Juneteenth is a celebration of the abolishment of slavery in the United States. Columnist Jelani Greenidge takes some time to explain what it is, how it came to be, and how it’s celebrated.

(transcript from video above.)

Juneteenth! It’s a portmanteau of the words “June” and “nineteenth,” which is a fancy way of saying that’s what you get when you smoosh those two words together. Juneteenth is now a federal holiday, so this is me taking some time to explain what it is, how it came to be, and how it’s celebrated.

So let’s start with the history.

HISTORY

Juneteenth is a celebration of the abolishment of slavery in the United States. Specifically, it commemorates the anniversary of June 19, 1865, when Union General Gordon Granger arrived at Ashton Villa in the coastal city of Galveston to issue General Order No. 3, which freed all formerly enslaved people in the state of Texas.

Now if you’re like me and not much of a historian, you might be wondering why all of this was necessary. Wasn’t the war already over by that point? And weren’t all the slaves already free after the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation by President Abraham Lincoln? And isn’t this why the war ended, why President Lincoln is such a pivotal historical figure, and why Black History Month is in February because that’s the month of Lincoln’s birthday?

And the answers are, in order, yes, no, not exactly, yeah sorta, and calm down I’ll get back to you about that in February.

See, June 19, 1865, was more than two years after President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, and it was more than a month after the official end of the Civil War, which formally ended after President Johnson—no, not LBJ, the other president Johnson—issued an executive order on May 9 of that year.

Why the delay? Well because General Order No. 3 was essentially an order of enforcement. Although slavery had already been officially outlawed, it took more than two years for the southern rebellion in Confederate states like Texas to collapse and provide an opening for the official U.S. Army, a.k.a. Union troops, to slide in and start making local landowners obey the law.

So Juneteenth represents more than just a formalized notice of victory over the Confederacy, but an actual declaration of freedom on the ground. Juneteenth celebrations often involve parades in order to recall the memory of General Granger’s soldiers who marched throughout various locations in Galveston to inform the populace that all the slaves had been freed. For Black Texans who’d grown up under the brutal oppression of slavery, the announcement ignited an explosion of rejoicing, because the theoretical good news of way over in Washington was suddenly good news right here and now.

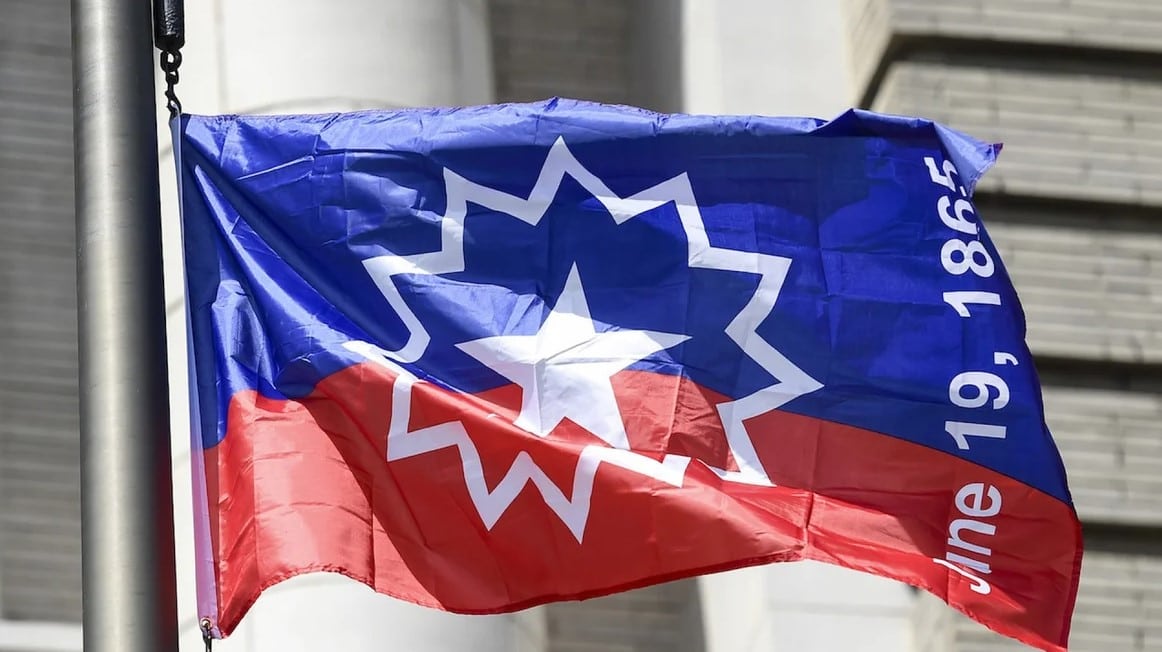

Now because of its geographic origin, Texas became the first state to recognize Juneteenth as a state holiday in 1980, but for decades Juneteenth has been an informal holiday for generations of African Americans, particularly in the south. In 1997, an African American community activist out of Boston named Ben Haith designed the Juneteenth flag and later founded the National Juneteenth Celebration Foundation. That foundation, now based in DC, alongside several other similar Juneteenth-themed civic groups around the United States, continually generated momentum and recognition for the holiday, which had been gradually adopted by dozens of states during the 2000s and 2010s, until it was officially signed by President Biden as a federal holiday on June 17, 2021.

HERITAGE

Now even though Juneteenth was recently established as a federal holiday, celebrations like Juneteenth are more than just political theater. As followers of Jesus, they’re part of our spiritual heritage. Both the longing for freedom and the celebration of its arrival are circular rhythms with echoes of the Jewish Passover feast, where the children of Israel remembered God’s deliverance from the hand of the Egyptian pharaoh. All throughout the Old Testament, we see story after story of God’s faithfulness to God’s covenant people, who often experienced victory and deliverance against formidable odds. In truth, many of the idioms and much of the language from the American Civil Rights Movement invoke those Old Testament texts, the struggles of God’s people as they sojourned through time, facing not only military pressure from neighboring armies but eventually exile and oppression from foreign occupation.

So while Juneteenth is not a sacrament on the liturgical calendar, it does represent an opportunity for us as a church to raise an Ebenezer, a tangible sign of God’s miraculous providence as we’ve experienced it thus far. As the lyrics of “Amazing Grace” remind us, “through many dangers, toils and snares, we have already come.”

Not only that, but the Juneteenth historical narrative is consistent with a theology of God’s kingdom described by Princeton theologian Gerhardus Vos as the “already but not yet.” On that fateful day, the Black residents of Galveston Texas were encouraged to embrace the freedom for which they were already legally entitled but hadn’t yet opportunity to experience. Because of the authority of the U.S. government, they were no longer slaves, but now citizens.

In the same way, we as the body of Christ embrace communal practices that recognize the authority and power of God’s upside-down kingdom, even as we anticipate the full revelation and manifestation of God’s kingdom yet to come. As Paul instructed Philemon about his former employee Onesimus, we are exhorted to treat one another not simply as employees or slaves as the world would view us, but as sisters and brothers of a royal family.

Therefore, just as Paul’s mission extended the gospel of Jesus to the Gentiles as well as the Jews, we as African Americans and believers in Jesus offer up our cultural celebration of Juneteenth as a narrative of freedom for everyone to experience.

Likewise, for Christians of other ethnic or cultural backgrounds, Juneteenth represents an opportunity to follow the Apostle Paul’s admonition to the Romans. Just as we practice solidarity during times of tragedy by mourning with those who mourn, we’re also instructed to rejoice with those who rejoice. And more than a theological reflection, political event or a historical observance, Juneteenth is first and foremost, a celebration.

THE COOKOUT

Now because Juneteenth is an established holiday, many different cities and communities around the U.S. have established, or are establishing their own official observances, festivals, parades, block parties, et cetera.

But just as often, Juneteenth is honored in a less formal context. ‘Cause when it comes to Black folks in celebration, there’s nothing like a good old-fashioned cookout. During the hot summer months, Black people across America gather in outdoor spaces to enjoy good music, raucous conversation, and a bounty of delicious barbecue.

But it’s more than just those things by themselves. There’s an ineffable quality to the cookout, a tremendous, celebratory vibe that’s difficult to pin down with words. If you took all the joyful celebration of a traditional Black church, but moved the whole thing outside, let everybody dress down a little bit, and then invited all the crazy aunties, uncles, and cousins who don’t know how to behave in church—that’s the cookout. If you ever saw somebody’s grandparents show off the dancing moves they perfected in high school, it probably happened at the cookout. If you ever witnessed two people almost come to blows after talkin’ trash over a game of spades or dominos, it probably happened at the cookout. If you ever gave or received a compliment about the ribs or the mac-and-cheese that involved phrases like “girl you put your foot it” or “chile, this so good it make you wanna slap yo momma,” * it almost certainly happened at the cookout.

It’s like a potluck, a community forum, and a family reunion all rolled into one.

In one way, the cookout is one of the most American of traditions, because it’s an implicit celebration of our place in the community. Having looked back at all of the troubles and trials we’ve endured, we gather in gratitude, celebrating the fact that we’re still here. As Dr. King alluded, we consider all the unclaimed resources in the American promissory note, and we rally ourselves, our friends, and our family to keep keepin’ on, no matter what, refusing to accept “non-sufficient funds” as an acceptable answer.

At the same time, however, the cookout is such a quintessential part of the Black experience that it has become the dominant 21st-century metaphor for Black culture writ large, especially online. When Black folks on Twitter talk about how to behave, it’s often referred to as etiquette for the cookout. When White folks show visible and meaningful signs of support and solidarity with Black people and Black causes, we often jokingly refer to them as having earned an invitation to the cookout.

The cookout is a place where the sinners come to Jesus, the saints come to celebrate, and everybody can come get a plate. Where you can be heartily affirmed for your heartful prayer asking God to bless the potato salad, and mercilessly roasted for putting the wrong ingredient in that very same potato salad.

It’s one of a few spaces that are completely and unashamedly Black, where we can be fed, and be family.

THE MUSIC

And the only thing besides the food that can make or break a cookout is the music. Black music is the lifeblood of Black culture, as it is with so many different cultures. A cookout with no music is like a meal with no seasoning—it’s just wrong.

So whether it comes from live performers on a festive stage, a DJ with speakers and subwoofers, a simple Bluetooth speaker, or an 8-track cassette player in a drop-top Cadillac, somebody gotta be playing some kind of music, or it just ain’t a proper cookout.

Now, the thing about a Juneteenth cookout playlist is that it needs to help generate the right community atmosphere. There should be tunes in multiple styles that touch on the heyday of multiple generations. I’m talking about R&B, funk, jazz, hip-hop, and yeah, even some gospel. A great cookout playlist should be one where most people know at least half of the songs, and everybody has at least one or two moments where a song comes and they say “ayo turn it up, that’s my JAM right there.”

Since Juneteenth is a summertime celebration of freedom, I’ve put together a DJ mix of decade-spanning, cross-generational Black music, some sacred, some secular, and you can find the link in the description. And if you want an even deeper dive on the spiritual and historical significance of Juneteenth, check out this 75-minute documentary from Our Daily Bread Media featuring Pastor Rasool Berry, with original hip-hop from Sho Baraka.

So if you live in the U.S., then wherever you happen to be this Juneteenth, I hope you have a chance to crank up the jams, connect with friends and family, and enjoy the vibe. And while you’re at it, take a moment to be thankful for how far we’ve come as a nation, and consider what role you might play in helping the United States of America become more just, equitable, and of course—free.

* This expression is a term of affection generally used between Black women and should be avoided by others, especially White adults or Black children.