How the story of Joseph helps me find peace in spaces of trauma-filled waiting.

If your church is anything like the ones I’ve served, it is almost certain that someone struggles to light the candle on the Advent wreath on the first try. No matter how much we check the lighter fluid beforehand, we always experience at least one fail. The serene moment of reflection becomes filled with anxious laughter as the reader desperately tries to light the wick.

As we reflect on the coming birth of the Messiah, the waiting period is often anything but serene and perfect. It is often filled with anxiety, trauma, and disappointment. The reality is that even though what is promised is amazing, the waiting isn’t.

Our Advent waiting centers around the Savior that was promised, the Savior that was prophesied, the Savior who would come to deliver us. Churches adorn their sanctuaries with tapestries, lights, garlands, trees, and of course the Advent wreath. Each Sunday someone from the congregation comes forward to light the candles that represent hope, peace, joy, love, and finally the Christ candle. It’s a beautiful tradition. What we don’t do as often is consider the weight of the wait—the heaviness that comes with waiting for the promise to be fulfilled.

We live in a society that works diligently to reduce waiting times. The conventional oven is replaced with the microwave, and now air fryers have revolutionized the cooking process again. We’ve gone from manually turning the television dial to being able to speak to devices to change channels or streaming platforms instantly. We abhor waiting. Yet as believers, we are called to prepare and wait for the thing we desire most—the return of the Savior, the fulfillment of the promise.

We don’t usually read the story of Joseph in Genesis during Advent, but it can serve as a foreshadowing of what it means to wait for a promise to be fulfilled.

In Genesis 37, Joseph receives favor from his father—just because. This favor is represented by a regally adorned cloak, the cloak that pits him against his brothers. In that chapter, the one who grants favor shifts from his earthly father, Jacob, to his heavenly Father when God shows him a vision of his future. Joseph eagerly shares this dream with his family—which only increases the divide between him and his brothers. We know what happens next: His brothers sell him into slavery.

But even in captivity, Joseph finds favor and begins to serve Potiphar. Then he is sexually assaulted by Potiphar’s wife, falsely accused of assault, and imprisoned. He finds favor in prison, but after helping interpret the dreams of fellow prisoners, he is seemingly left to rot.

It takes another two years for Joseph to be brought before Pharaoh and put in charge of the kingdom. That means it was essentially 13 years after he received the vision from God before he even began to glimpse the future God had promised. Joseph endured trauma after trauma while waiting for that promise to be fulfilled.

Today in the church we celebrate the coming of the Messiah, even while anxiously waiting for his return. We too are dealing with a millennium of trauma. Wars, genocide, slavery, poverty, disunity, and more things than I can name!

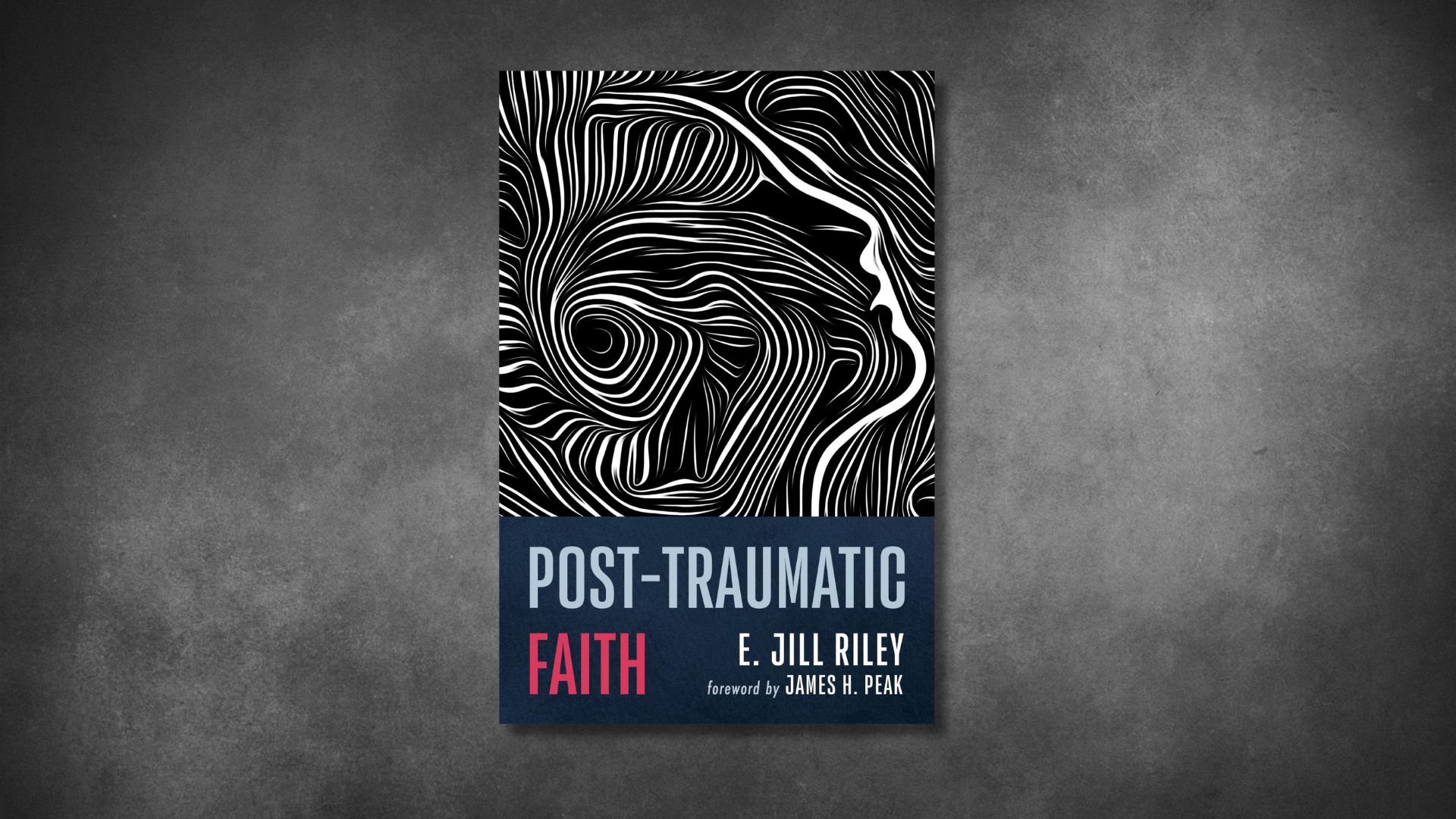

Reflecting on the life of Joseph in this season has given me a new perspective on what it means to wait. Our culture often avoids conversation about trauma, encouraging people instead to persevere through it, without taking time to heal. In our churches, we often avoid hard conversations in name of peace. I think this has the adverse effect of making us ill-equipped to deal with disappointment as we wait for the promise to be fulfilled. Joseph’s story has helped me be comfortable with the beauty of waiting, while at the same time grappling with the weight of the wait. Yes, Joseph was eventually able to profess, “What you meant for evil, God used for good.” However, there was a lot of trauma-filled waiting in-between the promise and that proclamation.

My prayer this season is that like Joseph, we may remain faithful in the waiting, without ignoring the difficulties we face. If we allow ourselves to feel that weight, maybe we will experience the coming triumph more fully. Like Joseph, may we see that not only does God use pain and trauma to lead us to triumph, but that he is with us all along.