100 Years of Covenant Children’s Ministry

With $3,616 in the bank and a heart-felt vision for helping children, a group of early Covenanters began working on plans for a ministry that would help children whose families were in distress.

The idea for a children’s home had first been raised at a Sunday school conference in 1917. Since then, a group of volunteers had been hard at work raising funds. Now it was time to put those funds to work.

Before long, a house and six acres of land had been purchased by a committee of Covenanters appointed by the central conference, and work on starting the Covenant Children’s Home of Princeton, Illinois, was underway. The home expanded to include several buildings, a farm, even a gymnasium—and a number of children came to live there, especially after the stock market crashed in 1929.

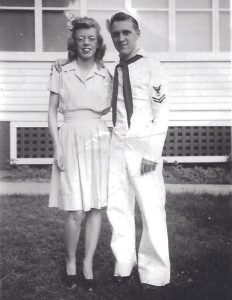

Among those children were Ray Vetter and Ruth Olson.

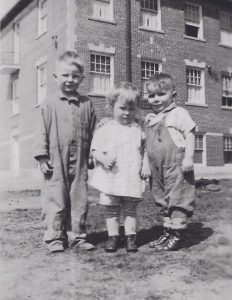

Vetter was raised in Chicago and for a while worked as a newspaper boy at a stand near Wrigley Field. Then his mother died, and his father lost his job and could no longer care for the family. Three of Ray’s siblings were taken in by families in their church. Ray and two other siblings came to the children’s home.

Olson’s family had also experienced tragedy. Her parents had served as missionaries in China, then settled in Iowa, where Olson was born. Her parents also had six kids and had made their way to Chicago before her mother died and her dad lost his job. Ruth too ended up at the home. She met Vetter there when they were both teenagers.

“They both say it was like having a family–with a lot of brothers and sisters,” says Debby Vetter, daughter of Ruth and Ray, who married after they graduated from high school.

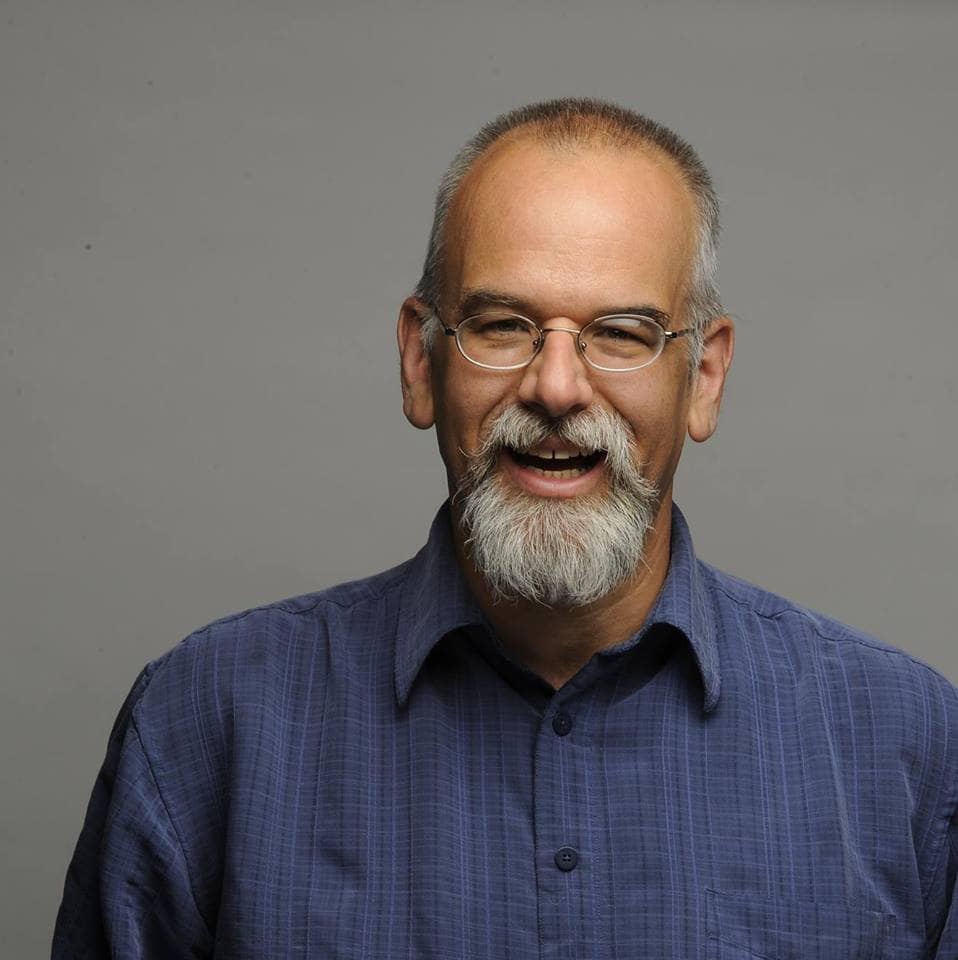

This summer Ray and Debby, who both still live near Princeton, will be back at the site of the children’s home for the 100th anniversary of its founding. The two will help open a time capsule as part of the celebration, which will recall the past ministry of the children’s home and look forward to the future.

“We want to celebrate what God has done over the past 100 years,” said Paul Bengtson, a retired Covenant minister serving on the committee planning the anniversary.

The children’s home in Princeton played a prominent role in the Covenant’s history of caring for children and families in need. That history dates back at least to 1883 when Henry Palmblad was hired by Covenant churches in Chicago to help struggling Scandinavian immigrant families. Palmblad, who was a foster parent, went on to found a Home of Mercy in the 1800s, whose first residents included several young children, according to a 2001 Companion article. In the early 1900s, a group of Covenanters on the East Coast also founded a children’s home in Cromwell, Connecticut, to care for orphans and children from struggling families.

While the Covenant’s ministry to children has been reshaped over the past 100 years—orphanages were replaced by homes for youth who were struggling and later programs to assist at-risk children and their families—the focus of Covenant ministries has remained the same, says Harold Spooner, a long-time board member of Covenant Children’s Ministries (CCM). Covenanters, Spooner said, have always been committed to “God’s glory and our neighbor’s good.” CCM is now one of several ministries overseen by Covenant Initiatives for Care, which is part of Covenant Ministries of Benevolence.

Bengtson has long had ties to the Covenant’s work in Princeton. He served as a chaplain at the Covenant Children’s Home from 1989 to 1997, then in 2011 joined the CCM board for a decade, after returning to Princeton to be closer to his grandchildren.

When Bengtson was chaplain, the Children’s Home had nearly 200 employees and a $5 million annual budget, according to an online history of the ministry. At the time, the home had evolved from its beginning as an orphanage to a residential treatment center for children with emotional difficulties, who had often grown up in difficult family settings. That work was funded in large part by the State of Illinois.

By 2000, the residential program was no longer financially viable and shut down. But the ministry at the Princeton campus did not stop. Renamed “Covenant Children’s Ministries,” the Princeton campus became home to several nonprofits that served children and families in the community.

That property is now in the process of being sold. Some of it was bought by the nonprofits who had rented space there, including Freedom House, a domestic violence shelter, and Braveheart, a program that serves at-risk children in Princeton and other communities.

Proceeds from the sale are being used to fund ministries that serve at-risk children both in Princeton and in Covenant churches around the country. Among the ministries CCM has helped support in recent years are church-based programs in the Central Conference as well as Alaska Christian College and the Amundsen Educational Center, two faith-based schools in Soldotna, Alaska.

In the past, the board has focused on funding projects on an ongoing basis. With more funds, they hope to expand that work and give larger grants that would be transformative, said Bengtson.

Spooner, who served as vice president of community impact for Covenant Retirement Communities and president of Covenant Initiatives for Care, said that since 2012, CCM has given away more than $2 million in grants. With the sale of the Princeton property, CCM hopes to aim bigger. They hope to help churches partner with nonprofits, local governments, and communities to “do something systematic in their neighborhoods to mitigate the risk factors for children and young adults,” said Spooner.

Ädelbrook Behavioral and Developmental Services, a ministry of Covenant Ministries of Benevolence, in Cromwell, Connecticut, serving at-risk kids and their families, can serve as a model. Founded as the Swedish Christian Orphanage in 1900 and later known as the Children’s Home of Cromwell, Ädelbrook now operates several learning centers, in-home services for at risk-kids, residential programs, and other services, funded by donations from Covenanters and other supporters as well as government funds.

Addressing those complex needs requires significant resources, said Spooner. That means churches and other faith-based groups need to work closely with public and nonprofit partners. “We are going to have to work with them if we want to make significant progress,” he said.

Debby Vetter said her father, who is 101 and still lives on his own, has fond memories of the children’s home. As a kid, he helped milk cows and worked in the garden when he was not at school, while Ruth and other girls washed dishes and darned socks. “My dad also peeled a lot of potatoes,” Vetter said.

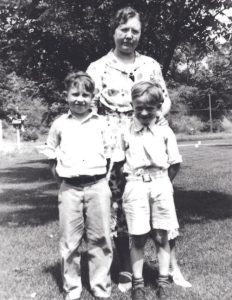

Vetter said her dad gives credit to Bertha Nelson, who ran the children’s home for much of his childhood. Nelson and her husband, Rev. Gust Nelson, were appointed to lead the home in 1923 and under their stewardship, expanded the home, put in a central heating plant, added a barn for the farm, and raised funds for a gym. After Gust died, Bertha served as the matron of the children’s home until 1940.

Vetter said her parents later became foster parents themselves. They never forgot the kindness they had been shown at the children’s home. “They were always doing something for other people,” she said.