Photo courtesy of Equal Justice Initiative/Human Pictures

The Unexpected Bonds of Kinship

My name has always been something of a challenge, particularly my first name. It is unique and is often mispronounced. (It is pronounced “Sa-nee-ta,” with a long “ˉe.”) It calls attention to itself and therefore to me, which has always made me uncomfortable.

Sanetta is not a family name. Rather, I am named after my mother’s best friend. They were childhood friends and later roommates as young single women before they married a pair of best friends. I have taken their story to mean that my family exists beyond blood. We have a history that lives through deep, chosen bonds of shared experiences, friendship, and love.

But because I have been so focused on my first name, I have often neglected to consider my last name. That unexpectedly changed when I joined the Sankofa journey in September 2019.

I could not have been more thrilled to join the cohort leaving for Sankofa. Even though I had been an African American studies major in college and had already visited many of the sites we would visit, I was excited. I believe in learning Black history and reminding the world that our story—the African American experience—is worthy to be told.

At the time of the journey, I was a year into my new role as pastor of justice, advocacy, and compassion at Metro Community Church, a Covenant congregation in Englewood, New Jersey. Founded by Peter Ahn in 2004, we are an intentionally multiethnic congregation who believes that our understanding of the gospel is incomplete without recognizing God’s heart for justice and racial righteousness and that the kingdom of God can be mirrored here on earth in the context of the church with faith and intentionality. In my role, I help the congregation understand God’s desire for a just and reconciled world as demonstrated in Scripture. I help engage our church in difficult discussions around race, faith, and the gospel. What better opportunity to grow in that role and learn than through the Covenant’s journey of racial righteousness where we visit sites of past racial injustice, seeking to look back into our history in order to move forward together?

I was grateful to have a partner in my dear friend Linda Swanson, a spiritual director who was a member of Metro and whose husband served as executive pastor at the time.

I also felt compelled to take the journey because of my deep admiration for Bryan Stevenson, a fellow Harvard Law alum who has become one of my heroes, alongside of Constance Baker Motley and Thurgood Marshall. With his fierce passion for justice, dignity, and humanity deeply rooted in his faith, Stevenson, who founded the Equal Justice Initiative, exemplifies why growing up I wanted to be a lawyer. From my upbringing in a black Baptist church who believed in the God of the Exodus and the Jesus of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to my time spent as a member of the local NAACP Youth Council, I have always believed in justice and been fascinated by the law’s ability to be an instrument for change. I wanted to be a part of that change as a civil rights attorney; however, God had other plans for me. (That’s another story.) Stevenson has built not just a law practice but is the genius mind behind the founding of the Legacy Museum and National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which opened in 2018 in Montgomery, Alabama. I was eager to visit. And so, along with other fellow pilgrims, I traveled there to learn, pay homage, and seek understanding.

Sankofa is designed to make space for pilgrims to be open and vulnerable, their hearts soft and their spirits humble. For African Americans on the journey, however, that makes us particularly vulnerable to trauma. Do you know what it feels like to anticipate pain? It’s the feeling at the doctor’s office when you see the needle coming or when you’re driving and you realize you cannot avoid that car crash. You shore yourself up to receive the blow. When we enter spaces that we know will traumatize us, we have to summon our strength and prepare ourselves to receive the impact. Knowing that, I entered into Sankofa with some caution. I was committed to the process, so I walked that fine line of faith—in fear, yet moving forward.

But nothing could have prepared me.

I walked up the path of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, holding the tension of anxiety and vulnerability in faith.

The memorial is dedicated to “the legacy of enslaved Black people, people terrorized by lynching, African Americans humiliated by racial segregation and Jim Crow, and people of color burdened with contemporary presumptions of guilt and police violence.” It begins with a sculpture immediately confronting you on slavery. The walk from the sculpture to the actual memorial is fairly long and meandering. Perhaps it’s meant to give the visitor time to prepare her heart for the experience ahead. You can’t quite see what you’re getting yourself into. I walked with Linda, taking in the expansive grounds on that beautiful sunny fall day, and stopping to read plaques and information about the memorial design and the people represented.

Awaiting me were the names of countless men and women who had been lynched in this country—my country—many with no justice meted against their perpetrators. Many had been lynched by the very people who had sworn to protect and serve their local communities but instead became murderers, destroying families and cutting off promising lives.

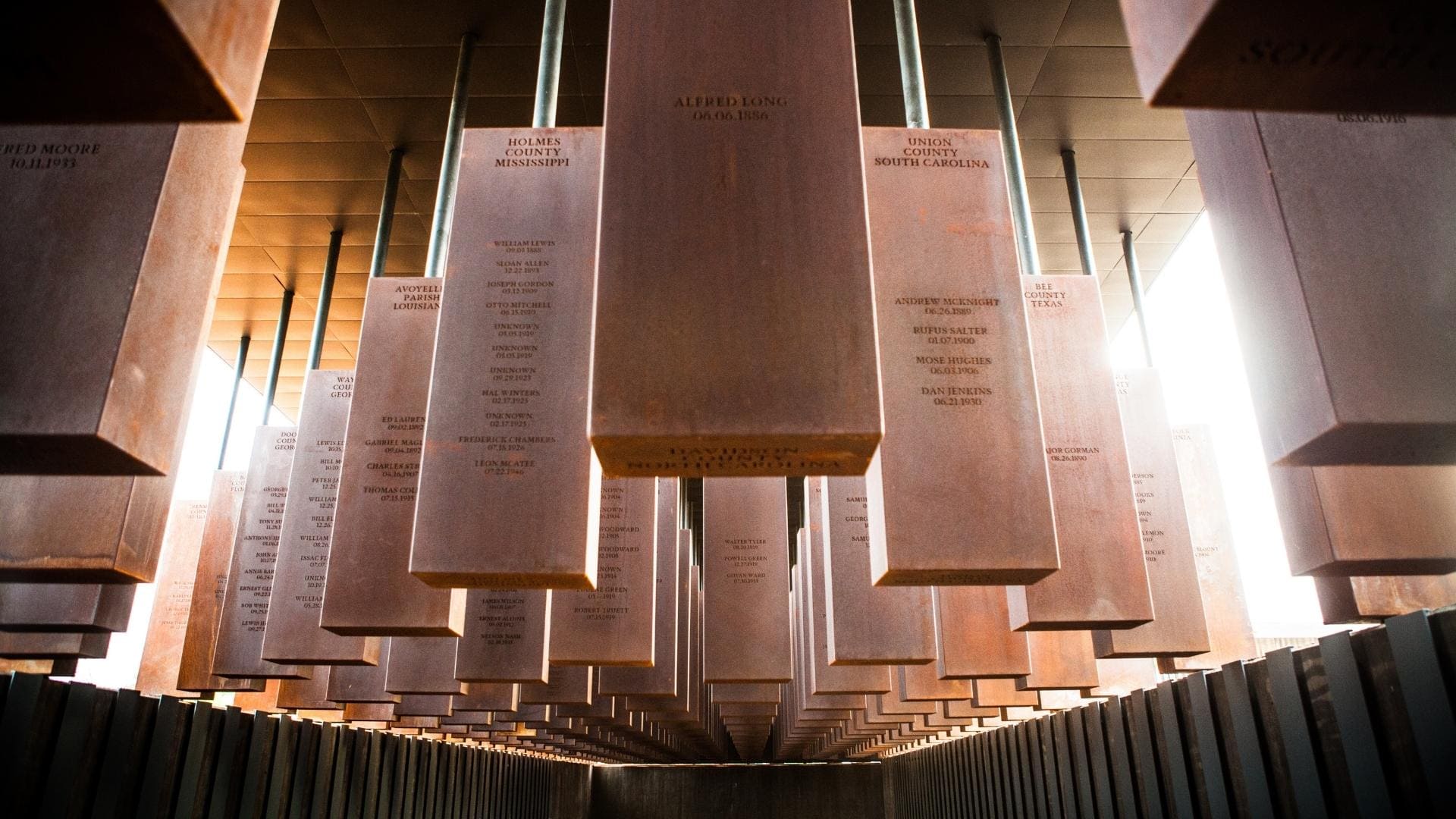

The grief in my heart was filling. Hanging steel pillars represented each county in the United States where a lynching took place. They were awe-inspiring—not in the way you might look at the Sistine Chapel, but the way one takes in wildfires raging through California or floodwaters breaking through levees in New Orleans. Except this view represented human-made disaster.

I walked, taking in names, communities, and imagining stories. My mind recalled accounts I had read that documented lynchings. So many people gone.

Curious, I made my way state by state to North Carolina. Although I was raised in New Jersey, both of my parents are from Littleton, North Carolina. As the name suggests, it’s a small town, located in Halifax County, not far from the Virginia border off of I-95. If you blink, you might miss it. So I looked for Halifax County among the steel pillars, wondering if I would recognize any family names.

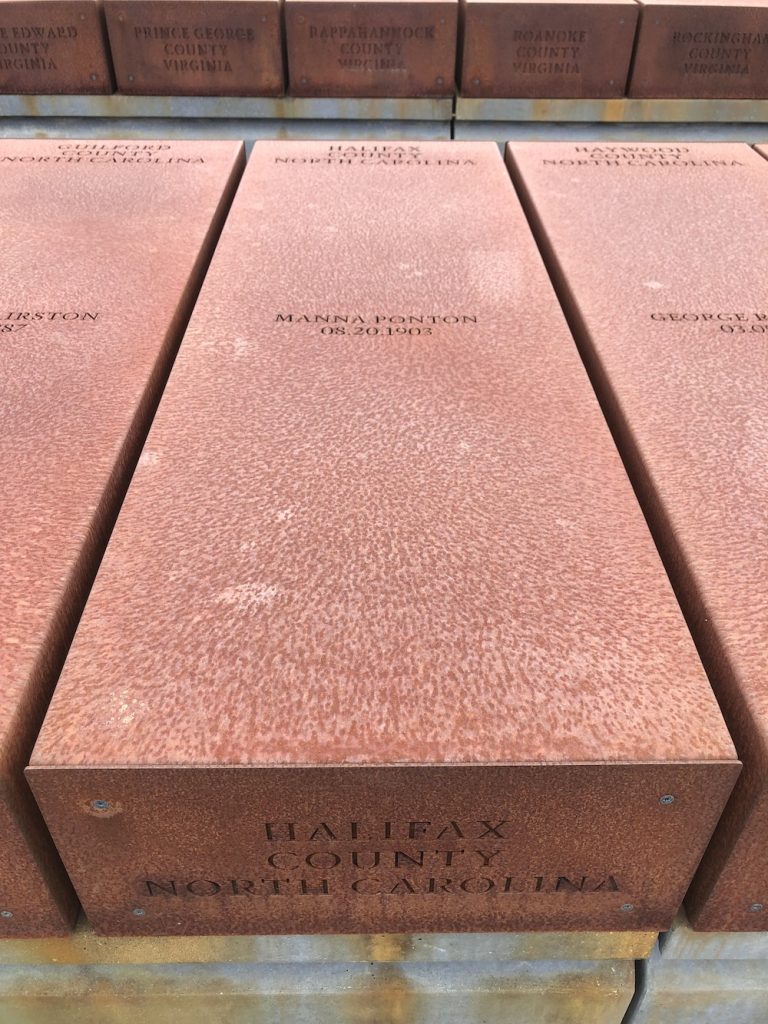

My mother’s maiden name is Williams, a name I was prepared to see. I wound my way through the pillars until finally my eyes landed on Halifax County. And there I saw a name. Just one name.

Manna Ponton.

I almost collapsed. I gasped, buckled over, and began crying hysterically. I couldn’t help myself. I couldn’t control it. I was not prepared for this!

My dear, sweet partner, Linda, turned around and in the same motion read the name and grabbed me. She and a staff member of the memorial took me to a ledge where I could sit down. I was shaking. I couldn’t breathe. All I could do was cry. I was crying deep sobs from a place only my ancestors knew. Heaving. My name was on that pillar—PONTON! No book had prepared me for this. No lesson studied could make sense of it. No hymn, no Scripture. A part of me was dead. I didn’t know the story and I didn’t need to. Ponton had been lynched.

Linda told me later that was the first time she had seen anything literally take someone’s breath away. She said I stopped breathing. The gasp was audible. My name was on that pillar.

I had been prepared for the common name of Williams. Its familiarity offered a measure of distance between me and someone else with that name. I have met countless people with the last name Williams who have no relation to me at all. Seeing that name would have been like reading a list of names in a book—a Williams, but not necessarily one belonging to me.

But Ponton? The name is so uncommon that people wonder how to pronounce it (Pon-ton). They wonder from where it derives. (Is it French? Perhaps.) All I know is that my father is from Halifax County in North Carolina. And so was Manna Ponton. But Manna Ponton was lynched.

It’s a strange feeling to mourn for someone you’ve never met and yet feel a deep kinship toward. Who was he? How did he live? What were his dreams? What were his gifts? Whom did he love? Who loved him? Why was he murdered?

And yet, at that moment (and even still now) none of that mattered. He was a part of me. And he was lynched.

After returning from Sankofa, I began by asking family about him. My father didn’t recognize the name. Neither did any of my aunts. My grandparents are deceased. I looked for his name on the internet, hoping to find a newspaper article or story.

From what I can gather, we are probably not physically related. Chances are, our families descend from the same plantation where our ancestors were held enslaved by the Ponton family. History tells us that enslaved people were given the name of those who held them captive. Not related but our bloodlines share a history revealed by a name. Slavery. Violence. Terror. In his name is my father and my brother. In his name are generations lost and dreams left unfulfilled. In his name is anger and rage and heartbreak and sorrow and confusion and loss and a grief I did not know I could feel for someone I’ve never known. In his name is me.

My heart breaks for a man I have never met. Indeed, my soul is filled with grief for a man I will never meet. I want him back, even though I never knew him. And yet in some strange way, I do know him. He is a Ponton. For me, that means in his name is also love. This is a love that spans generations and time. It recognizes kinship and belonging. He is a part of me. And he was lynched.

There are no words for this kind of pain. There is no book or TED Talk on overcoming the grief of murder by lynching. Do the stages of grief still apply? Where do I hold the rage? What contains the sorrow? It seems to live in my tears, in my activism, and in my passion for justice. Sometimes it feels like too heavy a burden to bear. Is this what Jesus felt when he overturned the tables of the moneychangers and drove them out of the temple with whips? Is it what he felt when he cried over Jerusalem or at the tomb of Lazarus? Is this the horror of that Saturday between Good Friday and early Easter morning?

Now I realize that at the moment I came face to face with the murder of Manna Ponton, something died in me too. The desire to try to understand racism is gone. It’s evil. Period. The desire to make history easy and palatable for others is gone. It happened. Face it. I had always fought for justice. I had always been keenly aware of the sick atrocities perpetrated against people of color in this country. But I had always sought to temper my anger with a false grace rooted in an unconscious belief that my anger (perhaps because I am a woman or African American or a “good Christian”) could not be rightfully expressed. That’s gone.

Today, instead of tempering my anger, I allow the imprecatory psalms to speak to me. And I talk back—for me, for Manna Ponton, and for all who bear my name. The Scriptures make space for anger and rage. Why shouldn’t we?

I know the resurrection is coming, but sometimes I sit in the pain of the in-between because Manna Ponton was lynched. A man bearing my name was lynched. Here is where I choose to honor my name.