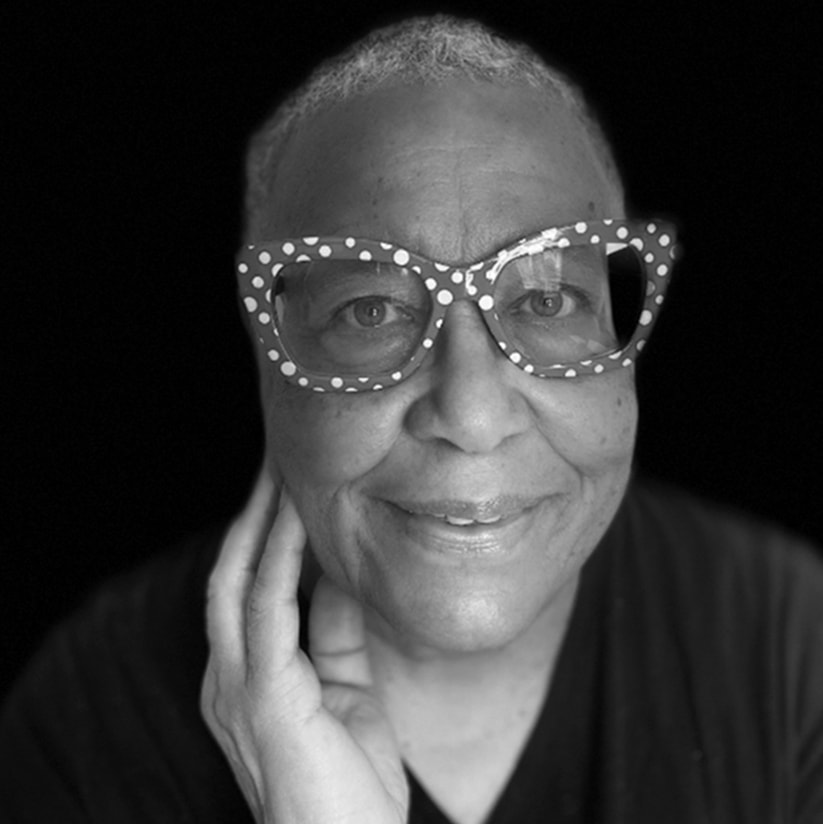

I was 65 years old when I was commissioned at the 124th Annual Meeting of the Evangelical Covenant Church in 2009. My application asked, “Where do you want to serve?” and I wrote, “Anywhere God sends me.” So they filled in “Cameroon” for me.

I didn’t even know where Cameroon was. I thought they said, “The Cameroons,” which I thought was a Caribbean Island. And so I went to Cameroon, West Africa. Just before it was time to go, I was told I had to go to France for language training. I was planning to go to one of the two English-speaking zones in Cameroon. I felt ready to go straight to Cameroon.

But I went to France and stayed for four months. I lived in a convent that looked like an old castle with people from 45 countries—nuns, novices, even a bishop. They were all preparing to serve in French-speaking countries around the world.

I had just retired from my job as general manager overseeing 350 Chicago Public School buildings for a company that contracted the maintenance and care of properties for CPS. There was a rhythm in the convent—we went to bed at a certain time, the lights were out at a certain time. After lunch, we paused in silence to rest or take a walk. We could only speak at specific times of the day. Vespers were in held the evening and chapel was twice a day. The first floor of the convent was our gathering area and dining room. We couldn’t have electronic devices above the first floor. The quiet helped me be still. It helped me decompress after that very high-energy job.

In April I arrived in Cameroon. Our Covenant missionaries served in Yaoundé, the capital. I was supposed to be in the northwest region. When I arrived, however, the instructions had gotten mixed up. They thought I was there to be a house parent to missionary kids at Rain Forest International School in Yaoundé. It nearly took an act of Congress to get me up to the northwest region.

In Yaoundé, I started making friends. Cameroonian women taught me how to dress, how to act. They taught me cultural practices, such as not using my left hand to eat. It is a patriarchal society, so if I was standing in line at the bank with four or five other women, any man who came in would be served immediately.

Since it was a French zone, I needed an interpreter to understand the sermons in church each Sunday.

But I recognized the hymns. I started to teach a group of women how to earn an income doing things they wanted to do.

Then the Covenant allowed me to move to the northwest. I had a house there on the compound of the Cameroon Baptist Convention headquarters. I met missionaries and people from all over the world.

My next-door neighbor was from Canada. She introduced me to a young lady named Blessing whom she had helped get her bachelor’s degree. My neighbor paid Blessing a salary to be my assistant. She helped me go out into the villages where people spoke pidgin English to learn about the needs of the people. Blessing acted as a liaison, which allowed me to listen. Often I would sit outside a building while Blessing talked to villagers inside. The buildings in the villages didn’t have glass windows, so I could hear them speaking but I needed her to interpret later. We would compile a list of questions for her to ask them. Then we put their answers into a report of what those women needed. They wanted to raise chickens and goats. Over time, we started a chicken farm. We started a village savings and loan that is still going strong.

I stayed in Cameroon for two and a half years. Then I returned every six months and stayed for six weeks to continue the ministry with the women in the northwest region. I did that until 2016 when war broke out in Cameroon.

Prior to leaving Cameroon, I helped Covenant World Relief & Development organize its 2016 annual meeting in Cameroon. It was like a summit for all the Covenant global partners in Africa and Haiti. Afterward, government officials accused me of bringing in enemies of the state because I helped people from the Democratic Republic of Congo enter Cameroon. The DR Congo was considered an enemy of the Cameroon government. They also questioned why we had hosted people from Haiti who came because they wanted to attend a French-speaking conference. The government threatened me and gave me a short time to leave the country.

Then in 2017, when the conference was held in South Africa, leadership of the ministry to the women of the northwest region was fully transferred over to the Cameroonian women with Blessing as their leader. By that time, she had earned a master’s degree. Now she is finishing her doctorate in public health. Because her country has limited health care, she studied public health to help women take care of themselves and their families.

Pheba was a young girl when I was in Cameroon. Her mother taught in a village school for very little pay. She couldn’t afford to keep both of her children in school, and she felt Pheba had enough education. She wanted to send Pheba’s brother to school instead. I was able to get Pheba into a Christian school and paid for her board and education until she graduated. She is now married and wants to study to be a pharmacist. She has been able to fund two years of school by making and selling bleach, household cleaner, and hand sanitizer. That’s her income.

Before leaving for Cameroon, I had taken a Wilton cake decorating class. I brought my decorating supplies with me and taught Blessing how to decorate cakes. Blessing taught Pheba after I left, so Pheba has also become a caterer. Little things, like going to a Michael’s craft store and taking a cake decorating class, can turn into an enterprise for others.

After I returned from Cameroon, my pastor at Oakdale Covenant Church in Chicago, D. Darrell Griffin, said our church was going send me out to be an urban missionary. They were going to send me to the outermost part of the world. I asked, “Where is that?” And he said, “Mississippi.”

Today I am living in Mississippi. I have to boil our water because it is unsafe to drink it here. I can’t take a shower, flush a toilet, or wash my food. I can’t wash the peaches in my kitchen. This water crisis didn’t just happen overnight. It’s been ongoing. As I have been boiling water for more than a month, I have thought, “Lord, you’ve been preparing me for this.” I already knew how to filter my water, how to carry water to flush my toilet, how to take a shower from a bucket. I had to do all that in Cameroon.

They lived better in the villages of Cameroon than they did here.

After I returned from Cameroon, my pastor at Oakdale Covenant Church in Chicago, D. Darrell Griffin, said our church was going send me out to be an urban missionary. They were going to send me to the outermost part of the world. I asked, “Where is that?” And he said, “Mississippi.”

Today I am living in Mississippi. I have to boil our water because it is unsafe to drink it here. I can’t take a shower, flush a toilet, or wash my food. I can’t wash the peaches in my kitchen. This water crisis didn’t just happen overnight. It’s been ongoing. As I have been boiling water for more than a month, I have thought, “Lord, you’ve been preparing me for this.” I already knew how to filter my water, how to carry water to flush my toilet, how to take a shower from a bucket. I had to do all that in Cameroon.

When I arrived here, I started out working with Big John Perkins at Common Ground Covenant Church in Jackson. A building had been donated to his church, and my job was to get it rehabbed to use for church offices and an after-school tutoring program. There was no barber or beauty shop in that community so we started that too. We started a lawn care business where people who had been incarcerated could get a job.

I found a job with Tougaloo College working with women in the Delta of Mississippi where the mortality rate for infants and women is higher than in some African countries. I could not believe this was the United States of America. They lived better in the villages of Cameroon than they did here. Women did not have prenatal care or healthy nutrition. Babies with asthma, Down’s syndrome. Babies, just a few weeks old, having heart attacks. People had to be brought to Jackson, three hours away, for medical care. It was depressing work.

Needing a change, I interviewed at Galloway United Methodist Church, and I am now the mission and outreach director for one of the largest Methodist churches in Mississippi. I’m in downtown Jackson, across from the Capitol, and on the other side is the governor’s mansion.

One of my main ministries is called Grace Place. Four days a week we feed 80-100 people who are living on the streets or on the margins. As the director, I seek funding. My job is also to find volunteers to work outside the walls of the church. I have found that the church is often generous with their resources but not always with their time.

Grace Place is just one of 16 ministries under my umbrella. Others, like Habitat for Humanity, need people to help us with construction. Meals on Wheels volunteers cook food in their homes and deliver it to the homebound.

We just started a bicycle ministry to help people get to work. The bus service shuts down early in the evening here and doesn’t run on the weekends. If you work a minimum wage job, you can’t get there if you don’t have a car. When a journalist interviewed me on TV about a $1,500 matching grant we had received for this ministry, the local bike shop donated another $1,000. The owner has trained volunteers to maintain bikes, and we have now helped seven people “earn” a bike. They work with us for a total of ten hours—cleaning tables, taking out the garbage, working in the kitchen at Grace Place. As they work, we are building relationship. If they need a repair on their bike, they can come back to us.

I was in Birmingham, Alabama, for a conference and I saw a bicycle fix-it station, where cyclists could come fill up their tires or make simple repairs. Our next goal is to create a similar station where bikers can find everything they need tethered in one space.

Since moving to Mississippi in March 2017, I have become a spiritual director and I went to a Methodist lay ministers’ school. Churches in rural areas here may have anywhere from six to 20 members, and a pastor might serve three to four churches. I’m not a minister, but I serve as a lay minister, which means I can give some of those pastors a much needed break. They contact their district office when they need help, and I am sent to go preach on a Sunday or teach Sunday school classes.

I go back and forth to Chicago often. Pastor Griffin and my church are very supportive. I serve on the Covenant World Relief and Development board. And the last two years I’ve taught a class at North Park Theological Seminary in spiritual direction.

I was called by the Holy Spirit to do the work I’m doing. I haven’t heard him tell me to stop.