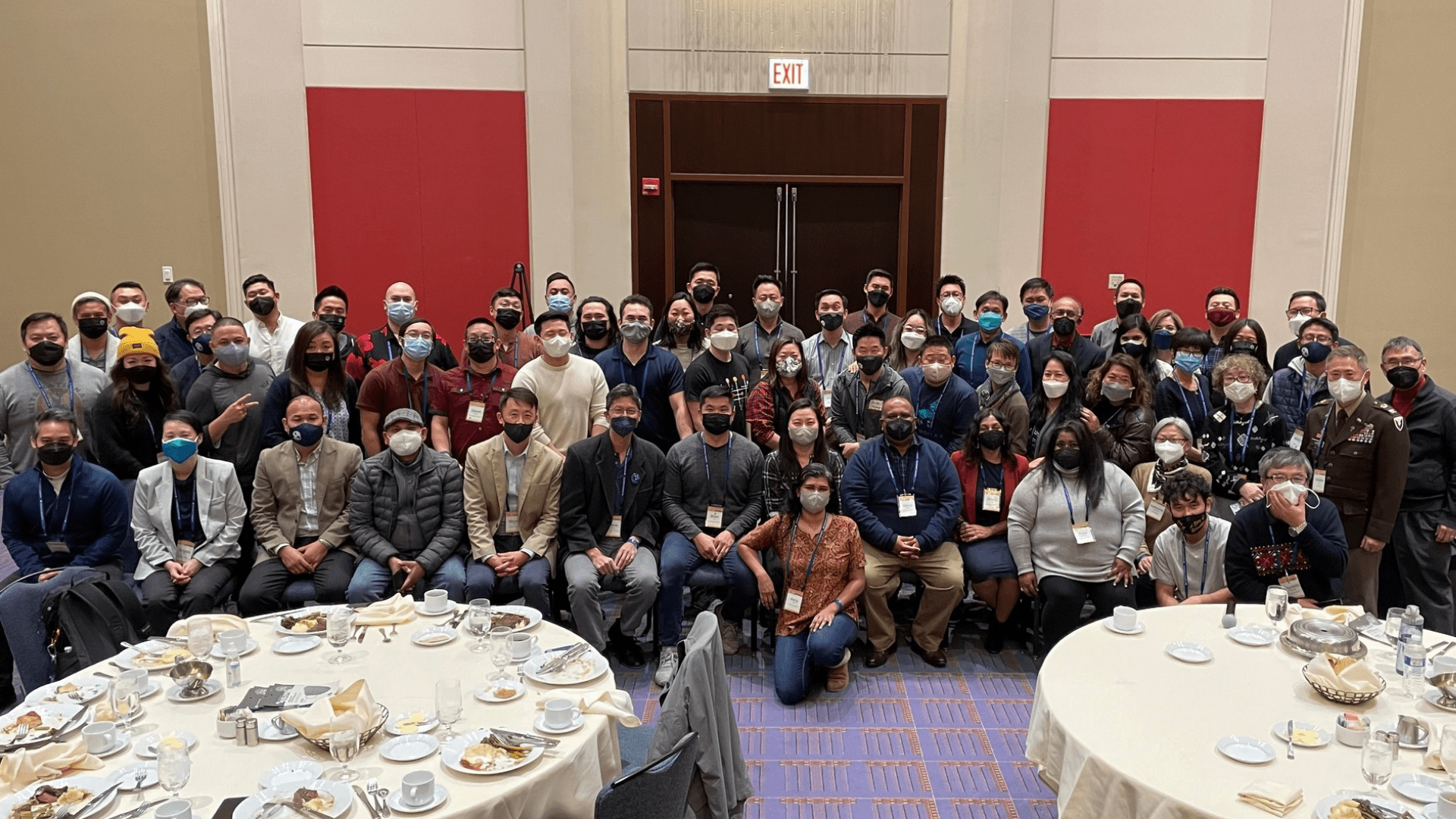

Covenant Asian Pastors Association (CAPA) at Midwinter 2022

I can’t exactly remember when it happened for the first time because it happened frequently throughout the ’90s and early 2000s. I was filling out a form for a standardized test that asked me to identify my race. I didn’t know what I was supposed to check off because nothing seemed to fit. I picked “Asian” because India is in Asia, but somehow it seemed wrong. I didn’t think I had much in common with someone from China and Japan, who were the only people I had heard referred to as Asian.

It was not my first racialized experience, but it was the first time I wrestled with the label “Asian.” In the years that followed, others would question my choice too.

I have some pride in sharing the label Asian because it connects me with incredible people, values, and history. But it is also fraught with problems. Sociologist Korie Edwards said in a recent talk that the challenge with racial categories is that they are imposed upon people based solely on external, physical factors, and they are used to draw unsupported conclusions about those people. The same problem does not exist with categories of ethnicity and culture, which are self-determined by specific groups. Race is problematic, but it is so widely normalized in our society and institutionalized in our history in the United States that we can’t help but use it.

As I navigate various church spaces, I find I have to educate people about the diversity subsumed within the label “Asian.” We see this problem even in the name “AAPI (Asian American Pacific Islander) Month.” There are many other acronyms vying for ubiquity—APIDA, AANHPI, and APAHM, for example. There are so many nations encompassed in the term Asian, but many remain obscured in these general labels.

We need to refuse to reduce our sisters and brothers to one word because no human should be defined so simply.

As we continue to explore the best way to identify ourselves in the U.S., these labels and acronyms should serve as only a starting point. This category of race reduces a vast number of languages, ethnicities, cultural groups, religious expressions, immigration stories, and histories of discrimination and prejudice into one indistinguishable mass.

While it is tempting to simply name a long list of different countries, this goes further than nationality. What many of my brothers and sisters in Christ often miss is the diversity within each nation as well. People might assume that as an Indian American, I have a lot in common with other Indian people, but those similarities are never as clear cut as they might think.

In fourth grade, I moved to a suburb from the Bronx. On my first day at a new school, they rearranged desks to seat me next to the only other Indian girl in the class, perhaps assuming we would have a lot in common. But India is home to more than 120 different languages with many more dialects, many religions, and many regional differences. My new friend (and yes, she became my good friend and remains so more than 30 years later!) had parents who immigrated from the northern part of India, while my ancestors are from the south. Her family spoke Hindi, mine spoke Malayalam, so when our parents met they communicated in English with different accents. Our traditions varied, particularly in big events like weddings. The foods she ate at family gatherings were mostly unfamiliar to me at the time. While we shared many things, we learned to avoid making assumptions about each other and to cultivate curiosity to deepen our friendship.

Even when Asian cultures share similar values, the expression of those values varies. One colleague shared a story of experiencing a misunderstanding in the practice of gift-giving when she, as a Korean American woman, visited a Vietnamese home. Because the protocol in both countries can be similar, she misinterpreted the Vietnamese family’s response to her gift. She thought they didn’t receive it because they responded in an unfamiliar way, while her actions could be interpreted in Vietnamese culture as drawing too much attention to herself as the giver.

Our immigration stories and experiences here in the United States vary widely too. Some Asian Americans have a long history here, while others have only arrived more recently. Even in the last 25 years, we witness the diversity of the Asian American experience—those who have been the focus of the recent rise of violence and AAPI hate are not usually the same Asians who were targeted for discrimination after 9/11. Even as our call to solidarity remains, we each have distinct stories and burdens that we carry and share with one another.

In a Twitter conversation on the complex diversity of the Asian experience, author Rohadi Nagassar suggests that we move our conversations toward our ethnicity whenever possible, rather than focusing on race alone. We need to refuse to reduce our sisters and brothers to one word because no human should be defined so simply.

This is the challenge and the beautiful invitation of May. In our efforts to celebrate this month, we may be tempted to inadvertently render Asians into a monolith. In people’s eagerness to participate and foster a connection, often they grab onto one aspect of our complex identities and chime in with their own personal experiences. To be Asian American is to constantly negotiate cultural and ethnic boundaries, both within our racial category and outside of it. Many times, that means dodging the assumptions of others, even in church spaces. Many Asian people find it easier to let misidentifications and oversimplifications pass.

This May, I invite my sisters and brothers to be curious. Hospitality is a strong value across Asian cultures. In our churches and communities, can we provide spiritual and emotional hospitality to host these stories? Can we make space for these stories to be heard, even when it means reaching outside of our own communities?

Navigating diverse spaces and stepping incarnationally into the world of others is a part of our call as people who follow Jesus’s example. As people of the Word, let us live into the vision of Revelation 7:9 and accept the challenge to see more clearly the beautiful complexity of the imago Dei in each of our Asian brothers and sisters.