What happened when I asked an image generator for a Jesus in the 21st century.

When figuring out if, when, or how to depict Jesus in any visual art form, there are a lot of issues to consider. Who is the audience? What cultural lenses might people be viewing it through? How do we consider our own understanding of Jesus as a religious, historical, and political figure? And how do others, both in our communities and beyond, differ in their understanding of who Jesus was and is?

That’s all assuming that you’ve made peace with the idea of depicting Jesus at all. Throughout history, the church has grappled with the question of where the line is drawn between iconography and idolatry. Some demur from creating any kind of image of Jesus at all on the grounds that, as Emporer Leo III asserted in the eighth century, icons of our Savior are inherently idolatrous. Of course, even for those who become iconoclasts (a word that means “image destroyer”), it’s worth considering both the history and the practical uses of icons—and here I’m referring to the postmodern usage of the word.

First, people rarely gaze intently at the icons on their home screen. Those images are more like visual shorthand. (“Wow, look at the pixels on that corporate logo, they’re absolutely breathtaking,” said no one, ever.) Like those tiny images on our phones, icons exist not for their own sake, but to point to something greater. When we tap the icon for Waze or Google Maps, we do so not because of the inherent aesthetic quality of the icon on the screen, but because we want to avail ourselves of mapping functionality to locate ourselves within the world.

That’s not to say that the aesthetics of smartphone icons don’t matter. They matter a lot. Corporations spend good money paying graphic designers and branding consultants to help them create just the right tiny image to represent their product or company. But in this context, aesthetics matter only to the extent that they compel users to engage with the product.

Religious icons do something similar.

When we look at a visual illustration of Jesus, most of us do not assume that what we’re looking at is a faithful recreation of the physical characteristics of the historical figure Jesus of Nazareth. We would no more assume that any single image of Jesus is technically accurate than we would assume that a pop song about romantic love provides a coherent account of events in the relational history of a specific couple. (“You call that a love song? Where is the part where they sign the copious pages of paperwork needed to close on a house?”)

Instead, images of Jesus are usually intended to encourage, inspire, comfort, or evoke wonder. Notable works of art, including those depicting Jesus, are venerated not only because of the value of the subject but because they stir up our emotions. Art can communicate truth in ways that sometimes words cannot.

An artistic rendering of Jesus should compel us to engage with Jesus.

So an artistic rendering of Jesus should compel us, not simply to assent to his existence or politely recite trite spiritual bromides, but to engage with Jesus. The most arresting portraits of Jesus use my knowledge and understanding of who Jesus was to ignite my imagination of who Jesus might be right now, today. We crave such holy imagination because it helps us make sense of the world.

Not only that but the artistic renderings of Jesus that I long for help answer another even more important question: Where is he taking us?

Having looked back at historical depictions of Jesus, I’d like to speculate on what the future might portend.

Any discussion about the future of art, cinema, music, or culture today must include a reckoning with the arrival of artificial intelligence. Unlike previous iterations, today’s AI tools are generative; they use machine learning to form neural networks that mimic the way human brains operate. They are fed thousands or even millions of actual artworks from human artists, and then they use what they’ve learned to generate new works of art.

The thing to remember here is that neural network-driven AIs regurgitate the stylistic choices of human artists in response to prompts from the user. So in a sense, when an AI is asked to create an image of Jesus, it’s only doing what we as humans have learned to do, both individually and collectively. It surveys the catalog of spiritual, historical, and artistic ideas connected to Jesus to which it has been exposed and synthesizes those data points into new artistic work. It just does it a lot faster—and without much nuance.

That these tools have reached a functional existence is both scary and exciting; their promise of unfettered productivity seems limitless, but at what cost? The unintended consequences could prove to be calamitous.

Recently I took some time to experiment with the free AI-based image generator Stable Diffusion Online, which works by responding to a text prompt. If you input the prompt, “cute little bunnies surrounding a majestic unicorn wearing headphones,” it will do its best to spit out an image matching that description. Unfortunately, AIs like this have difficulty with colloquialisms, sarcasm, and figurative language, so they might not be able to tell the difference between the phrases “You’re an artistic masterpiece” and “You’re a real piece of work.”

The following is a selection of results I got from a variety of prompts involving Jesus.

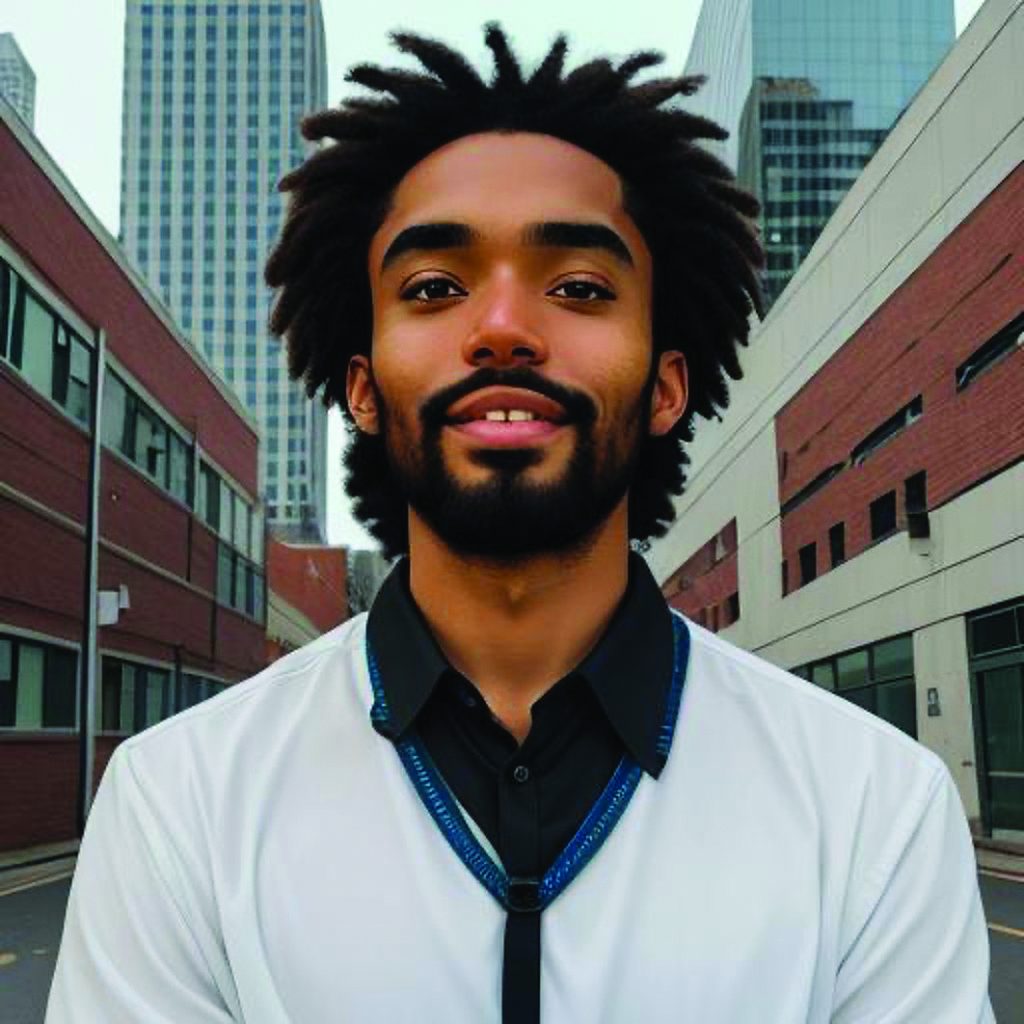

prompt one:

Urban multiethnic Jesus in a 21st-century work setting

In the first prompt, apparently the AI is reflecting the stereotype that “urban” is coded language for “black,” which is why it reverted to a lighter-skinned picture when I used “suburban” in the second prompt.

prompt two:

Suburban multiethnic Jesus in a 21st-century work setting

Figuring that it might not know what to do with the word “multiethnic,” I thought I’d get a little more specific.

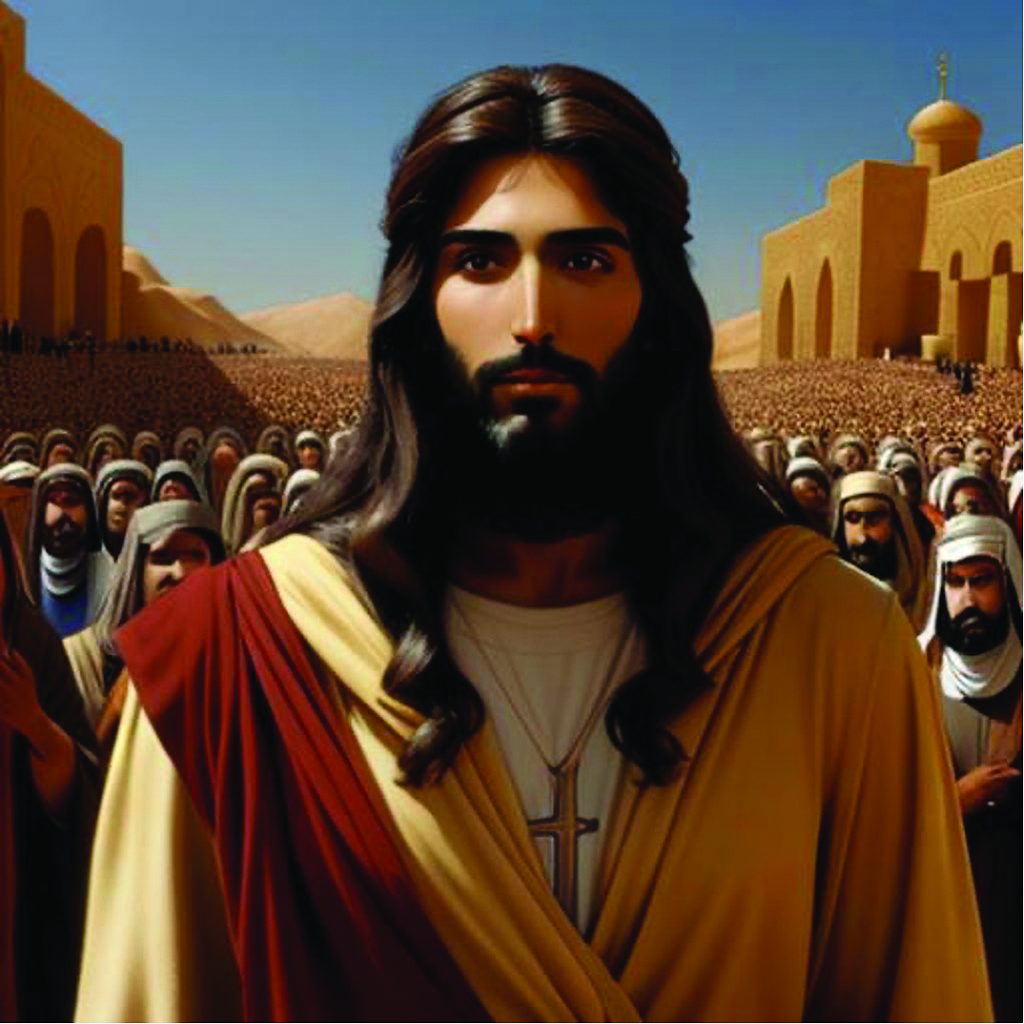

prompt three:

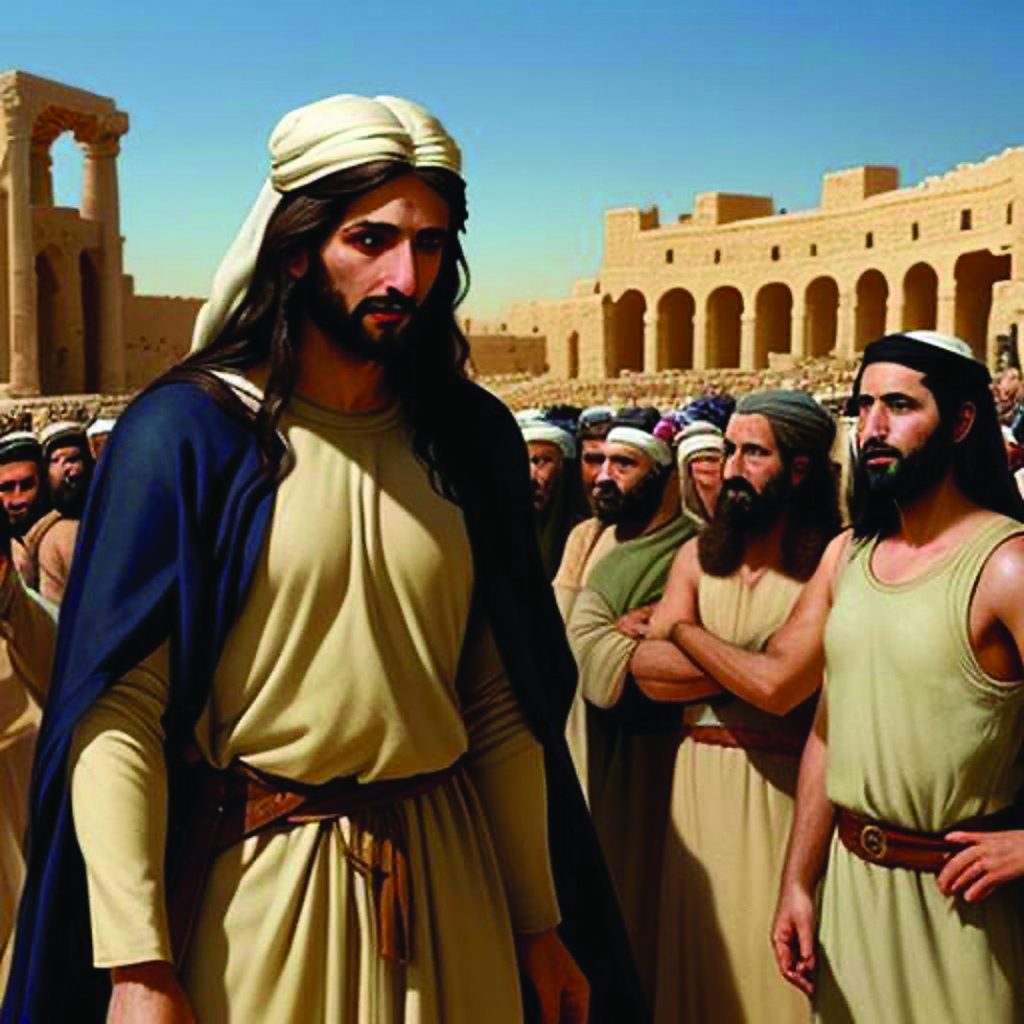

Historically accurate Middle Eastern Jesus in the first century

So far, so good, right? Except…wait…what’s that below his neck? Oh no, that will never do. Jesus wouldn’t have worn a cross. That’s an obvious anachronism.

I tried again and added a negative prompt, which tells the AI what not to include.

prompt four:

Historically accurate Middle Eastern Jesus in the first century (no cross necklace)

So there’s no cross necklace, which is good, but what’s with the hair? Is Jesus auditioning to play an 18th-century British aristocrat? Also, what’s going on with the guys in the background? Are those headbands? It looks like the one on the far right is wearing a yarmulke. I know Jesus was Jewish, but that seems like another anachronism.

Since it’s having problems sticking to the historical period of Jesus’s life, let’s go back to something more contemporary.

prompt five:

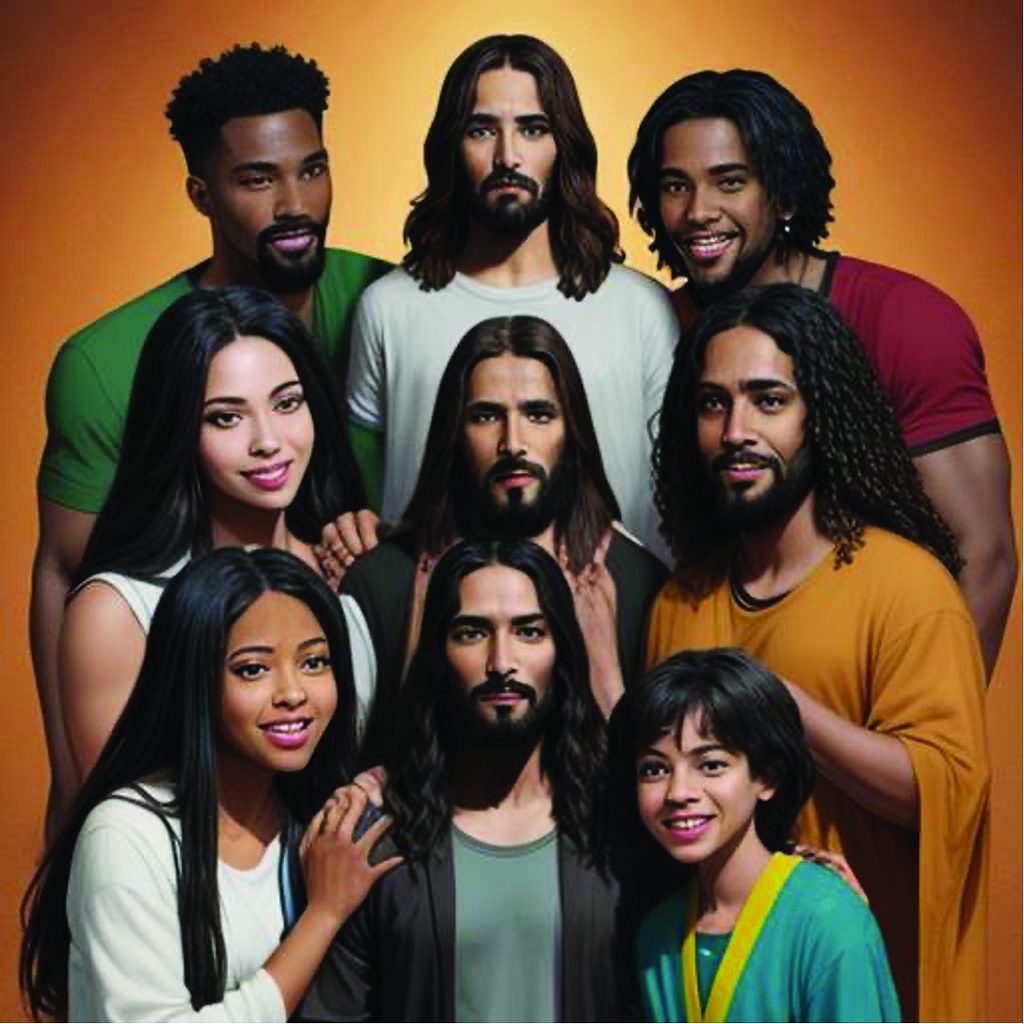

21st-century Jesus, multiethnic

It seems the AI has gone with a more-is-obviously-better approach. It’s as if this portrait was designed by committee. “Who said we only need one Jesus? Let’s have multiple Jesuses. And let’s do the Benetton thing where we include a bunch of people from different ethnic backgrounds. And some women, and heck, throw in a kid too!” It reminds me of all the hacky jokes still circulating on the internet showing proof that Jesus belongs to different ethnicities.

At this point, I’m afraid to try anything further. If I input, “Jesus flipping over the tables,” it might show me a picture of Jesus captured in midair doing an acrobatic somersault.

The idea of using AI to render pictures of Jesus could be entertaining, but it’s hard to overlook the downsides.

First, for these tools to be accepted as ethically permissible, the issue of plagiarism must be resolved. (It’s worth mentioning that we have discerned that publishing these images here is permissible under the Fair Use doctrine because they illustrate commentary and analysis.)

Regardless of the end result, however, there’s also the issue of source material. As it stands now, multiple AI research companies are fending off lawsuits from artists and authors upset that their work was used to train AIs without any sort of compensation. This issue could be mitigated if future regulatory frameworks require AI firms to seek permission from creators and compensate them for their training data. Maybe the AIs could be trained to cite their sources, assigning percentage values to track which artists or artistic works were most influential in their generative outputs.

In addition, the advent of AI in art presents an even greater existential threat to artists, which is to devalue artistic creation itself. There’s a real temptation for users to employ AI tools to generate art assets that contribute to other creative works, such as album art for a piece of music or background art in a video game. Not only that, but such tools artificially suppress artistic demand across the board. Who would pay $500 for a painting by a human artist, or even $50 for a licensed reprint, if AI can create a similar work for $5?

We cannot continue to experience art that reflects the beauty, complexity, and frailty of the human experience if we habitually outsource our creative processes to inhuman tools.

Even for human visual artists who want to use AI as part of their industrial toolkit, to what extent can it still be considered creativity if you’re just creating text prompts for computers to interpret? More to the point, if these tools proliferate, how will artists continue to learn how to sharpen their craft? We cannot continue to experience art that reflects the beauty, complexity, and frailty of the human experience if we habitually outsource our creative processes to inhuman tools.

Still, it’s undeniable that this technology isn’t going away, and if we can manage to mitigate some of the potential harms, AI art could be used for good. Such tools could be cost-effective solutions for smaller churches or organizations in smaller applications where it might not be feasible to commission a visual artist or purchase a licensed reproduction.

As the author concludes in Hebrews 13:8, Jesus Christ is the same yesterday, today, and tomorrow. As we continually march into tomorrow, let us avoid the extremes. Let us not be so enamored with innovative technology that we embrace it blindly and uncritically. And let us not be so afflicted with fear that we refuse to use tools at our disposal to do the work to which we’ve been called.

More than anything else, let us put these icons to work to point us back to Jesus as the author of our faith, the sustainer of our work, and the architect of our future.