Illustration by Mia Larson

A Look at the Impact of Warner Sallman’s Son of Man One Hundred Years After It Appeared on the Cover of the Companion

One hundred years ago, Chicago illustrator Warner Sallman woke up in the middle of the night with a vision from God. He jumped out of bed and sketched out a face of Jesus that he believed was divinely inspired.

He had no idea the legacy that would unfold from that moment. The charcoal drawing became the cover of the Covenant Companion in February 1924. Sallman, a child of Scandinavian immigrants who attended Edgewater Covenant Church in Chicago, was the art director of the fledgling denominational magazine. His idea to illustrate the theme “the Christian life” was to portray Jesus, but he’d been struggling, unhappy with his efforts until the middle-of-the-night inspiration.

The rendering, titled Son of Man, resonated with readers. People asked for reprints, and once all 7,000 copies of the magazine had been sold, Sallman himself paid to reproduce another 1,000 copies. Over the years, he delivered hundreds of gospel-focused “chalk talks,” leaving behind portraits of Christ in churches all across the country.

In 1940 the graduating class of North Park Theological Seminary commissioned Sallman to paint a color version of the image. When two publishers of Sunday school curriculum saw the new version, titled Head of Christ, in Sallman’s home, they were convinced it would inspire Christians everywhere. So Sallman sold them the rights and painted another version for North Park.

Not long after that, the US entered World War II, and tens of thousands of pocket-sized reproductions of Head of Christ were distributed to hospitals and service members who were sent overseas. The image has appeared on greeting cards, church bulletins, clocks, lamps, buttons, funeral announcements, and other printed items.

A 1994 New York Times article claimed that Sallman’s depiction of Jesus was more recognized than Andy Warhol’s soup cans. Covenanter Jack Lundbom wrote a biography titled Master Painter: Warner E. Sallman. Yale University published a critical analysis of his art and its influence, as well as its impact on American evangelicalism in the 20th century. Some said Head of Christ drew Catholics and Protestants together, uniting Americans against the threat of communism at home and abroad. Today Amazon.com sells a 1,000-piece jigsaw puzzle of the image, a King James Version of the Bible illustrated with 28 full-color plates of Sallman’s work, and many similar posters.

Sallman had studied commercial art at the Art Institute of Chicago, and his day job was in advertising. That training may have contributed to the way he painted Jesus. Some scholars have noted the similarities between Head of Christ and the “Breck girl” in shampoo ads of that era. Many people appreciated Sallman’s Jesus because he appeared to be accessible and intimate. It would have been easy for mid-century Mission Friends to recognize the embodiment of Covenant pastor and hymnwriter Nils Frykman’s refrain, “O hallelujah, he’s my friend! He guides me to the journey’s end; he walks beside me all the way and will bestow a crown some day” (“I Have a Friend Who Loveth Me,” The Covenant Hymnal: A Worshipbook, #489).

“For many people it was a devotional experience to see Sallman’s Jesus. He was relatable as a real person,” says LeRoy Carlson, retired Covenant pastor and founder of the Warner E. Sallman Art Collection, Inc. “Head of Christ has gone around the world. It’s been said that the image has been reproduced a billion times. A previous generation knew it very well.”

Sallman would visit churches, set up his easel, and say to his wife and the congregation, “Sing to me about Jesus.” The people would sing and he would paint, Carlson says.

The Covenant was still mostly an ethnic enclave at that point. While the Companion was primarily published in English by 1936, Covenant ordinands had to prove their ability to preach in Swedish well into the 1950s. The era was a turning point for the denomination, marking the end of the century of migration and the emergence of second- and third-generation Swedish Americans. Just as those younger generations were becoming more “American” than “Swedish” and the Covenant was beginning to open up to expanded cultural pluralism, Sallman presented a Christ who preserved a specific ethnic and racial identity. As the Head of Christ became ubiquitous throughout the 20th century, it was sometimes referred to as the “Swedish Jesus.”

Sallman painted his first mural, The Ascension of Christ, in 1926 for the Covenant church in South Bend, Indiana, then known as the Swedish Evangelical Mission Covenant Church. The image depicts Jesus rising into the air in view of his disciples. When the church decided to change locations, it focused its architectural plans around Sallman’s mural, which is currently located in the church narthex and is clearly visible from the street.

A version of the Head of Christ hangs in the library of Northwest Covenant Church in Mount Prospect, Illinois, with a personalized inscription from the artist. Covenant churches across the country have original Sallman paintings in their sanctuaries and basements. Some are discerning how to honor the art and at the same time recognize that as a denomination we are a multiethnic mosaic today.

“Many recognized that this Christ was not an authentic depiction of Jesus, but they did not care,” write Edward J. Blum and Paul Harvey in The Color of Christ: The Son of God and the Saga of Race in America. “‘I know Jesus probably doesn’t look like the picture,’ one claimed. ‘It doesn’t matter. I thank Mr. Sallman for giving me this image to hang onto.’”

What began as one man’s representation of the Son of God to illustrate a magazine cover wound up constricting the imaginations of millions to a Jesus who reflected a white American identity.

“We must acknowledge the fallout of making images of God. No matter how you do that, it can cause damage and pain and division,” Bryan Murphy, superintendent of the Pacific Southwest Conference, said recently in a phone interview. “If we can’t acknowledge the pain caused by that image, we’re not telling the full story. We need to acknowledge both the benefit and the pain that came from it. If we hope to move forward as a true mosaic in the denomination and in the body of Christ, learning from our past is going to be a vital part of our journey.”

Dominique Gilliard, director of racial righteousness and reconciliation for the Covenant, adds that Sallman’s image played a pivotal role in globally canonizing Jesus as white. “Sallman’s Head of Christ has confined, constricted, and restricted what Dr. Willie James Jennings calls ‘the Christian imagination.’ This rendering of a Scandinavian Christ—despite Sallman’s noblest of intentions—has been weaponized by some to embolden declarations of white supremacy, and more recently Christian nationalism,” he says.

Numerous studies document the explicit connection between white Jesus and white Christian nationalism, including American Idolatry: How Christian Nationalism Betrays the Gospel and Threatens the Church, by Andrew Whitehead, and The Religion of Whiteness: How Racism Distorts Christian Faith, by sociologist and Covenanter Michael Emerson and Glenn E. Bracey (to be published in April).

“While this venerated image endeared many Europeans, it simultaneously served as a monumental stumbling block for many non-white Christians globally,” Gilliard continues. “To this day, many people associate this image with colonization, exclusion, and internalized racism. It is really important for the Church—particularly the Evangelical Covenant Church—to soberly reckon with the impact of this renowned painting.”

Growing up in Texas as a Korean American woman in the 1980s and ’90s, Stephanie Ahn Mathis says she rarely saw anyone who looked like her represented in public images. “That internalized the lies that I had less value, dignity, and worth,” she says. “When I began following Jesus, those lies were reinforced through images of a white Jesus that communicated that God is a white man who rules both heaven and earth. This indirectly affirmed the messages of who has access to power, who is called and gifted to lead, and who is not.”

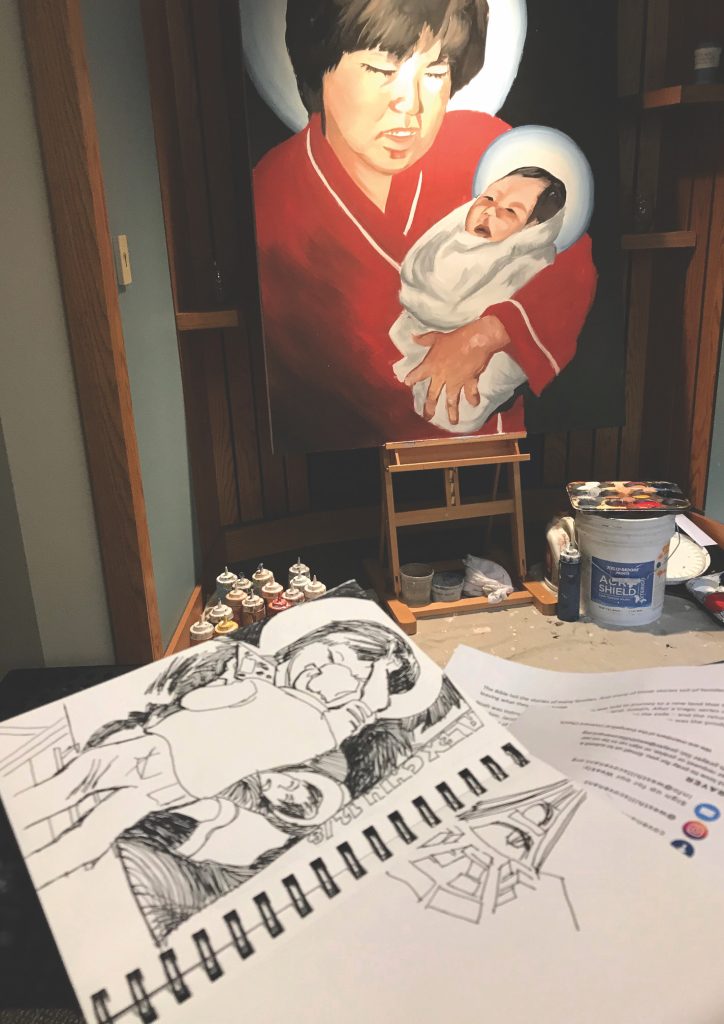

Mathis, who serves as co-senior pastor of West Hills Covenant Church in Portland, Oregon, says their congregation commissioned well-known Chinese American artist Alex Chiu to paint a variety of images of the birth narrative for their worship space (Brown Baby Jesus, Japanese Madonna and Jesus, Black Elizabeth and Mary). “Seeing a brown Jesus in church offers not just a historically and theologically accurate image for us but brings a ‘great reversal’ of the hope and healing of a God who brings good news to the poor, hears the cries of the captives, and is in solidarity with those who are marginalized,” Mathis says. “And each time, I see and feel something move deep in our community, especially our people of color, that we, too, are made in the image of God—what I feel is liberation, love, belonging, and expansive worship.”

When Resurrection Covenant Church relaunched as a 126-year-old church plant several years ago, they considered what to do about the stained-glass window at the front of their sanctuary. Located in the Lakeview neighborhood of Chicago, the congregation is committed to engaging its community, seeking God’s glory and neighbor’s good, and they wanted everyone who came through the doors to feel welcomed and seen. But they knew the art depicting a white-skinned Jesus knocking on a door at the center of the chancel might communicate a different message.

“You can’t just rip the stained glass out,” says David Bjorlin, pastor of worship and creative arts at the church. “That’s cost prohibitive, and it’s also kind of an erasure—to act as if that wasn’t part of our history.” So now an array of images of Jesus surrounds the stained glass. One is Black. Another is Asian, painted by the artist He Qi. One, created by the Franciscan iconographer Robert Lentz, portrays a brown-skinned Jesus holding barbed wire. “I always pictured that as ‘detained Jesus,’ or Jesus in the concentration camp. Then I read that it could go both ways—it’s also Jesus looking at us as the ones behind barbed wire, the ones inside,” Bjorlin says.

Christian attitudes toward art have been complicated throughout history. The ancient Israelites were forbidden to fashion graven images: “You shall not make for yourself a carved image—any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth” (Exodus 20:4, NKJV). It was God who was to be worshiped, not his image. “I’ve developed a deeper appreciation of that Scripture. Whenever we have images that depict God, there are unintended (or intended) consequences!” Bryan Murphy said.

Early Christian iconoclasts feared that images of Jesus could make him too familiar, that overemphasizing his humanity could lead to the heresy that Jesus was just a man, not God. Eventually the Church established formal creeds to help navigate the delicate balance that he was both fully human and fully divine. He was “begotten, not made, of one substance with the father” “true God from true God,” says the Nicene Creed. The Council of Chalcedon stated that Jesus was made up of two distinct but inseparable natures—both human and divine.

“Iconoclasm, the rejection of religious images, comes from somewhere—when we forget that images are pointers, windows that you see through to something else,” says Bjorlin, who is also assistant professor of worship at North Park Theological Seminary. “If they become the place where your vision stops, that’s where you get the reaction against it.”

On the other hand, a sacramental imagination can make way for art and icons to communicate God to us. “James White, the liturgist, talks about the Word being God’s love made audible and the sacraments being God’s love made visible and tangible. So art is a way in which, through your senses, God is communicating Godself to us, through beauty, through wonder, through prophetically challenging images,” Bjorlin adds. “If God doesn’t work through our senses, what does God work through? If we bypass that, it’s as if we’re saying bodies don’t matter. Then we can slip into a Gnosticism or dualism. Part of the sacramental imagination is the belief that beauty helps us draw closer to God.”

He continues, “You’re going to be impoverished if you only have one image. We want to move forward in a way that helps other people see Christ differently.”

In the end, dismantling our preconceived assumptions about what Jesus looked like is difficult work. Yet engaging in that work allows us to better reflect the beautifully complex image of God.