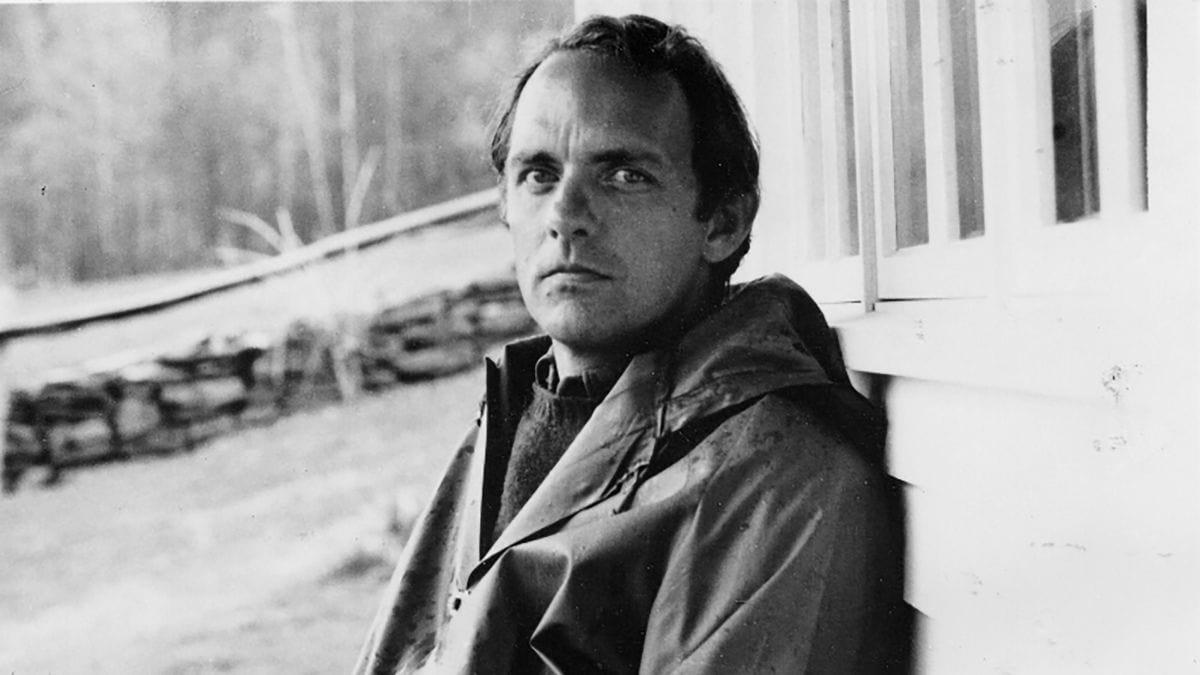

Once upon a time, Fredrick Buechner upended everything I believed.

He was the first author to do that to me. His death last week prompted me to reflect on a weekend years ago when Telling the Truth: The Gospel as Tragedy, Comedy, and Fairy Tale wrecked my faith.

Buechner had been a visiting professor at my Christian college, but I’d never heard of him and failed to sign up for his course when he was on campus. As a diligent evangelical, I preferred didactic writers, preachers, and Moody Bible Institute’s radio station. I memorized Romans 6 on a summer mission trip (“What shall we say then? Shall we continue in sin that faith may increase? May it never be!”) with an organization that taught me that emotions are the caboose of our faith, and our rational mind is the engine that drives the train. When I did read fiction, it was just for fun. I didn’t know you could find God in story.

Then one sweltering weekend, my best friend came to visit my apartment in Chicago. Somehow our casual conversations about our young adult lives turned into a two-day crash course on Frederick Buechner. We holed up in my stifling, un-airconditioned studio and read Telling the Truth.

The first part of the title seemed clear to me. “The Gospel is bad news before it is good news. It is the news that man [sic] is a sinner, to use that old word, that he is evil in the imagination of his heart, that when he looks in the mirror all in a lather what he sees is at least eight parts chicken, phony, slob. That is the tragedy.”

Yup. That sounded about right.

But comedy? Fairy tale? Those words were anathema. The Gospel, I knew, is truth, not make-believe.

So at first, Beth and I argued. I probably said words like “absolute truth.” She was dismantling all my understandings. It was scary. What if all my devout certainty collapsed? What would I be left with?

But gradually I began to glimpse a deeper, holy truth in Buechner’s words.

“Is it possible, I wonder, to say that it is only when you hear the Gospel as a wild and marvelous joke that you really hear it at all? Heard as anything else, the Gospel is the church’s thing, the preacher’s thing, the lecturer’s thing. Heard as a joke—high and unbidden and ringing with laughter—it can only be God’s thing.”

He talked about the Gospel as the fairy tale that is too good not to be true. “It is not Disney Land where everything is kept spotless and all the garbage is trundled away through underground passages beneath the sunny streets. On the contrary, the world where this Joy happens is as full of darkness as our own world, and that is why when it happens it is as poignant as grief and can bring tears to our eyes.”

Our hours of discussion were exhausting and invigorating. By Monday morning I was reconsidering everything I thought I knew.

I went on to read everything I could find by Buechner. His language helped me enter into new stories. His memoirs were raw and honest. His theology was grace-filled. I struggled with his fiction, with his portrayals of holy men (yeah, they were men) who were broken, flawed, and in my view unlikable. Today, though, I can better see their humanity. I have learned more about human complexity—that each of us is both good and broken. That we reflect the imago Dei and the Fall of humankind, sometimes in the same moment. Perhaps I am still being changed by Buechner’s writing.

As my individualistic faith expanded, I moved on to other authors who wrote about systems and communities, about women, about justice. Today, some of Buechner’s language can be tone deaf and insensitive. Yet he remained a trusted companion in the background of my journey after playing such a pivotal role in my young life.

One passage from Telling the Truth has lingered in the back of my mind every time I have listened to a sermon in all these years.

“The preacher pulls the little cord that turns on the lectern light and deals out his note cards like a riverboat gambler. The stakes have never been higher. Two minutes from now he may have lost his listeners completely to their own thoughts, but at this minute he has them in the palm of his hand. The silence in the shabby church is deafening because everybody is listening to it. Everybody is listening including even himself. Everybody knows the kind of things he has told them before and not told them, but who knows what this time, out of the silence he will tell them?”

That holds for the storytelling each of us does as well. For a moment, we all pause with anticipation, listening. Will we tell the truth?